Most Canadians know the Romani people as “Gypsies,” mythical wanderers of the earth, travelling free spirits who shun both work and education. But for millions of Roma around the globe, discrimination, exclusion and persecution of their communities and culture has been anything but a myth. This is also true in Canada, where Roma struggle for recognition, inclusion and human rights. This is our story of activism against injustice, racism and discrimination.

We are Roma

We are not a Halloween costume nor “bogus” refugees

By

Gina Csanyi-Robah with Shayna Plaut, Ph. D.

Published: April 7, 2025

Tags:

Story text

Anti‐Roma discrimination and racially motivated violence have plagued our communities in Europe for centuries, leading thousands of European Roma to seek asylum as refugees in Canada. In 1956, during the Hungarian Revolution,[1] my family was one of them.

My maternal grandparents arrived by ship at Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. These grandparents were members of the Roma minority known as Cigany, which means “Gypsy’ in Hungarian.[2] They were survivors of the Holocaust — also known as Porajmos (“the devouring”) — when at least 500,000 Roma and Sinti[3] people were murdered by the Nazis and Nazi collaborators.[4]

Genocidal policies against the Roma of Europe date back centuries. In 1758, Queen Theresa of Hungary decided the way the deal with the “Gypsy problem” was forced assimilation into ethnic Hungarian (Magyar) culture.[5] Roma were barred from wearing traditional dress, speaking their own language and owning horses or wagons. In addition, Romani children were forcibly removed from their families and placed in ethnic Hungarian homes. The goal was to create “new Magyars” — dark skinned on the outside but with all their Romani identity and culture erased. These human rights violations resulted in profound intergenerational trauma.

That intergenerational trauma continued in Canada. My maternal grandparents lost custody of their six children when authorities moved to “save” the children from my grandparents’ home, a home which did not conform to the Anglo‐Canadian norm at the time. There is no doubt that negative stereotypes about “Gypsies” played a big part in this decision. As a result of being taken from their family at a young age, my mother and her siblings lost a huge part of their identity and were disconnected from the rich traditions of their Romani relatives.

Who are the Roma people?

The Roma are an ethnic group of millions of people worldwide who share ancestry, language and culture. We are the largest ethnic minority in Europe, where, according to the United Nations, at least 10–12 million Roma live. Our community is incredibly diverse, with varying skin tones and traditions, often influenced by the religions, languages and customs of the countries where we have lived for centuries. But although there is diversity in our cultures, the discrimination we face in Europe is fairly universal — and growing.[7]

In English‐speaking countries, Roma are often referred to as Gypsies. The term originated from the mistaken belief that we came from Egypt when we first arrived in Europe. In reality, we trace our origins to Northern India, having migrated through Iran, Afghanistan and Turkey, and then into Greece. By the 13th century, Roma were living throughout Europe.

Population estimates are tricky as many Roma in multicultural Canada choose to hide their ethnicity. That said, a recent research study I co‐led and co‐authored with Harvard University shows that, in Canada, our community now numbers over 100,000. The highest concentration resides in Toronto and Hamilton, Ontario.[8] We are from all over Europe, but most are from Czech, Slovak and Hungarian backgrounds and many, like myself, are second or third generation.

My journey of discovery

My father also arrived in Canada around the same time as my maternal grandparents. However, they were members of the white Hungarian (Magyar) majority. Growing up, even if I didn’t fully understand, I was keenly aware of the deep divisions between Hungarian Roma and Hungarian non‐Roma. I was told by my father to “hide my Gypsy identity because it was an embarrassment, and people would treat me bad.” The “people who would treat me badly” were his Hungarian friends who owned the restaurants in our Toronto neighbourhood.

I grew up experiencing that discrimination and internalizing a lot of shame. It was challenging to counter negative Gypsy stereotypes because it was nearly impossible for me to see my ethnicity represented in a positive way. I remember my aunt playing the famous song by Sonny and Cher, “Gypsies, Tramps, and Thieves.” This was my first realization that we are perceived as criminals. But there was more: every Halloween, kids wore Gypsy costumes to school. This confused me. Firstly, we don’t dress like that and secondly, if people don’t like us, then why are they pretending to be this fantasy version of us for a day?

When I was a teenager, my grandmother told me that her eldest sister had been taken to a concentration camp during the Holocaust. There, she endured horrific medical experimentation on her reproductive organs. I was deeply disturbed and also felt betrayed. I knew about the Holocaust but was never taught in school about the Roma persecution and genocide during this time. It was hard to learn that people hated us so much.

