This release is more than two years old

This release is more than two years old. For additional information, please contact Amanda Gaudes from our Media Relations team.

News release details

A miner’s helmet, a nurse’s uniform, and a railway conductor’s cap are being used to help tell the story of three important labour‐rights struggles that led to positive changes for Canadian workers.

Created in recognition of the 100th anniversary of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, a new exhibit opens today at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR), profiling three stories of organized workers whose fight for rights on the job helped many others.

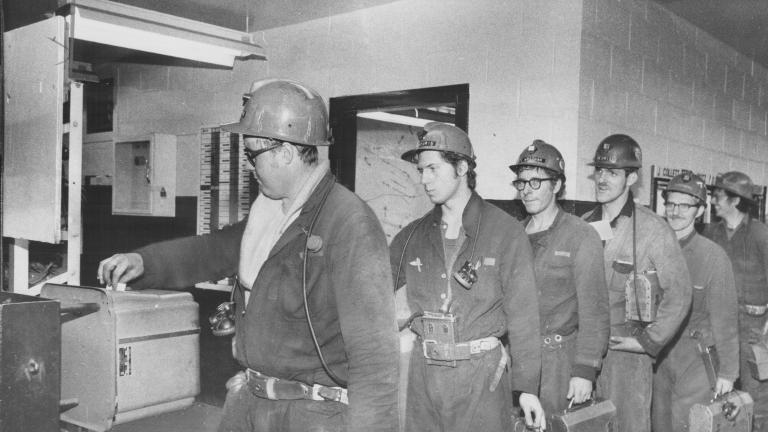

Union members representing uranium miners in Elliot Lake, Ontario found out in 1974 that evidence had been suppressed about linkages between their jobs and high incidences of lung cancer and silicosis – which workers had long suspected. They went on a three‐week wildcat strike that led to a royal commission inquiry. The resulting legal changes became a turning point for workplace health and safety regulations in Canada, including the right to know about hazards in the workplace and the right to refuse dangerous work.

A group of Indigenous nurses also created improvements for others when they organized in 1975 to form what is known today as the Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association (CINA). This organization supports thousands of nurses in a medical profession that has traditionally had little understanding of Indigenous cultural practices. The nurses also work to break down barriers for access to adequate health care for people in Indigenous communities.

Black men working for Canadian railways as sleeping car porters in the early 1900s also organized to improve conditions on the job. Faced with racism that limited their opportunities for employment, many found jobs as porters, a role that was often demeaning and exhausting. Black porters worked long hours, with no job security or chance for promotion, and were expected to act in a servile manner. In 1942, they joined the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and negotiated their first collective agreement for improvements in pay, benefits and working conditions – including time to sleep.

The exhibit, Rights on the Job, runs in the Level 2 “What Are Human Rights?” gallery until October 2020.

-30‐

This release is more than two years old

This release is more than two years old. For additional information, please contact Amanda Gaudes from our Media Relations team.