Grace Acan and Evelyn Amony were abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda when they were just girls. They were enslaved and spent years in captivity, away from their families. They managed to find their way back to freedom but have faced many new struggles since they returned home.

Voices of women and girls enslaved in war

Survivors of the LRA in Uganda speak out on violence, captivity and healing

By Isabelle Masson

Published: June 12, 2019

Tags:

Photo: Erin Baines

Story text

The Museum’s exhibit Ododo Wa: Stories of Girls in War features the stories of Grace and Evelyn, told from their perspectives and in their own voices. Their courage, resilience and spirit in the face of adversity are highlighted through images, text, artifacts, animated films and interviews. “Ododo Wa” means “our stories” in their language, Acholi—a dialect of the Luo‐speaking peoples of Eastern Africa.

We never stopped thinking about coming home.

Women’s and girls’ stories are crucial to understanding what makes and sustains wars. Their experiences reveal important dimensions of conflicts that are too often ignored. While sexual violence is commonly seen as an unfortunate consequence of conflict, it is in fact often a central strategy of war. In Uganda, the LRA waged war against the government for over 20 years, from the mid‐1980s onward. Tens of thousands of children were abducted and forced into the ranks of the rebel army led by military and spiritual leader Joseph Kony. These children received military training and were forced to carry heavy loads of ammunition and other material through bush and mountains, walking for days on end with little food or water. In captivity, they constantly faced violence from both the rebels and the Ugandan army hunting the LRA across northern Uganda and South Sudan. Teenage girls, like Grace and Evelyn, served as soldiers and were forced into conjugal slavery. This meant that they had to serve as wives to LRA commanders and fighters, and were forced to have children with these “bush husbands” to build what Kony saw as a new and pure Acholi nation.

Grace’s story

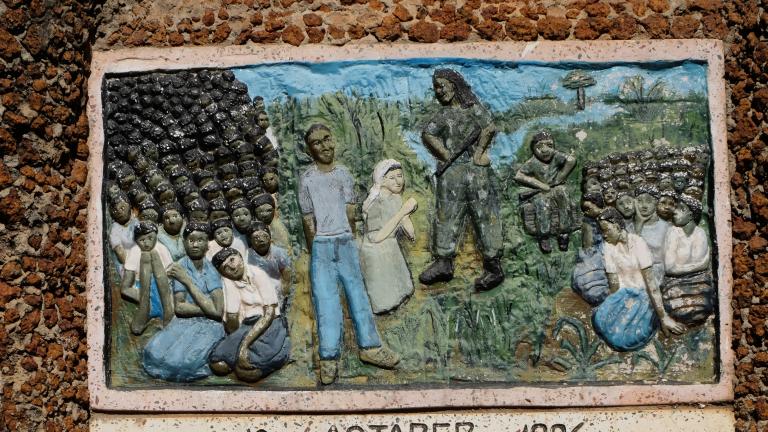

Grace Acan was abducted from St. Mary’s College, an all‐girl Catholic boarding school in Aboke, northern Uganda, at the age of 16. She was among the 139 girls between the age of 13 and 16 kidnapped from one of the school dormitories by rebel soldiers in October 1996. Grace was a determined student, who excelled in science and English. She dreamt of independence and planned on becoming a nurse. In LRA captivity, she was enslaved and told to forget about her studies and family.

In the LRA, they favoured men. There’s that culture, that men are the rulers. They have the power to make a choice or to do what they want. Women had no voice. And this was opposite from what I was growing to be.

Grace was treated with suspicion because of her level of education and ability to speak English. Not only were her freedoms taken from her, Grace was forced to marry a commander old enough to be her father and had two of his children – one of whom was later killed in a military ambush.

Grace spent eight long years in captivity before she was finally able to escape. Her family welcomed her, along with her 14‐month‐old daughter. Grace soon returned to school, but she struggled to reintegrate into her community.

Evelyn’s story

In 1994, 11‐year‐old Evelyn Amony was walking home to her grandmother’s house after school in when she was abducted by a group of LRA soldiers. Evelyn’s grandmother tried to protect her, pleading with the rebels and defying their orders not to cross a line that they drew in the sand. The soldiers would not be deterred and took her grandchild away.