A couple of years later, when I was in grade 12, I went with a friend to watch a new Stephen King horror film. I left feeling embarrassed and mortified. The main character in Thinner lost weight rapidly due to a “Gypsy curse” placed on him from a witch‐like, old and scary woman. This popular film by someone famous left me feeling more embarrassed that I was a “Gypsy.” I had a feeling of hopelessness — we would always be a myth, not a people.

It wasn’t until the internet became available in the late 1990s that I began my journey of (re)discovery and was able to learn more about Romani history, culture and experiences for the first time. This is when I was also able to connect my mother back to the culture and history that had been forcibly taken from her.

Roma in Canada

In the 1990s, thousands of Romani refugees fleeing discrimination and racially motivated violence in Europe sought asylum in Canada — only to confront racism in this country, too. For example, in 1997, a small group of neo‐Nazis gathered outside a Scarborough, Ontario hotel where refugees and refugee applicants were housed. They carried signs with anti‐Roma messages like “Honk if you hate Gypsies” and shouted slogans like “Gypsies out!” At the same time, the Canadian government, and even a member of the Toronto City Council, was seeking ways to discourage Roma refugee claimants from exercising their right seek safety in Canada.

In response to this overt racism, pioneers of the Romani civil rights movement in Canada formed two non‐profit organizations. In 1996, Julia Lovell founded the Western Canada Romani Alliance, the first Romani organization in Canada. In 1998, Dr. Ronald Lee and Amdi Asonoski co‐founded the Toronto Roma Community and Advocacy Centre (RCAC).[9] In addition to teaching and sharing Romani culture and being a space for community, both organizations sought to support Roma refugees and to ensure they had the right to seek protection, guaranteed under international law.

In 1999, the RCAC staged its first demonstration to protest a decision by the Immigration and Refugee Board in Canada to use the findings of prior “lead cases” as a measure to assess all claims by Romani refugees from Hungary, rather than evaluating each case on its own merit. Lead cases had never been used before or have never been used since. The results were chilling. In 1998, over 70% of Hungarian Roma’s claims were accepted. By 2000, only 30% were accepted. At the time, immigration lawyer Rocco Galati said this institutional bias was aimed at “the most marginalized, non‐represented and alienated racial group.”[10]

Despite a long-standing historical presence in Canada, knowledge of the existence of Romani Canadians, their history, culture and contributions, as well as the contextual and cultural diversity and nuances that comprise the collective Romani identity, remains widely unknown in Canadian society.

My activism

In 2001, I saw a documentary from the National Film Board of Canada that changed my life. It was Opre Roma: Gypsies in Canada,[11] created by Julia Lovell. This is when Dr. Ronald Lee inspired me to become a Romani rights activist. Once I finished my undergrad degree at the University of Toronto, I spent a period of time in Europe, gaining knowledge about human rights laws and Romani rights activism. When I returned to Canada, I joined the board of the Toronto Roma Community Centre in 2007, then became its Executive Director in 2011.[12] In 2014, after moving from Toronto to Vancouver, it was an honour to co‐found (with my mentors, Julia and Lache) the Canadian Romani Alliance, an umbrella Romani‐led organization to provide advocacy and public education, and to build community capacity throughout Canada by bringing together different Romani organizations and leaders in the country.

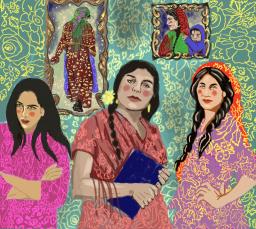

At the core of all our community activism lies anti‐racism work, which focuses on raising awareness about the truth of who we are and sharing our lived experiences. Sometimes this requires tackling overt racism, such as trying to take Sun News TV commentator Ezra Levant to court for racist remarks he made about Roma people in 2012. The Canadian Broadcast Standards Council found his hate‐filled rant had violated ethical standards.[13] Other times, it is disrupting the ideas people have about “Gypsies.” Our activism, often through the forms of education and art, is about making people aware that Roma are a people with history, culture and language — not a myth or a Halloween costume.

Correcting the past and looking towards the future

A significant amount of our Canadian Romani activism and advocacy has been for recognition and inclusion in Holocaust education, narratives and commemorations. As the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, this is particularly important to me. Until recently, the horror and intergenerational trauma that our community carries have been mostly invisible.[14] Dr. Ronald Lee, had been a strong activist for this recognition, and Dafina Savic, founder of Romanipe, and many others continue this journey. The fight for a seat at the table finally succeeded in 2014, when I was invited to join the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance as a delegate for Canada.

