Vladimir Kara‐Murza is one of Russia’s most outspoken advocates for democracy and human rights. A journalist, filmmaker and political activist, he has long been on the front lines of opposition to Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Fighting for a vision of a free and democratic Russia

An interview with Vladimir Kara-Murza

Published: October 22, 2018

Tags:

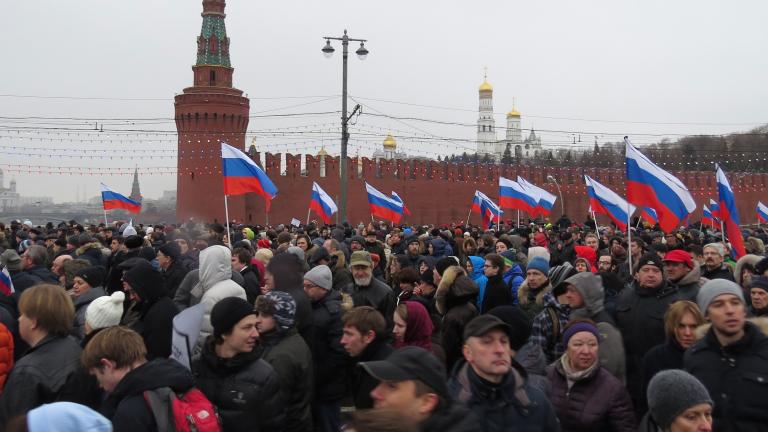

Photo : Wikimedia Commons

Story text

In 2015, Kara‐Murza was poisoned and nearly died – just three months after his close friend, opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, was gunned down on a bridge near the Kremlin. In 2017, Kara‐Murza was poisoned again, and once again survived. He left Russia and travelled extensively, raising awareness of corruption and human rights violations in Russia.

He lobbied governments to pass laws preventing corrupt Russian officials from channelling their wealth into offshore financial institutions. This campaign led to the passage of the Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act in Canada and the 2012 Magnitsky Act in the United States.

In early 2022, Kara‐Murza returned to Russia. He was promptly arrested and charged under draconian new laws that criminalize any criticism of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In remarks from October, 2022, when he was awarded the Václav Havel Prize for human rights advocacy, Kara‐Murza says: "With the start of this brutal invasion of Ukraine, Putin also launched another war — a war on truth in our own country…. Yet despite the arrests and the threats and the tidal wave of repression, thousands of Russians have voiced their opposition to the war on Ukraine."

Kara‐Murza spoke at the Museum in October 2018. In addition, he kindly answered some questions about his motivations, strategies, and goals. At the time, he led the group Open Russia, which advocated for democracy, due process and freedom of the press. Open Russia was declared “undesirable” in Russia in 2017. It was disbanded in early 2021 to prevent its members from being prosecuted under strict new laws restricting political dissent.

Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR): Can you tell us a little bit about your background and what shaped your interest growing up in Moscow?

Vladimir Kara‐Murza: When I was 10 years old, something happened in front of my eyes which shaped who I am and what I do in life. It was the Russian Democratic Revolution of August 1991 – the three days that changed course of history and put an end to the decades‐long Soviet communist regime, one of the most oppressive regimes in the history of mankind.

They had the police, the army, the KGB, and the tanks which they sent to occupy central Moscow. All the Russian people who wanted to stand up for their rights and freedoms were not armed with anything except their dignity and their determination. My father was among those people. The lesson was that, at the end of the day, a people is always stronger and mightier than a dictatorship – because when those tanks came into Moscow, they were confronted with hundreds of thousands of unarmed, peaceful people who flooded the streets and literally stood in the way of those tanks. And the tanks stopped and turned away.

When I became an adult, I dedicated my life to human rights advocacy through the campaign for democracy in Russia. Unfortunately, it’s a campaign that continues to be relevant because we’ve had an unfortunate return to many of the practices of our bad totalitarian past. After Vladimir Putin came to power, he very quickly reinstated many of the old symbols but also many of the old practices of our old authoritarian past. And today, unfortunately, Russia is a country that isn’t free.