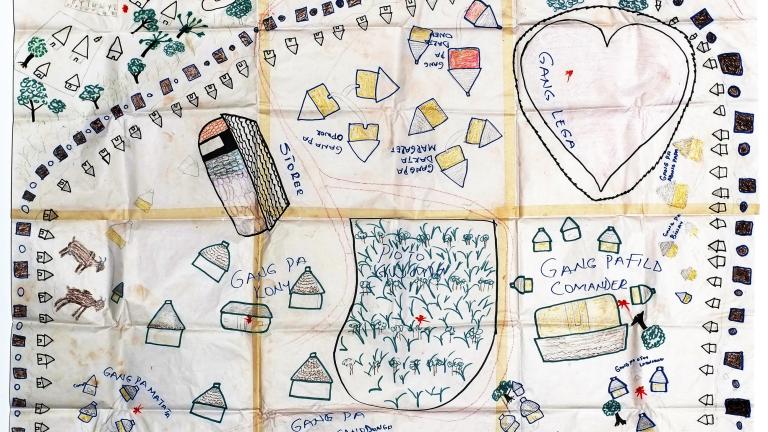

Life in the LRA was organized into “family” units headed by a commander and a senior wife. Evelyn was enslaved and assigned to the LRA leader’s family, to care for two of his children. Kony referred to Evelyn as his “first born,” acting as a father figure to her in the early stage of her captivity. But soon he forced her to become his wife. Evelyn gave birth to the first of three children with him at the age of 14. In 2005, after 11 years in captivity, Evelyn was captured by government soldiers in a military ambush. She and her 10‐day old baby were almost killed. Evelyn was taken to a rehabilitation centre in Gulu with her two surviving children—one of her daughters disappeared in the chaos of another military ambush. Shortly after returning home, she was asked to take part in peace negotiations between the Ugandan government and the LRA.

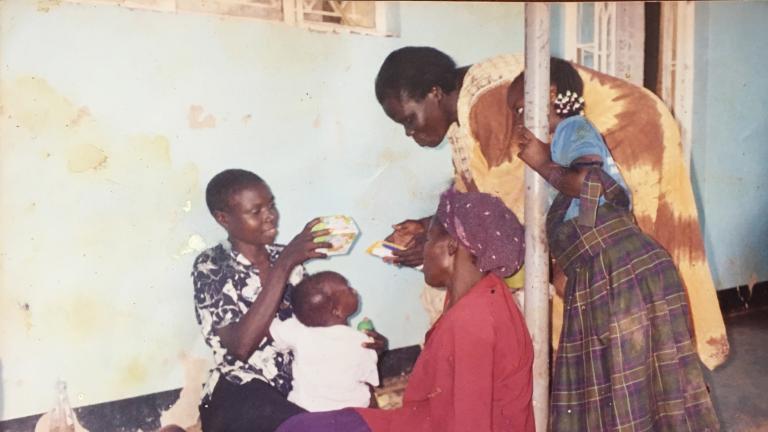

Returning home after captivity

Girls who were abducted by the LRA grew into women while in captivity. When they returned home, many viewed them as rebels, even though they had been taken and held by force. After all they had gone through at the hands of the LRA, young mothers and their children now faced discrimination and poor treatment back in their own communities. With limited education and support, they struggled to rebuild their lives.

When we returned, we had lost almost everything.