In 2019, after years of public education and political advocacy by Canadian Romani activists, especially Dafina Savic, and our allies such as the Montreal Holocaust Museum, Canada became the sixth country to officially recognize the Romani genocide during the Holocaust.[15]

A new battle: “bogus refugees”

In addition to ensuring that our historical persecution was accurately reflected, we have also fought ongoing discrimination and injustice against Roma people. For decades, much of our activism has been to enable Romani refugee applicants to receive a fair hearing and treatment in Canada.

Beginning in 2008, thousands of Romani families from Central Europe, primarily from the Czech Republic and Hungary, sought asylum in Canada, fleeing a wave of violent attacks by white supremacist and neo‐Nazi groups (some of which became part of the Hungarian government). These extremists terrorized Romani communities with impunity, while local law enforcement refused to hold aggressors accountable. In Hungary, a series of racially motivated murders left six Roma dead and many injured.[16]

In many cases, European Union governments failed to protect victims, although the persecution was recognized under international, European and domestic law. This lack of protection provided grounds for claiming refugee status. However, in Canada, these refugees faced a new threat. Despite extensive documentation by groups such as Amnesty International[17] of ongoing human rights violations against the Roma, Canada’s Minister of Immigration at the time called asylum seekers from European countries “bogus refugees.”[18] This government stance played into the age‐old racist stereotype that “Gypsies are swindlers.” His view had a devastating impact on the community. In 2008, 80% of Roma refugee claims were accepted, but following the “bogus refugee” label, the rate dropped to zero and stayed there for months before increasing again, though not beyond 20%.[19]

New legislation Bill C‑31, was introduced in 2012, which hampered the ability of Roma refugee claimants to have a successful asylum outcome. Most significantly, Bill C‑31 created the Designated Countries of Origin (DCO) scheme, which labelled most European countries as “safe.”[20] Refugee claimants from those countries had much less time to make their case and had restricted access to appeals. For Roma refugees, this ignored the reality of escalating hate crimes and systemic discrimination in Central and Eastern Europe. With the support of allies, and solidarity from members of the Jewish community, refugee‐serving community and socially conscious nurses and doctors, we began a relentless campaign to expose the danger of this policy.

In May 2012, I testified in front of parliamentary committees. I tried my best to convince these elected officials that Bill C‑31 was discriminatory toward Roma refugees and would have terrible consequences. Sadly, the law still passed. The DCO list remained in force until 2019 and continues to have effects to this day.[21]

The difficulty Roma refugees faced in Canada was exacerbated by the negligent misconduct of three Ontario‐based lawyers. Applications were prepared poorly, evidence was lost, and in some cases a lawyer didn’t show up for refugee tribunal hearings. As a result, almost all 985 Hungarian Roma refugee claimants who were clients of these lawyers lost their cases and were deported from Canada. The lawyers eventually faced disciplinary hearings, and one has been disbarred.[22]

The Redress for Roma Refugees Coalition sought justice for the way that Roma asylum seekers were unfairly treated by the government and some lawyers. We were a group consisting of lawyers, activists, academics, faith and community leaders.[23] My heart is filled with gratitude for the incredible care demonstrated in the volunteer efforts of this coalition.

The work that we did together reflects the values I was raised as a Canadian to believe in — the recognition that every person has the right to live a life of safety and dignity, free of discrimination and persecution.

Ask yourself

Can you imagine being part of an ethnicity and culture that most people think is make‐believe?

What is the difference between forced migration and nomadism?

How do stereotypes contribute to discrimination?

Authors

Gina Csanyi‐Robah (she/her) has been a Canadian Gypsy/Romani human rights activist since 2004. A former Executive Director of the Roma Community Centre in Toronto (2010–2013), she is currently the Executive Director of the Canadian Romani Alliance (2014–2025), which she co‐founded in Vancouver. In addition to her activism, Gina is a high school teacher and the proud mother of two beautiful children, Yasin and Eva. Together, they live, learn, play and work on the unceded and stolen ancestral lands of the Coast Salish peoples — the sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil‐Waututh) and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) nations.

Shayna Plaut, Ph. D. (she/her) is the Director of Research and Exhibition Development at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Shayna’s work sits at the intersection of academia, journalism and advocacy with a particular interest in people who do not fit in well with the traditional understanding of the nation state. Shayna has served as a consultant for the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Amnesty International and a variety of migrant and human rights organizations. Her 2023 book, The Messy Ethics of Human Rights Work, published by UBC Press, is a collaborative effort with four editors and 13 contributors providing an honest reflection on the uncertain and ever‐present grey areas of engaging in human rights work.