Our elections are a sham orchestrated by the government where all the major media are controlled and guided by the state, where people can be beaten up and arrested for going out to peacefully protest and peacefully express their views. Many of those who dare to actively oppose the current regime are harassed, are in exile, are in prison or are no longer with us. In February of 2015, the most prominent, the strongest leader of the democratic opposition in Russia — former deputy prime minister Boris Nemtsov, who was a very close friend of mine as well as a colleague for many, many years — was assassinated, gunned down on the bridge in front of the Kremlin in what was the most high profile and the most brazen political assassination in modern Russia.

CMHR: You yourself have been twice poisoned. What motivates you to continue to speak out?

VKM: I know that the truth is on our side and that the future is on our side. I think our country deserves so much better than having a corrupt authoritarian autocracy that is stealing from and abusing the most basic rights and freedoms of the people of Russia. Russia is a wonderful country with a great and very rich culture, with so many talented, intelligent people. We want Russia to be a country that respects the rights of its own citizens, respects the rule of law at home and behaves as a responsible member of the international community.

We have a whole generation in Russia who have grown up not knowing any other political reality from the current regime, who have only seen Putin’s face on the television screens their entire lives.

The vision of a free and democratic Russia is one that we have to continue to fight for. Over the last year and a half, all across the country, tens of thousands of people have been going out to the streets to protest against this regime and its corruption and its authoritarianism and its arrogance and its impunity. We have a whole generation in Russia who have grown up not knowing any other political reality from the current regime, who have only seen Putin’s face on the television screens their entire lives. It is that generation that is increasingly saying: “Enough!” They are, very literally, the future of Russia. And it is for their sake and for their future that we have to continue to do what we do.

CMHR: One of your messages is that sanctions are the best way for the international community to support the fight for freedom and democracy in Russia. Canada passed the Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act last October, what many people refer to as Canada’s Magnitsky Act. Can you talk about your role in that legislation?

VKM: These laws lay out a very basic but ground‐breaking principle in international affairs: that the people who are complicit in human rights abuses, corruption and stealing from their own citizens will no longer be able to travel to the West, own assets in the West or use the financial and banking systems of the West. Because it’s in the West where these people open their bank accounts, buy real estate, educate their children, own luxury cars and yachts and so on. That is what the Magnitsky Act puts a stop to. It introduces the notion of personal, individual accountability instead of slapping general sanctions on a whole country, which are unjust and very often counter‐productive.

I am proud of the small role I played in this process over the past eight years working with parliamentarians in many western countries including Canada, where I came to testify three times before different parliamentary committees. We are deeply grateful to members of the Canadian parliament and who passed this law unanimously in October of 2017, not a single vote against. And, by the way, Boris Nemtsov also travelled to Canada in 2012 to speak on Parliament Hill in Ottawa in support of this legislation. So far, six countries have passed similar laws. Most recently, I went to testify at the Parliament of Denmark in support of the same legislation and hopefully in the next few weeks will be going to Paris to testify the French National Assembly.

It is very important to put an end to this impunity and show to these people who are continuing to abuse the rights of their own citizens and continue to steal the money of their own citizens that this behavior will no longer be tolerated and that the people who violate the norms of democracy in their own countries will no longer be able to enjoy the fruits and the privileges of democracy in the West. Human rights are universal and so accountability for abusing human rights should also be universal.

CMHR: I believe you said there’s a danger of giving Russian president Vladimir Putin too much legitimacy on the international stage. Is that the case?

