On the afternoon of September 13, 1870, Elzéar Goulet entered Winnipeg’s Red Saloon. Little did he know that it would be his last visit. Singled out by other patrons for his role in the Red River Resistance, he was chased by a mob out into the street. Elzéar fought for his life – and lost.

The murder of Elzéar Goulet and the struggle for Métis rights

Resistance, violence and the founding of Manitoba

By Karine Duhamel

Published: September 10, 2020

Tags:

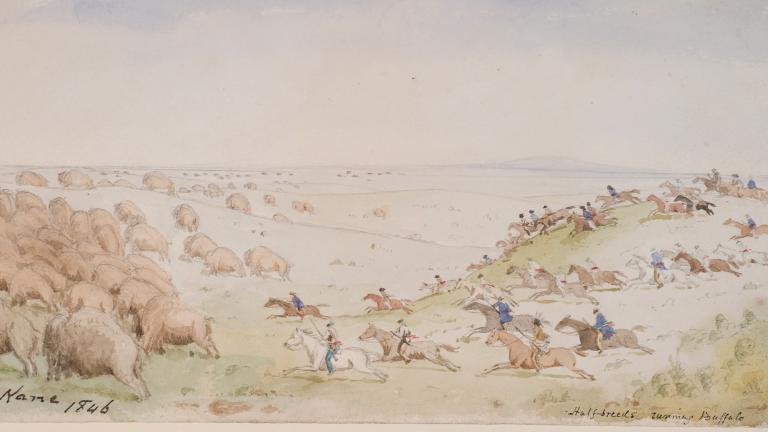

Stark Museum of Art1

Story text

He was only 34 when he was killed, but Elzéar Goulet had already led a storied life. A child raised in the traditions of his family, Elzéar’s Métis identity was closely associated with the trapping and trading work of his parents and grandparents. His family also had deep connections with the growing movement to assert the territorial and self‐governing rights of the Métis.

His life and his murder were tightly tied to the movement to define and defend Métis rights as Manitoba was being made part of the recently formed Dominion of Canada. His role in the history of the Métis and of the province of Manitoba deserves wider recognition, as a participant in the Métis resistance and a compatriot of Louis Riel.

The fur trade

For generations, Elzéar’s family had been deeply connected to the fur trade. His maternal grandfather was a Scotsman, John Siveright, who began working for the North West Company in 1799, at first in northwest Ontario, and later at Portage La Prairie, Manitoba.

In 1816, Siveright was charged as an accessory in the murder of Governor Robert Semple and 22 Scottish settlers. As representatives of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), this group of settlers engaged in a firefight with Métis traders from the North West Company at the Battle of Seven Oaks, just west of Winnipeg. Political and even violent conflict was a constant reality during this time of colonial expansion, which involved an increasing spread of colonial control over traditional Indigenous territories.

The charges against Siveright were later dropped and he continued to work for the North West Company for the next several years in Sault Ste. Marie. Siveright’s wife – Elzéar’s grandmother – was a Métis woman named Louise Roussin from Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

Elzéar’s paternal grandfather, Jacques Goulet, worked for the North West Company in Athabasca as a voyageur from 1804 until the merger of the North West Company and the HBC in 1821. Jacques continued to work for the HBC’s Saskatchewan District until he retired.

Alexis Goulet, Elzéar’s father, was also a Company man. Born in St. Boniface in 1811, Elzéar worked for the HBC as an oarsman on a York boat and then became a free trader in the Red River Settlement.

Seeking recognition of Métis ways of being

Elzéar’s father was passionate about the cause of Métis rights. He was one of 22 Métis buffalo hunters, free traders and freight carriers who met on August 29, 1845, to sign a letter to the Red River colonial authorities demanding the Métis right to hunt and to trade at a fair price. Alexis and his fellow Métis petitioners rejected the HBC’s control over prices and trade that dominated life and work at Red River.

As Natives of this country and as half breeds, [we] have the rights to hunt furs in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s territories where we think proper, and again sell those furs to the highest bidder.

The letter highlights the rising tensions in the region and its demands reflect a Métis worldview founded on important ideas about the freedom to live, trade and self‐govern according to Métis traditions. Within this worldview, the central concepts of Kaa‐tipeyimishoyaahk and Wahkotowin were central.

Kaa‐tipeyimishoyaahk roughly translates to the idea of self‐ownership, or “we are those who own ourselves.” For the Métis, this meant a state of autonomy and independent political action, free from external coercion, and an ability to self‐govern and regulate.

Wahkohtowin was an important guidepost to this system, referring to the responsibility of being related to other beings as family, triggering collective obligations to one’s relatives and to a larger network of kin.

These traditions were developed and shared within families and through the principles and practices of the buffalo hunt, which Elzéar likely participated in as a child with his father Alexis. They implied a commitment to the principles of Métis governance, which often formed in response to specific threats or events and disbanded after the fact, and which embodied an independent spirit and way of life.

Métis resistance

Clearly, Elzéar came of age during a time of colonization and conflict. And as an adult, he was directly involved when these growing tensions erupted in 1869.

In 1867, the country of Canada had come into being, governing a relatively small portion of what we know as Canada today. Only two years later, the fledgling Canadian government bought Rupert's Land from the HBC. This vast territory stretched from the southern Rocky Mountains north around Hudson Bay to Baffin Island, northern Quebec and Labrador. It also included the Canadian prairies and the settlement at Red River.

Canada promptly began to assert control over these lands. An English‐speaking governor, William McDougall, was appointed to impose direct colonial rule over the Canadian prairies.

Thus, in 1869, the independent Métis way of life seemed very much under threat. Changes were afoot in Red River territory. Its residents, who had not been consulted, were taken by surprise when McDougall sent out surveyors to plot the land, measuring and mapping according to the square township system being imposed by Canada. It was at this point that the Métis, led by Louis Riel, prevented McDougall from entering the territory.