References

- In 1956, a popular uprising in Hungary was violently quashed by Soviet troops and hundreds of thousands of people fled the country to escape the repressive regime. Back to citation 1

- Although “Cigany” is commonly used, including in the official census and by Roma in Hungary, it is often perceived, and used, as a racial slur. Back to citation 2

- The Sinti are a group of Romani people found primarily in Germany and Austria. Back to citation 3

- The number of Roma who were killed is hotly contested and ranges from 0.5 to 1.5 million people. See, for example, Ian Hancock, 2004. “Romanies and the Holocaust: A Reevaluation and an Overview,” in Dan Stone (ed.), The Historiography of the Holocaust. Palgrave‐Macmillan, pp. 383–396. Back to citation 4

- This practice of creating “New Magyars’ continued throughout the century and spawned similar practices in Spain, Prussia and, in the 20th century, Switzerland. (Bancroft, 2005; Feischmidt, Szombati and Szuhay 2013; Varju and Plaut 2017) Back to citation 5

- There is an ongoing desire by the Elders and educators in our community to narrate our own story through publications, art and film to a larger, Romani and non‐Romani, audience. Among many significant public education initiatives was the creation of the first Canadian Romani newsletter, Romano Lil, edited by Hedina Sicerčič, a Bosnian Romani writer, teacher and activist. Another example is here: https://callthewitness.net/Testimonies/CanadaWithoutShadows Back to citation 6

- See: https://www.unicef.org/eca/what-we-do/ending-child-poverty/roma-children Back to citation 7

- https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.harvard.edu/dist/c/679/files/2024/09/FXB_CRA-Canada-Report-Final_Confronting-Major-and-Everyday-Discrimination-Romani-Experiences-GTHA.pdf Back to citation 8

- The Toronto Roma Community and Advocacy Centre was established with the support of Hedina Sijercic and Lynn Hutchinson Lee. Back to citation 9

- See Roma get no refuge — NOW Toronto. The use of “lead cases” ended in 2006. Back to citation 10

- “Opre Roma” translates into “Roma Rising” in the Romani language. Back to citation 11

- The Toronto Roma Community Centre is led by Michael Butch, a 4th generation Kalderash Rom, who has the amazing skill of bringing European and Canadian Roma together regardless of their countries of origin https://www.pressreader.com/canada/canada-s-history/20180601/282033327846022?srsltid=AfmBOopccoeH5UCmV6Ai0eGXdGk44a2zttS75P2wzRqFbn__AypD_Jaa Back to citation 12

- Roma Community Centre media release on CBSC ruling – Ezra Levant – Romanipe Back to citation 13

- Members of the Jewish community, especially Bernie Farber, former head of the Canadian Jewish Congress was particularly instrumental in bringing this hate speech to justice. In 2013, I co‐wrote an opinion piece in the National Post newspaper with Bernie Farber https://nationalpost.com/opinion/gina-csanyi-robah-bernie-m-farber-remembering-all-the-holocausts-victims Back to citation 14

- See: https://holocaustremembrance.com/what-we-do/focus-areas/teaching-learning-genocide-roma and https://www.canadianromanialliance.com/posts‑2/2020/8/30/canadian-government-officially-recognizes-romani-genocide Back to citation 15

- See https://www.errc.org/news/ten-years-after-the-roma-killings-in-hungary-theres-nothing-so-called-about-antigypsyism and https://www.errc.org/news/hungary-neo-nazi-murderer-finally-admits-his-guilt-13-years-after-the-roma-killings-and-confirms-two-members-of-the-death-squad-remain-free Back to citation 16

- See Hungary: Violent attacks against Roma in Hungary: Time to investigate racial motivation — Amnesty International Back to citation 17

- Refugee reforms include fingerprints, no appeals for some | CBC News Back to citation 18

- See “No Refuge: Hungarian Romani Refugee Claimants in Canada as well as Levine-Rasky’s “Exclusion of Roma in Canadian Refugee Policy” Back to citation 19

- Kenney names 27 countries as 'safe' in refugee claim dealings | CBC News. This policy had devastating effects on queer refugees as well as those fleeing gender‐based violence. Back to citation 20

- https://kitchener.citynews.ca/2023/04/05/hangover-from-discriminatory-policies-may-still-be-felt-by-roma-refugees-advocates/ Back to citation 21

- Deported Roma have little chance of return despite disciplinary rulings against their lawyers | CBC News Back to citation 22

- https://www.thestar.com/news/immigration/federal-government-urged-to-help-roma-refugee-clients-of-disciplined-lawyers/article_be23ce9d-88e0-5dac-bd64-2264f5c8292c.html Back to citation 23

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Gina Csanyi-Robah with Shayna Plaut, Ph. D.. “We are Roma.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published April 7, 2025. https://humanrights.ca/story/we-are-roma