VKM: Vladimir Putin has now been in power for almost two decades, and for the first several years of his rule, we saw too many countries give him the red carpet treatment, which he did not deserve and that legitimized him in a way that he shouldn’t have been. Very quickly after he became president of Russia, Putin moved to restore not only the symbols of the Soviet past like the Soviet national anthem, but also many of the methods of the Soviet past like media censorship, manipulated elections, politically motivated prosecutions and so on. But, astonishingly, while Putin was doing this, he still continued to receive red carpet treatment from the West – I suppose as a misguided and naïve attempt to strike some sort of accommodation to make deals with Vladimir Putin on the international stage and turn a blind eye to what he was doing domestically. Yet anyone who knows Russian history knows that domestic repression and external aggression in our country always go hand in hand. There’s no reason to expect a government that violates the rights of its own people and breaks its own laws and its own constitution to respect international law or the interests of other countries.

There’s no reason to expect a government that violates the rights of its own people and breaks its own laws and its own constitution to respect international law or the interests of other countries.

So it is heartening to see finally in the last few years, many western countries realize how mistaken this approach was. Sometimes, though, we’re seeing the other extreme now, where people in the West ascribe the actions and the crimes of the Putin regime to Russia as a whole. They don’t differentiate between a small clique that is sitting in the Kremlin and a country of 140 million people. People should stop saying “Russia” when they really mean “Putin”.

CMHR: How do you think the rise of new communication technologies and the widespread use of social media support or work against what you’ve called domestic repression?

VKM: Of course, the new technologies and social media the Internet are being used very shrewdly by totalitarian regimes around the world and Vladimir Putin’s regime is no exception. We hear a lot about the so‐called trolls that are very effectively being used by the Kremlin to flood the online space in Russia and elsewhere. But I think the overall effect is undoubtedly positive. The only access to objective, uncensored information that Russian citizens have today is the access provided by online resources. And this is a space where we can operate and where millions of Russian people can find the truth about what is happening in our country and the world. The truth beyond the official state media, which presents a distorted propaganda image.

The only access to objective, uncensored information that Russian citizens have today is the access provided by online resources.

I’ll give you one specific example. Last year, Alexei Navalny, who’s a prominent anti‐corruption campaigner in Russia, produced an investigative documentary into the secret financial empire of the current Russian prime minister, showing his hidden assets, his yachts, his villas, his mansions and his vineyards in Italy and many, many other things. Not a single word was said about that investigation on the national television networks, which are all controlled by the government. Yet 25 million people in Russia watched that investigative documentary on YouTube, on Facebook, on Twitter, and tens of thousands of people went to the streets all across Russia to protest against this egregious corruption.

CMHR: You mentioned young people taking to the streets. Is that where you see hope for Russia?

_60.jpg?itok=mPcUfXVC)

VKM: Absolutely. The vast majority of those people who have been going out to the streets all across Russia over the past year are in their late teens and their early twenties. I think it’s a very hopeful and optimistic sign. They’re very literally the future of Russia. And it is remarkable that this is a generation that has spent their entire lives under Vladimir Putin – so you would think they would be completely brainwashed by Kremlin propaganda, and yet it is this generation that is increasingly going to the streets to say, “Enough! Enough of corruption, enough of human rights abuses, enough of the lies and propaganda!” And it is, in fact the young people who are the primary target audience for our work in Open Russia. We want to help empower them to become active and informed citizens.

CMHR: In closing, I’m wondering what advice you could give to ordinary Canadians about how they might have an influence?

VKM: I would not be exaggerating if I said that there wouldn’t be any Magnitsky legislation in the US, in Canada or in any other country without active public pressure from citizens who appeal to their own governments to stop acting as enablers for foreign dictatorships and for foreign corrupt officials by welcoming them and their dirty money into your countries and into your banking and financial systems. So I would be very grateful to Canadian citizens if they would continue to put pressure on their government to stand up for democracy and rule of law and human rights, not to just pay lip service to these principles and values but to actually practice what they preach and to behave in conformity with these values.

.jpg?itok=7sacxpOa)

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : “Fighting for a vision of a free and democratic Russia.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published October 22, 2018. https://humanrights.ca/story/fighting-vision-free-and-democratic-russia