People are different. We can use our differences as an opportunity to share and learn or we can use our differences as an excuse to build walls between us. When we highlight differences between groups of people to increase suspicion of them, to insult them or to exclude them, we are going down a path known as “othering.”

Us vs. Them: The process of othering

By Clint Curle

Published: January 24, 2020

Tags:

Photo: USHMM photo 37295

Story text

Paul Herczeg remembers the precise moment he was made to feel fundamentally different. It happened in 1944, shortly after the Nazis invaded his home country of Hungary.

“It didn’t take very long before the edict came out – every Jew must wear a yellow star. This is the first time I realized that I’m different, even among my friends.”

— Holocaust survivor Paul Herczeg

The Nazis used the yellow star to identify Jews as separate and inferior. Herczeg’s sense of being suddenly set apart as “different” is a result of the process of othering.

The process of othering

The process of othering can be divided into two steps:

- Categorizing a group of people according to perceived differences, such as ethnicity, skin colour, religion, gender or sexual orientation.

- Identifying that group as inferior and using an “us vs. them” mentality to alienate the group.

Othering involves zeroing in on a difference and using that difference to dismantle a sense of similarity or connectedness between people. Othering sets the stage for discrimination or persecution by reducing empathy and preventing genuine dialogue. Taken to an extreme, othering can result in one group of people denying that another group is even human.

Othering and the Holocaust

An extreme example of othering and its consequences is found in the Holocaust – the systematic persecution and murder of six million Jews organized by Nazi Germany and its collaborators from 1933 to 1945.

In addition to committing genocide against the Jews, the Nazis committed genocide against the Roma and the Sinti. Many other groups, including people with disabilities, homosexual men, Slavic peoples, political opponents and Jehovah’s Witnesses were also violently persecuted during this period.

German soldiers round up Jewish prisoners at gunpoint during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in 1943.

Photo: USHMM photo 26543The Nazi party divided humans into two categories: the so‐called “Aryans” (the Germanic people) whom they considered genetically superior; and the so‐called “inferior races” composed of Jews, along with Slavs, Roma and Sinti, and Blacks. This ranking of some groups of people as “lesser than” was a process of othering that helped create the conditions for the genocide.

Hungarian Jews forced to wear yellow stars.

Photo: Yevgeny Khaldeï, Fortepan photo 58305Paul Herczeg’s story

Paul Herczeg lived through this experience of othering. He was born in 1930 in Újpest, Hungary. His parents were proud Hungarians and traditional Jews. Like many young people around him, Paul joined the Jewish Boy Scouts Association and participated in many sports and cultural activities at school.

When Nazi Germany invaded Hungary in March 1944, Paul and his family were forced to wear a yellow star. Later that year, they were forced to move into the Újpest ghetto. In July 1944, Paul and his parents were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Paul’s mother was murdered in Auschwitz, but he and his father were spared and transported to a small camp near Mühldorf, Germany to work as slave labourers. His father died from overwork and starvation.

Paul was sent to work in the camp kitchen, and he credits the heating in the building and the potato peels he hid under his clothes for saving his life.

Video: Paul Herczeg Human Rights Tool

The violence and suffering inflicted on Paul, his family, and the millions of other victims of the Nazis were enabled by the psychological and social power of othering.

Learn more:

Teaching resources: Holocaust

A Yiddish poem from the Holocaust

The stain of antisemitism in Canada

Othering and the Rohingya genocide

The process of othering plays an important part in many other human rights violations, such as the recent genocide of the Rohingya in Myanmar.

The Rohingya are a mostly Muslim minority that make up one‐third of the population in a region of Myanmar called Rakhine State. Although they have been in the region since the 15th century, Rohingya continue to be viewed by the Buddhist majority of Rakhine state as “Bengali immigrants”. This labelling is an example of the othering process that denies the Rohingya their status as fellow citizens.

Since the early 1980s, government policies have stripped Rohingya of citizenship and enforced a system where they were first isolated and marginalized and then targeted for genocide.

Refugee camp for displaced Rohingya people.

Photo: DFID MyanmarIn 2012, violence broke out in Rakhine state, killing hundreds and displacing thousands of Rohingya. After an attack on a border post in 2016, in which police officers were killed by Rohingya fighters, Myanmar’s military launched a crackdown. The military action, consisting of a wave of village burnings, murders and rapes, forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. Violence against Rohingya has escalated since then, leading to the acknowledgement of genocide‐like crimes by the United Nations and the Canadian government in 2018.