Finding their voices

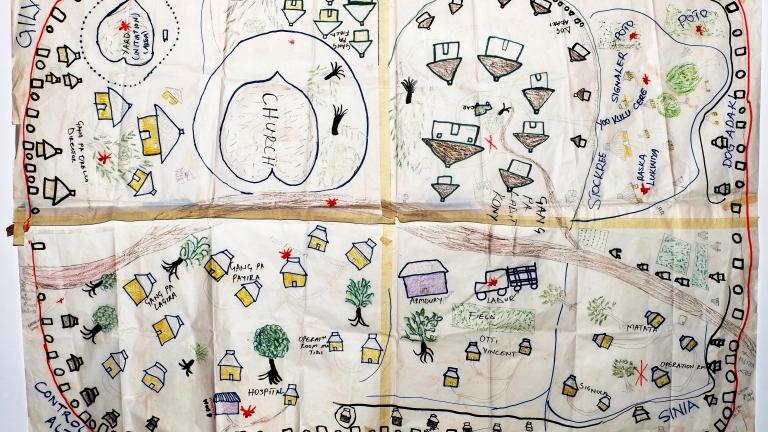

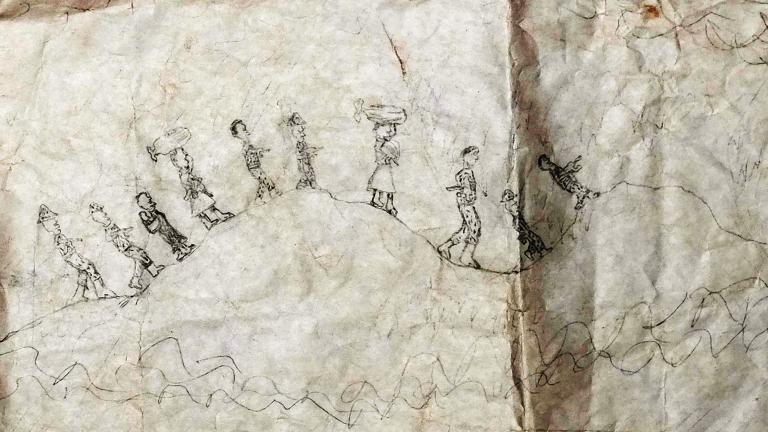

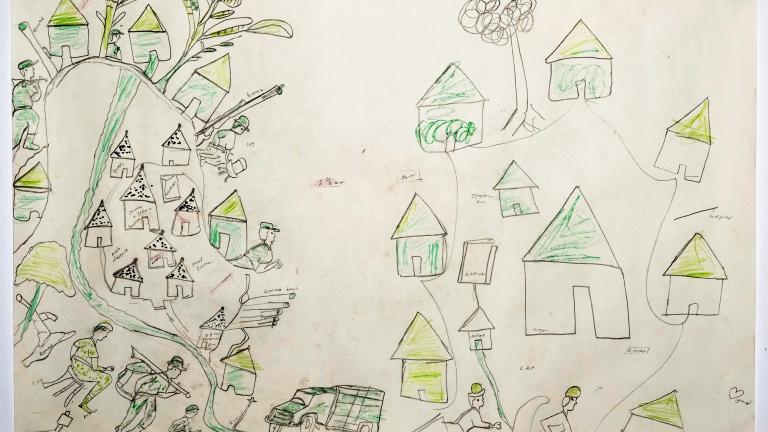

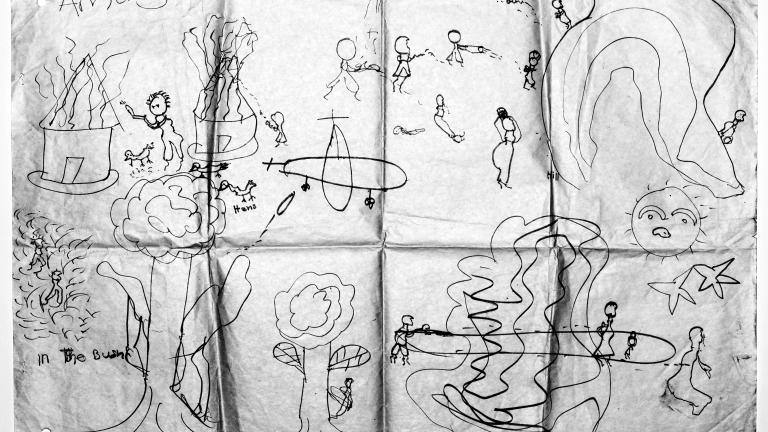

Through different means, such as drawing the places where they had lived in captivity, survivors began to open up about their traumatic experiences. As the women shared their stories with each other, they found healing and a need to speak up about what had happened and how they, and their children, continued to face adversity.

In 2008, Evelyn and Grace co‐founded the Ugandan Women’s Advocacy Network with other survivors. Today, the organization represents 900 women. From their perspectives, justice includes much‐needed reparations for survivors such as access to healthcare, financial compensation, access to land ownership, education, vocational training and the recognition of inheritance rights for children born in captivity.

Many of us have children, so we really need to focus on the stability of our members – their ability to lead better life, look after their children and, of course, hope for the future.

In 2015, Evelyn published her memoir I am Evelyn Amony: Reclaiming My Life from the Lord’s Resistance Army. Grace followed suit in 2017 with her own memoir Not Yet Sunset: A Story of Survival and Perseverance in LRA Captivity.

An exhibit to amplify their voices

The Museum is currently presenting an exhibit about these stories and experiences called Ododo Wa: Stories of Girls in War. “Ododo Wa” was the title of the storytelling initiative of the Ugandan Justice and Reconciliation Project that originally brought Grace, Evelyn and other women together. “Ododo wa” translates as “our stories” but it can also be used to refer to stories or tales told to children.

Ododo Wa: Stories of Girls in War amplifies Grace and Evelyn’s unique voices and perspectives. Our goal in selecting images and artifacts, writing exhibit text and creating films is to let their hopes and dreams, courage, strength, voice and agency shine through. Bright colours and hand‐made drawings evoke these meanings and shape a story that is ultimately one of healing and advocacy for justice.

Animation is used for creative storytelling and to ensure the content is accessible to a wide audience, including younger people. We are pleased to share the first few seconds of a film that is presented in the exhibit. The opening of Grace’s film shows a blue thread forming into a school uniform. The thread is made stronger by other threads, representing the survivors who joined together to form an advocacy organization.

Video: Grace's film (excerpt)

Ododo Wa: Stories of Girls in War has been developed in close collaboration with Grace and Evelyn, and with Conjugal Slavery in War (CSiW), a project that brings together researchers and grassroots advocacy organizations from Canada, the Democratic Republic of Congo, England, Liberia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa and Uganda. CSiW captures a part of history that is far too often overlooked by documenting cases of forced marriage and conjugal slavery in conflict situations. In partnership with CSiW, we hope to tour the exhibit across Uganda and other countries so that it may serve as a catalyst for grassroots community dialogue on the issues of sexual violence in conflict, and justice and reparations for war‐affected women and their children.

Ododo Wa: Stories of Girls in War can be seen in the Rights Today gallery on Level 5 until November 2023.

Ask yourself

How can I take action on the issue of sexual violence in conflict?

What can I learn by paying attention to women’s and girls’ experiences of war?

What does justice for war‐affected girls and women mean?

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Isabelle Masson. “Voices of women and girls enslaved in war.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published June 12, 2019. https://humanrights.ca/story/voices-women-and-girls-enslaved-war

Continue the conversation

This story sparked interesting discussion when we shared it on social media. Follow us on Facebook and X to join the conversation.

annie bunting

X June 19, 2019 by annie buntingAlice Baker

X June 19, 2019 by Alice Bakererin baines

X June 19, 2019 by erin baines