The rights and freedoms we enjoy were fought for by those before us – those who refused to stay silent in the face of inequality and injustice. Their courageous actions inspire us to continue to work for the rights of all.

Rights of Passage (Level 6 - Expressions)

Experience 150 years of human rights history.

December 2017 to March 2019

This exhibition has passed.

Tags:

Photo: Dr. Geert van den Steenhoven

Exhibition details

About the Exhibition

Foundations and Dislocations (1867–1914)

Discover how Canadians talked about rights in the years following Confederation. Although few people used the term “human rights”, they were concerned with freedoms, including freedom of speech, religion, association and the press. However, these rights were narrowly defined and applied only to a privileged few.

Decorated with wooden accents, newspaper effects, and poster bills from the time period, this space includes an antique “magic lantern” that projects still images onto a wall.

Transformations and Interventions (1915–1960)

Two world wars and the Great Depression brought massive upheaval to Canada. Governments intervened in aspects of daily life, such as restricting movement of First Nations people through a pass system, interning Canadians with roots in countries at war with Canada, and restricting freedom of expression and freedom of the press. Many Canadians demanded a new role for government, seeking both political change and a new focus on meeting citizens’ basic needs.

Here you can leap back in time by turning the dials on a radio to listen to historic broadcasts.

Towards the Charter (1960–1982)

The 1960s and 1970s were turbulent years. As people increasingly challenged the status quo, Canadian society also became more diverse. Canadians held great debates on collective rights, national unity and identity. Popular protests and social movements helped steer the conversation towards the idea of a charter of rights and freedoms.

In this time period, you can interact with a vintage television set, and select from 13 news stories that help capture the spirit of the time.

Human Rights in a Contemporary Canada (1982‐present)

Since the enactment of the Charter in 1982, human rights have become part of Canadians’ everyday lives. This section looks at emerging human rights questions and debates including:

- The right to privacy in a digital age,

- The right to a clean and healthy environment in the context of massive pollution and climate change,

- The right to a gender identity of one’s choosing.

Explore Canada in the contemporary age with 'Facing the Future', a digital media interactive featuring holograms and wearable technology.

Defending Sovereignty (past and present)

Hundreds of Indigenous nations reside in what is now known as Canada. Since 1867, these nations have negotiated with a new foreign government – the Canadian state – that has systematically introduced policies to sever Indigenous peoples’ relationships with the land and environment and to destroy their identities and ways of life. This section, which includes elements of traditional medicine, distinctive art and beadwork, explores the concepts of sovereignty and reconciliation as they relate to Indigenous peoples.

In this space, you can watch oral history interviews and short films, or engage with a sound‐activated mosaic featuring artwork and perspectives of Indigenous youth.

The Stories

Rights of Passage: Canada at 150 is full of human rights stories. Thirty‐three stories in fact. We have selected five stories to share with you. How many did you know already? Visit Rights of Passage and discover a human rights story that you'll want to share!

The Bows and Arrows

Bows and Arrows union leader William Nahanee surrounded by a group of longshoremen, Vancouver, 1889. Local 526 fought for inclusion, respect, better wages and improved working conditions.

The Squamish First Nations’ ways of life were disrupted when a sawmill was built on Burrard Inlet, British Columbia, in 1863. Following that, many Indigenous men began to work on the waterfront. In 1906 they formed Local 526 of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The IWW sought to organize all workers, regardless of skill, race or gender.

Local 526 was known as the Bows and Arrows. Its leadership was mostly Indigenous. Members fought against racial prejudice on the waterfront and asserted the right of Indigenous people to unionize alongside non‐Indigenous workers.

One Woman’s Challenge

In 1941, Carrie Best learned that a group of Black teenagers had been forcibly removed from the “whites only” section of the Roseland Theatre in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia. She wrote a letter to the owner of the theatre and argued that all Canadians should have the same rights, regardless of race.

Carrie Best, founder and editor of The Clarion, the first Black‐owned newspaper in Nova Scotia, date unknown. The newspaper emphasized issues of racial justice and equality.

When the Roseland refused to change its policy of segregation, Best and her son Cal went to the theatre and defiantly sat in the “whites only” section. They were removed by a police officer and ended up in court. Carrie Best lost her trial; the judge did not acknowledge the racist policy of segregation.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms reflected Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s vision for a united nation based on equal rights for all Canadians. It resulted from a process of national consultation. People concerned with women’s rights, LGBTTQ rights, Indigenous rights, the rights of persons with disabilities, and others shared their views on the proposed Charter.