Elzéar, now a young man, joined an organized group of Métis led by Riel in 1869 at a barricade at the bridge across the LaSalle River, blocking off the primary north‐south route between the colonial settlements of Pembina and Upper Fort Garry. The barricade was intended to stop Canadian government officials from claiming land occupied by the Métis.

Riel’s provisional government

As a captain in Riel’s provisional government, Elzéar played a key role in many of the important events of this tumultuous time.

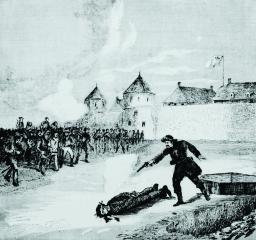

He served as a member of the court martial for Thomas Scott. Scott was a government surveyor and member of the Orange Order, a Protestant group that was opposed to Riel and Métis concerns. He was accused of treason against Riel’s provisional government and was executed by firing squad in March of 1870.

After the execution, Elzéar, along with another person, was given the responsibility of disposing of Scott’s body. Rumours circulated that they had dressed Scott as a Métis and dumped his body in the Red River. This supposed treatment further inflamed the anger and hatred from Scott’s fellow Orangemen and their government allies about the execution and fueled calls for Riel’s capture.

Manitoba becomes a province of Canada

The Manitoba Act, 1870 received royal assent on May 12, 1870, and constituted Manitoba as a province of Canada.

It is worth remembering that the Manitoba Act was based upon a list of rights the Métis prepared in defense of their land, language and traditions. This list of rights aimed to ensure the right to French‐language and English‐language education and services, equally; to uphold a tolerance for Catholicism, in the face of a new Protestant order; and to support the traditions of kinship and self‐ownership that had preserved Métis ways for so long.

Despite the achievement of this agreement, racial tensions flared because of Scott’s execution and uncertainty around the implementation of the Act. In light of these potential threats, a military expedition led by Garnet Joseph Wolseley was deployed to Upper Fort Garry in August 1870. The expedition was tasked with taking control of Red River until its new Lieutenant Governor, Adams George Archibald, arrived. Though Riel and many members of his provisional government fled, fearing for their lives, Elzéar chose to stay.

The mob attacks

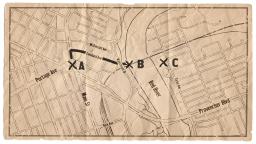

And so Elzéar found himself outnumbered and out of options on the afternoon of September 13, 1870. He had decided to go to the Red Saloon at the corner of Portage Avenue and Main Street. The saloon was known as a rowdy place and was located very close to where Colonel Wolseley’s troops were garrisoned at Upper Fort Garry. It was undoubtedly a bold move to walk in. But Elzéar did. He was soon recognized, and an angry mob chased him into the street.

Elzéar ran from his pursuers but didn’t succeed in outrunning his fate. At the end of Lombard Avenue, Elzéar dove into the Red River from the steamboat landing located there, trying to swim his way to safety in St. Boniface. Those in pursuit began to throw stones from the shore.

Elzéar was knocked unconscious while swimming and drowned in the Red River. His body was recovered the next day and he was eventually buried in St. Boniface.

Aftermath

In the aftermath of his death, Lieutenant Archibald called an inquest, appointing two magistrates from the HBC to hear from 20 witnesses. Despite warrants prepared for Elzéar’s pursuers, no arrests were ever made.

The frenzied mob in pursuit hurled missiles of all kinds at the hunted man and stoned him to death in the water.

Elzéar’s murder wasn’t the only case of vigilante violence against Métis during this time. As historian Fred Shore has written, “Assaults, ‘outrages,’ murder, arson and assorted acts of mayhem were practiced on the Métis anytime they came near Fort Garry, while the situation in the rest of the Settlement Belt was not much better.”2 These acts were reported in newspapers in Red River, St. Paul, Toronto and Montreal as the “Reign of terror” at Red River. The violence prompted many Métis families to leave the settlement and seek safety in the United States, as Riel had done, or in other provinces.

[It] just sent the message to Métis that [if] you show your face on the west side of the river… we’re going to beat you, we’re going to kill you, and if you think you’re going to get any help from the Canadian authorities now that we’re established here, forget it.

In 2007, then‐city councillor and Métis Dan Vandal petitioned to have a park named after Elzéar.

“It's not very well known, but it's one of those remarkable Winnipeg stories, and Winnipeg needs these stories, I think… to be brought to life,” said Vandal at the time.

Elzéar Goulet Park, at 718 Taché Avenue in St. Boniface, now stands as a permanent monument to the violence that occurred that fateful day.

How we remember and who we remember remains fundamental today to the stories we tell about ourselves and where we come from. Elzéar’s story, though unique, tells a larger tale than a simple murder by the mob – it’s a story about the very history and character of Manitoba, as it was made.

Ask yourself:

What past events still affect my family or community today? Do various communities remember these events differently?

How did I learn the history of the place where I live? Are there people whose stories tend to get left out of that history?

How much do I know about the traditions and culture of people from different backgrounds who live in my community?

References

- 1 Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas, 31.78.12 7, “Metis Chasing the Main Buffalo Herd” (1846) by Paul Kane (1810–1871), bequest of H.J. Lutcher Stark, 1965

- 2 Fred J. Shore, "The Métis: Losing the Land," Aboriginal Information Series (August 2006, Number 9), Office of University Accessibility. University of Manitoba.

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Karine Duhamel. “The murder of Elzéar Goulet and the struggle for Métis rights.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published September 10, 2020. https://humanrights.ca/story/murder-elzear-goulet-and-struggle-metis-rights