Yasmin Ullah’s story

Yasmin Ullah, a Rohingya Canadian, was born in 1992 to Rohingya parents in Buthidaung, Myanmar. When she was three years old, Yasmin was forced to flee Myanmar with her parents due to the increasing hate, persecutions, and human rights violations that the Rohingya of Myanmar experienced.

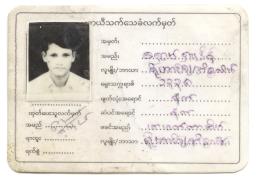

In Thailand, Yasmin and her family were stateless, meaning they did not have the protection of any kind of national citizenship, and faced constant threats of deportation. Yasmin remembers how her grandmother’s citizenship document was taken away from her and she was given a different card which identified her not as a Myanmar citizen, but as Bengali Muslim. This process of being denied citizenship and being singled out as different is another form of othering.

Temporary registration cards were issued to Rohingya after a new citizenship law was passed in 1982. The cards stated that Rohingya were not full citizens of Myanmar.

Photo: CMHR, Aaron CohenWhen Yasmin was 19 years old, her father met two Canadian missionaries who had heard him speaking about the persecution of the Rohingya. They offered to help him come to Canada with his family. There were many obstacles to this process because the family was stateless, but they finally acquired exit permits and came to Canada as refugees in 2011.

Video: Yasmin Ullah Human Rights Tool

If you are deemed different, or your culture is different, you are pushed aside. You are deemed unworthy. You are deemed unimportant to talk to.

Learn more:

Time to Act: Rohingya Voices

Rohingya women call for justice

Resource guide: Rohingya

How can we recognize othering?

Othering can be done by governments, as in the case of the Nazis forcing Jews to wear yellow stars or Myanmar declaring Rohingya to be non‐citizens. Not all othering is obviously violent or repressive, though.

Long before the Nazi government passed laws officially targeting Jews, they used propaganda to spread false and insulting antisemitic stereotypes about Jews. The circulation of hateful and divisive ideas is a kind of social othering that can set the stage for more violent acts.

This kind of othering can also take place in popular culture, everyday conversation, and online interactions. Othering is at work when people use images and words that distort, insult, exclude, or dismiss another group of people. It can take the form of jokes or insults that can be hurtful and isolating, setting some people apart as inferior or different. Othering can also be seen when people reject ideas they disagree with by resorting to stereotypes that insult or attack the people who express them.

If these othering opinions spread unchallenged, they are more likely to be accepted as normal or true. And then it becomes easier for governments and other groups to enact repressive laws or take violent action against the people who have been othered.

This is why it is so important to recognize and resist othering in all its forms.

Why does othering happen?

The process of othering can happen for many reasons. When times are tough because of economic, political, or environmental problems, people sometimes look for someone to blame. They are more likely to target groups with little power or who have been oppressed in the past by the effects of othering.

Also, people often try to make sense of our confusing and constantly changing world by relying on oversimplified or outdated ideas about history or about differences between groups of people. When these ideas involve prejudiced generalizations, they can contribute to othering.

People sometimes use othering to make themselves feel more secure or powerful. This is most obvious when leaders try to drum up support by using othering to attack their opponents or groups of people they want to turn into an enemy. But this can also happen in everyday life when people use insults or exclusion to make themselves feel better at the expense of others.

Othering at work around us

The process of othering can be seen in many different situations. Paul and Yasmin lived through extreme events. But othering happens in smaller ways too. It is important to understand that if we highlight a person's differences, we risk treating that person differently.

Almost all human rights violations are rooted in othering. Understanding and identifying the process of othering are important first steps in stopping them.

Can you look at your own life and see othering at work?

This story draws on and is intended to support the “Us vs. Them – Creating the Other” learning resources co‐developed by the Canadian Museum for Human Rights and the Montreal Holocaust Museum.

Ask yourself:

How do I handle discomfort with difference?

Can I think of any groups of people who experience othering in my community or country?

Have I ever felt more powerful by excluding someone?

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Clint Curle. “Us vs. Them: The process of othering.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published January 24, 2020. https://humanrights.ca/story/us-vs-them-process-othering