The Charter protects fundamental freedoms and democratic rights. It also prohibits discrimination on the basis of colour, religion, sex, age, and physical or mental disability. It affirms, but does not define, pre‐existing Indigenous and treaty rights. The Charter has been interpreted in different ways since its enactment, allowing the scope of its protections to evolve.

Queen Elizabeth II signing Canada’s constitutional proclamation, Ottawa, April 17, 1982. With this proclamation, Canada cut its last constitutional ties with the United Kingdom and established the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The enactment of the Charter was part of a broader agreement to transfer authority of the nation’s highest law – principally, the British North America Act – from Great Britain to Canada. This process was controversial. Some provinces were concerned that the federal government was acting unilaterally. The agreement was ultimately concluded without Quebec’s participation. Subsequent efforts to secure the support of all provinces failed. In 1990, Manitoba MLA and Red Sucker Lake First Nation Chief Elijah Harper refused to sign the Meech Lake Accord. He claimed the agreement did not adequately recognize the rights of Indigenous peoples. The subsequent Charlottetown Accord was defeated by popular referendum in 1992.

Manitoba MLA Elijah Harper holding an eagle feather, Winnipeg, June 19, 1990. Harper argued that Indigenous peoples had not been adequately consulted in constitutional negotiations.

Anti-Personnel Landmines and Human Security

In 1997, Canada became the first country to sign the Ottawa Treaty. It has now been ratified by 162 countries around the world. Those countries agreed to cease the production and use of landmines, to destroy existing stockpiles, to aid mine victims, and to participate in mine awareness education.

Mine awareness kit, 1992-1995

Canadian Armed Forces landmine experts used kits like this one from the United Nations Protection Force in the former Yugoslavia to teach locals to recognize and avoid landmines. Mine awareness kit: Canadian War Museum, 20030023–027.

Such efforts also illustrate a new focus on human security. This concept emphasizes the need to protect individuals from a broad range of threats such as armed conflict, disease, terrorism or natural disasters. Human security became an important part of Canada’s foreign policy beginning in the 1990s.

Foreign Affairs Minister Lloyd Axworthy receiving a standing ovation in the House of Commons, Ottawa, March 1999. Axworthy played a key role in securing global support for the Ottawa Treaty.

Far From Home

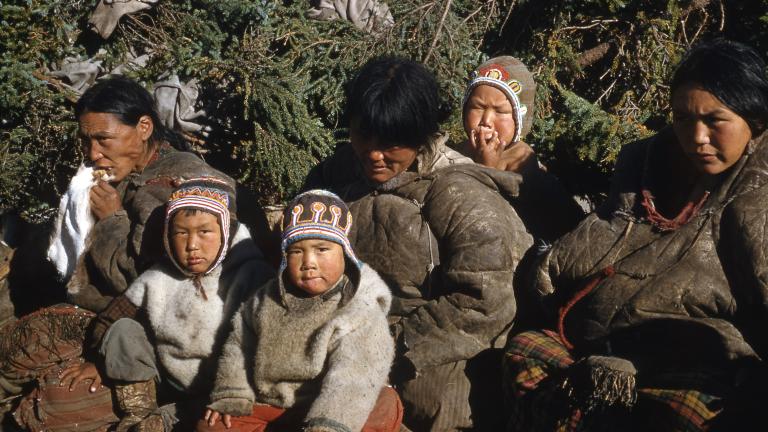

The Ahiarmiut of Ennadai Lake, also known as the Ihalmiut, were one of several communities forcibly relocated by the Canadian government between 1949–1958.

When the plane arrived to take the Ahiarmiut away from their homes, no interpreter was present. No notice was given. They were not permitted to bring tools or supplies. Starvation set in when caribou herds failed to appear in their new location.

Toy canoe, around 1956

Toys like this one were recovered on site when community members returned to Ennadai Lake in 1985, affirming the group’s connection to their lands. Toy Canoe: David Serkoak.

The rights of the Ahiarmiut were rooted in land and traditional knowledge. In 1985, community members went back home to Ennadai Lake. This return has led to renewed efforts to preserve their traditional knowledge and history.

Silas Illungiayok drum dancing while women sing in a circle at Ennadai Lake, 1985. For many Ahiarmiut, the trip in 1985 was the last journey home to Ennadai Lake.

Rights of Passage is featured in the Level 6 Expressions gallery, supported by the Richardson Foundation & Family. The exhibition runs from December 2017 to October 2018.