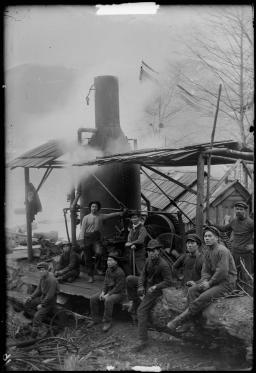

To understand these two policies and the terrible effect they had on generations of individuals, you need to know a little about the history of Chinese immigration to Canada. In the late 1800s, there was an influx of Chinese immigration to Canada’s West. Many came to help build the Canadian Pacific Railway – the first Canadian Railway to cross the Rocky Mountains and reach the Pacific Coast – but Chinese people emigrated for many other reasons, too: working on farms, opening stores and participating in logging operations in British Columbia and elsewhere.

Unfortunately, many white Canadians were hostile to Chinese immigration. In 1885, immediately after construction on the Canadian Pacific Railway was complete, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act, which stipulated that, with almost no exceptions, every person of Chinese origin immigrating to Canada had to pay a fee of $50, called a head tax. No other group in Canadian history has ever been forced to pay a tax based solely on their country of origin. “It was an attempt to basically discriminate against the Chinese,” Dr. Yu explained. “…it was a way to alter the flow of migrants to the new Canada to be weighted towards European and in particular British migrants.”

In 1900, the head tax was raised to $100. Then, three years later, it went up to $500 per person. Between 1885 and 1923, approximately 81,000 Chinese immigrants paid the head tax, contributing millions of dollars to government coffers. One of those who paid the tax was Dr. Yu’s maternal grandfather, Yeung Sing Yew, who immigrated to Canada in 1923. Yeung was also one of the last Chinese immigrants to pay the head tax; in the same year as he arrived in the country, the Canadian government passed a new Chinese Immigration Act, which came to be known as the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Under the new act, Chinese immigration to Canada was completely banned. This legislation was kept in place until 1947, and its effect on Canada’s Chinese community was devastating.

Because of the costly head tax, by 1923, Canada’s Chinese communities were largely “bachelor societies,” where men outnumbered women by a ratio of almost twenty‐eight to one. Many Chinese men had come to Canada alone, hoping to save enough money to bring over their wives and families. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923 destroyed those dreams. Yeung spent many years living alone in Canada.

Even after 1947, immigration to Canada was still challenging. Until Canada’s immigration system was overhauled in 1967, few Chinese were let into the country, and usually only for family reunification purposes. In fact, Yeung first met his daughter – Dr. Yu’s mother – when she immigrated to Canada in 1965. Both of Dr. Yu’s parents worked full time, so when he was young, he spent a lot of time with his grandparents –this brings us back to the long walks to Chinatown.

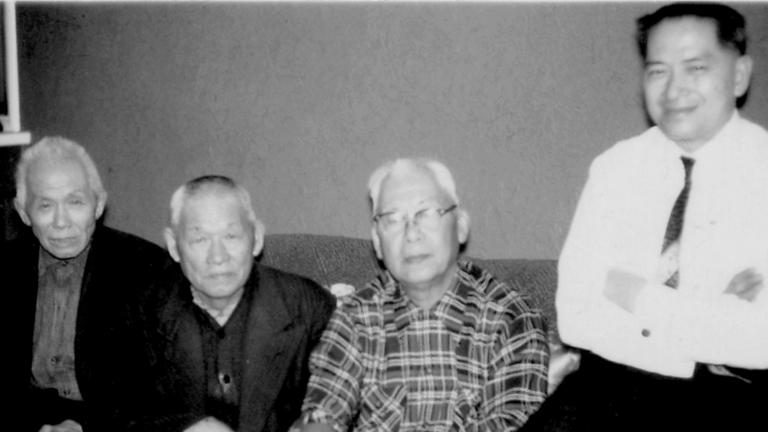

It was only when Dr. Yu was older, and knew his grandfather’s whole story that he finally understood what the long walks were about: they demonstrated his grandfather’s joy at being reunited with his family. “It explains his showing me off to all those other elderly men gathered at these cafes in Chinatown,” Dr. Yu told me. He recounted how excited the old men would be, and how they would enthusiastically congratulate his grandfather: "It explains why my grandfather having me here was like an explosion of joy because the Exclusion Act basically made it impossible for many of them… to marry someone and have kids turn into grandkids. Many of them would die alone literally, growing old alone except for these other men in these cafes."

This experience helped teach Dr. Yu that the effects of racial discrimination take a psychological toll on many generations. He remembers how, until the late 1940s, the Chinese in British Columbia were not allowed to swim in pools with whites, and were segregated in movie theatres. He told me how many Chinese immigrants lived in fear of being deported because authorities would often look for reasons to remove people from the country. Dr. Yu’s grandfather used a fake identity, called a “paper name,” to get into Canada because he did not have a legal birth certificate – something that was very common at the time – and so he worried for many years about the authorities coming for him.

"So my grandfather, you could say he lived a life that unfortunately distorted who he could be, who he was – and by the time I knew him as an elder in the community, he wasn’t the same man he was when he was young. When I learned about things like the head tax…. It explained things about my grandfather that I already felt and knew. It’s kind of interesting that you can feel something’s wrong and not know why until later. You kind of don’t know the words, and then you finally find a name for your pain. You say "Oh now I get it. Now I understand.""

Chinese Canadians did call for acknowledgment of the human rights violations they experienced due to the head tax and Chinese Exclusion Act. In 1983, Dak Leon Mark and Shack Yee requested that the Canadian government refund the $500 head tax they had each paid. In the years that followed, some 4,000 Chinese Canadians came forward seeking redress. Some Chinese Canadians also pursued justice through the court of law. Redress finally came in June 2006, when Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized in the House of Commons. That same year, $20,000 in redress was offered by the Government of Canada to all surviving individuals who had paid the head tax. The government also allocated $24 million for a community historical recognition program and $10 million for a national historical recognition Program meant to educate Canadians on the impacts of the head tax and the racism experienced by many different groups in Canada.

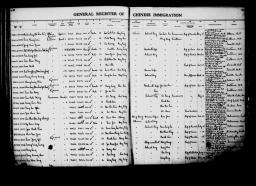

Dr. Henry Yu is now a professor of History at the University of British Columbia. He has played a key role in the Chinese Head Tax Digitization Project, which created a searchable database of Chinese Canadian immigrants who paid the head tax. The database allows individuals to search for family members, and it allows researchers access to important demographic information. For Dr. Yu, it also serves as a connection to his grandfather and to all those who have passed away, ensuring they and their stories are never forgotten:

"You could say that in this research, this database, I can find ways to hear from him and all those other men who are otherwise silent. And so that’s where, in a way, we were able to find a voice and let it say things that perhaps they couldn’t at the time."

The story of the Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act and the struggle for redress can be found in the Museum’s Canadian Journeys gallery. This blog was written in part using research conducted by Mallory Richard, who worked at the Museum as both a researcher and a project coordinator.

Author

Matthew McRae worked at the Museum as Researcher and as Digital Content Specialist.