Did you know that in the not‐too‐distant past, Jewish people living in Canada were discouraged from visiting certain vacation spots or from purchasing or renting vacation properties?

The stain of antisemitism in Canada

A 1940s beach resort rejects the “unwanted”

By Jeremy Maron

Published: September 16, 2019

Tags:

Photo: Winnipeg Public Library

Story text

Victoria Beach, on the shores of Lake Winnipeg, was established as an exclusive resort community in 1910. It was envisioned as a tranquil retreat that would retain the natural character of its surroundings rather than becoming a popular leisure destination. In contrast to other resort areas on Lake Winnipeg that were founded by railway companies to create demand for passenger rail traffic, such as Winnipeg Beach and Grand Beach, Victoria Beach did not allow establishments like amusement parks or dance halls to be built. Cars were not (and are still not) allowed within the resort during the summer months. All of these restrictions ensured that the beach community would retain its exclusive nature as a popular retreat for Winnipeg’s wealthy elite.

The exclusive nature of Victoria Beach extended beyond a focus on class or status to include ethnicity and culture. Simply put, Jewish people were not welcome. These discriminatory attitudes were not kept hidden.

Exclusivity and exclusion

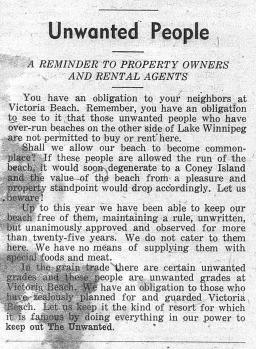

On August 14, 1943, during the Second World War, the Victoria Beach Herald published a front‐page editorial under the headline “Unwanted People.” This piece appealed to the exclusive nature of the community and advocated for the exclusion of certain groups considered undesirable.

The editorial began by stating to cottage owners, “You have an obligation to your neighbors at Victoria Beach. Remember, you have the obligation to see to it that those unwanted people…are not permitted to buy or rent here.”

The editorial did not explicitly say who the “unwanted people” were but in 1940s Canada, the intent would have been clear. Author Allan Levine, in his book Seeking the Fabled City, writes about how antisemitism was part of Canada’s cultural fabric.

“During the period from the early 1880s to the early 1960s, anti‐Semitism was ingrained in the fabric of Canadian society, imposed and practised openly, usually without hesitation, qualifications or shame. Shopping at a Jewish‐owned store or using the services of a Jewish tailor was tolerable for most gentile Canadians. But it was not acceptable to have Jewish work colleagues, Jewish neighbours or, worst of all, Jewish members at private sports and social clubs. That was just the way it was.”

For anyone in the community who might have had some doubts about who the unwanted might be, the article stated matter‐of‐factly that “we have no means of supplying them with special foods and meat” in reference to Jewish dietary customs.

The Winnipeg Free Press wasted little time publishing a condemnation of the antisemitic sentiments expressed in the nearby beach community newspaper. The editor of the Winnipeg Free Press, John W. Dafoe, had been outspoken about denouncing antisemitism since 1933. His editorial page response to the Herald was quick and decisive, calling the four‐paragraph piece a “sanctimonious and cowardly piece of Jew‐baiting of which Adolf Hitler and all his Nazis would loudly approve.” The Free Press rebuttal concluded by asking Manitobans how they felt about this racial discrimination, in no uncertain terms.

What have the people of Manitoba got to say about this manifestation in their midst of racial discrimination similar to that practised by the Nazis?

On August 21, 1943 – one week after the original editorial – the Victoria Beach Herald published a response to the Free Press rebuttal titled “The Barrier Must Be Maintained.” As the title suggests, this response doubled down on the sentiments of the original editorial by claiming “many residents would go even farther than the Herald statement has gone.” Moreover, it did not in any way deny or refute the charge of antisemitism made by the Free Press. The fact that the original piece did not reference Jews explicitly was not a careful evasion, but was indicative of just how unremarkable antisemitism was in Canada at the time, as Levine has pointed out. The original editorial didn’t have to spell out that Jews were the “unwanted people” because it would have gone without saying.

In those days, antisemitic sentiments were far from limited to Victoria Beach – they were common throughout Canadian society and politics. Four years before the Victoria Beach Herald article, Canada was one of the nations that refused to admit Jewish refugees trying to flee Nazi Europe on the MS Saint Louis. Canada’s racist and antisemitic immigration restrictions made it almost impossible for Jewish people to immigrate to Canada before, and during, the Second World War. One immigration official summarized Canada’s policy toward Jews at the time as “none is too many”1.

The history of antisemitism in Canada continues to spark discussion and dialogue in the 21st century, including at Victoria Beach. In 2012, St. Michael Church in Victoria Beach hosted a screening of the film The Paper Nazis, by Winnipeg‐based filmmaker Andrew Wall. The film explores the history of antisemitism in Manitoba and includes information about the exclusionary practices at Victoria Beach. Moved by the film and its exposure of this aspect of the community’s history, members of the congregation reached out to the Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada in Winnipeg to arrange a visit to the centre. After this visit, St. Michael Church gave a donation to the Jewish community as a gesture of reconciliation.

However, antisemitism remains a hateful force in this country. According to Statistics Canada’s latest police‐reported hate crime data, hate crimes against the Jewish population grew by 63 percent in 2017, from 221 to 360 incidents. In total, 18 percent of all police‐reported hate crimes were anti‐Jewish.

One of the most important responses to hateful expressions of antisemitism, racism and other forms of discrimination is to not let them go unanswered. Recognizing and calling out hate – like the Winnipeg Free Press editorial did – is a crucial step towards creating a human rights culture where discrimination against certain people simply because of who they are (or are perceived to be) is unacceptable.

To learn more about the history of antisemitism in Canada, visit the theatre in the Museum's Examining the Holocaust gallery on Level 4.

Ask yourself:

Are there people around us who are being treated like “the unwanted” now?

What can I do in my life to counter attitudes of exclusion?

How can I help to create communities where all people are respected and valued?

Reference

1 Irving Abella and Harold Troper, None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933–1948, Preface

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Jeremy Maron. “The stain of antisemitism in Canada.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published September 16, 2019. https://humanrights.ca/story/stain-antisemitism-canada

Continue the conversation

This story inspired thoughtful and personal discussion when we shared it on social media. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to join the conversation.

Josie Moriarty

facebook November 14, 2019 by Josie MoriartyJane Marie Werner Amiotte

facebook November 18, 2019 by Jane Marie Werner AmiotteSteve Lumpy Donaldson

facebook November 18, 2019 by Steve Lumpy DonaldsonContinue the conversation

Judith Cohen

facebook November 12, 2019 by Judith CohenNicola Timmerman

facebook November 12, 2019 by Nicola Timmerman