From the 1880s to the 1990s, over 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children were torn from their families and sent to Indian residential schools, often located far from their homes. Many students suffered neglect and abuse. Thousands of children died.

Canada’s Indian residential schools: Childhood denied

Education and conversion as tools of colonial genocide

Published: September 20, 2018

Tags:

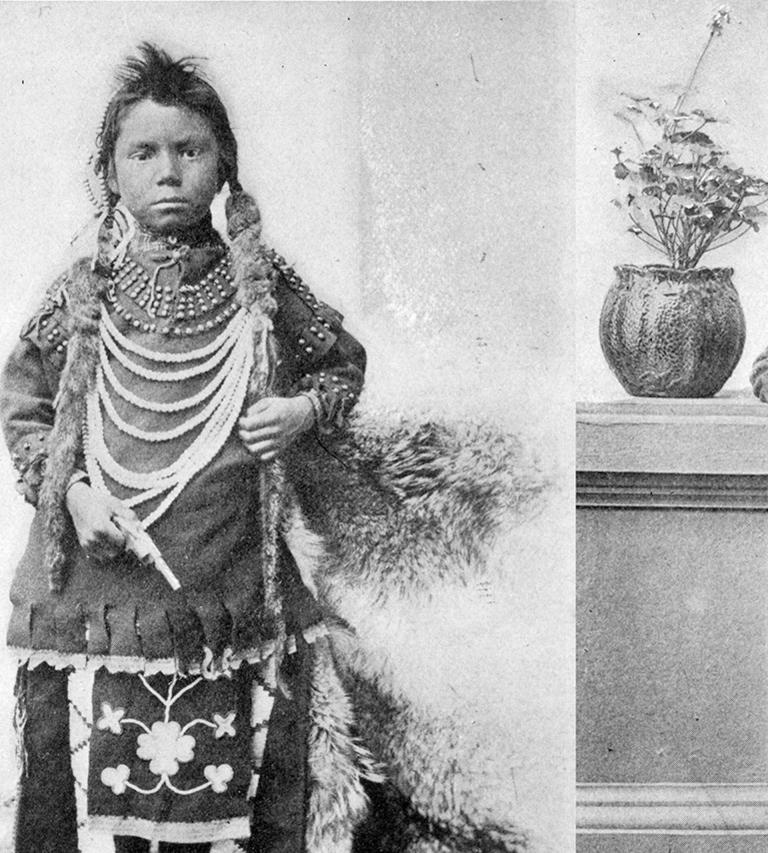

Photo : Yukon Archives, Anglican Church, Diocese of Yukon fonds, 86/61 #678

Story text

More than 100 Indian residential schools were established across Canada, in almost every province and territory. The Government of Canada used the schools, run by Catholic and Protestant churches, to remove children from the influence of their families and communities, language, culture and beliefs.

The deliberate, forcible removal of children from their families with the intent to destroy Indigenous culture and identity constitutes a genocide.

The system of federally supported schools was created to destroy Indigenous families, communities and ways of life, and to assimilate Indigenous children into European culture. As a result, for more than 100 years in Canada, First Nations, Métis and Inuit children were deprived of the love and attention of their families.

Assimilation and loss of identity

Many residential schools did not allow contact between children and their families. Others allowed occasional visits. As soon as Indigenous children were placed in Indian residential schools, they were forced to adopt the customs, language and culture of European society. School officials removed any personal or family items that children brought to the school. Children could not wear their own clothes. They were forbidden to speak their own Indigenous languages. Children were not allowed to keep their hair long, even though long braided hair carries cultural significance for many Indigenous people. The students were completely removed from their familiar way of life.

I want to get rid of the Indian problem... Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic.

The legacy of residential schools

The film Childhood Denied: Indian Residential Schools and Their Legacy includes survivors speaking about Indian residential schools, the 60s scoop and the child welfare system. In the 1960s, Canada's child welfare system continued to intervene in the lives of Indigenous families, by removing Indigenous children and placing them in non‐Indigenous homes. Indigenous children are still far more likely to be placed in foster or institutional care than other Canadian children.

Video: Childhood Denied: Indian Residential Schools and Their Legacy

The reason I wanted to tell my story was because our young people need to know…it needs to be told over and over and over again, so that they understand why we are the way we are. It’s going to take a lot of generations to be whole and healthy again.

Video: Mary Courchene

Mary Courchene, a survivor of the residential school system, explains how the trauma of the schools has affected generations of her people. (Video footage courtesy of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada)

Survivors speak out

Years of work by survivors speaking about their experiences brought increased recognition of what happened at Indian residential schools. The hard work and courage of survivors, communities and Indigenous organizations led to the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement in 2006. This settlement, between the Government of Canada and school survivors, included provisions for compensation and for the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. The Commission’s mandate included documenting and preserving the experience of survivors.

The Government of Canada apology

On Wednesday, June 11, 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper made a Statement of Apology to former students of Indian Residential Schools, on behalf of the Government of Canada. Hundreds of former students, church representatives and Indigenous leaders watched the apology from the House of Commons galleries. An excerpt from that apology is found below:

To the approximately 80,000 living former students, and all family members and communities, the Government of Canada now recognizes that it was wrong to forcibly remove children from their homes and we apologize for having done this. We now recognize that it was wrong to separate children from rich and vibrant cultures and traditions that it created a void in many lives and communities, and we apologize for having done this. We now recognize that, in separating children from their families, we undermined the ability of many to adequately parent their own children and sowed the seeds for generations to follow, and we apologize for having done this. We now recognize that, far too often, these institutions gave rise to abuse or neglect and were inadequately controlled, and we apologize for failing to protect you. Not only did you suffer these abuses as children, but as you became parents, you were powerless to protect your own children from suffering the same experience, and for this we are sorry.

The burden of this experience has been on your shoulders for far too long. The burden is properly ours as a Government, and as a country. There is no place in Canada for the attitudes that inspired the Indian Residential Schools system to ever prevail again. You have been working on recovering from this experience for a long time and in a very real sense, we are now joining you on this journey. The Government of Canada sincerely apologizes and asks the forgiveness of the Aboriginal peoples of this country for failing them so profoundly.

Nous le regrettons

We are sorry

Nimitataynan

Niminchinowesamin

Mamiattugut

— The Right Honourable Stephen Harper, Prime Minister of Canada

Honouring the truth

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission spent six years travelling across the country to uncover the truth of the residential school system. At national events, community hearings, forums and dialogues, the Commission heard from Indigenous people who had been taken from their families and spent much of their childhood in residential schools.

In 2015, the Commission released its final report. The report concluded that Canada committed cultural genocide, attempting to destroy structures and practices that identified Indigenous people as a group. In order to prevent cultural values and traditions from being passed down from one generation to the next, the schools forbade spiritual practices, banned the use of Indigenous languages and disrupted families by moving children to schools located far away from their home communities.

Recognizing genocide

The evidence the Truth and Reconciliation Commission gathered, including testimonies from Indian residential school survivors, sparked discussion in Canada about how the Indigenous experience of Indian residential schools is consistent with genocide.

The United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide defines genocide as "any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

a) killing members of the group;

b) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

d) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

e) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group."

The Indigenous experience in Canada meets the definition of genocide. The forcible transfer of children from their homes to Indian residential schools, cut off from family and community, with the intent to destroy families, communities and ways of life is genocide.

Survivors of residential schools carry trauma. But the trauma is also intergenerational. When caregivers of children are hurt by a genocidal system, the trauma is passed on to that child.

Moving forward with reconciliation

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission documented the truth of Indian residential schools, but it also focused on reconciling for the future. To the Commission, reconciliation is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Indigenous and non‐Indigenous peoples in Canada.

The Commission identifies four things that must occur for reconciliation to happen:

- awareness of the past,

- acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted,

- atonement for the causes,

- action to change behaviour.

The Commission made 94 calls to action in order to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of reconciliation in Canada. Some of the calls to action require the participation of governments, educational institutions and museums, but reconciliation can also start with smaller actions.

Over and above the calls to action, the Commission notes in its final report that "museums are well positioned to contribute to education for reconciliation." The Museum is fully committed to taking on this responsibility. Today, we recognize the genocide committed against Indigenous peoples in Canada in our student education programs, our public programs, online and in our exhibitions. We are committed to telling the difficult truths about the Indian residential school experience, and its ongoing effects, in order to advance the process of reconciliation.

Ry Moran, Director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation located in Winnipeg, Manitoba, says that in order to move forward towards reconciliation, there must be better understanding of the rights of Indigenous people.

Video: Ry Moran

Excerpt from interview with Ry Moran. Video: CMHR, Jessica Sigurdson

Reconciliation is always about relationships. It’s about bringing balance to the relations between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. At an individual level, people often ask, 'What can I do?' My answer to that is always, 'Look at how you believe and how you behave and how you think and change that.'

Ask yourself:

Do I recognize the wrongs committed at Indian residential schools?

Have I read the 94 calls to action?

What actions can I take to contribute to reconciliation?

Dive deeper

Canada’s residential schools

In this guide, you will find links to resources related to the residential school system and the stories of children who were taken from their families and sent to residential schools.

Why reconciliation? Why now?

By Karine Duhamel

Since the publication of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s final report in 2015, more and more Canadians seem focused on the idea of reconciliation.

Reconciliation: A movement of hope or a movement of guilt?

By Karine Duhamel

In Why reconciliation? Why now? I talked about the idea of reconciliation as an invitation to a new and shared future and as a pathway towards a good life, both for Indigenous people and for other Canadians.

The nuts and bolts of reconciliation

By Karine Duhamel

As a child, I often visited museums. I was lucky to be able to travel with my family, and to visit interpretive spaces across the country.

Approaching the human rights stories of Indigenous peoples

By Karine Duhamel

This article focuses on the creation and development of exhibition content exploring the human rights stories of Indigenous people in this country. To tell these stories, the Museum engaged with communities and individuals in a process of truth‐telling.

Truth and reconciliation: What’s next?

By Karine Duhamel

This article series has focused on the way we present Indigenous content within the Museum and how we are approaching reconciliation.

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : “Canada’s Indian residential schools: Childhood denied.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published September 20, 2018. https://humanrights.ca/story/canadas-indian-residential-schools-childhood-denied