When Madeleine Kétéskwēw Dion Stout1 was seven years old, her appendix almost burst. Living in the Kehewin Cree Nation in 1953 in Alberta, there were no doctors or nurses, no clinic or hospital nearby, not even a telephone to call for help. But there was omâmâwa – her mother.

Nursing and Indigenous peoples’ health: reconciliation in practice

Nurses working for respect, fairness and social justice for First Nations, Inuit and Métis

By Maureen Fitzhenry

Published: March 2, 2021

Tags:

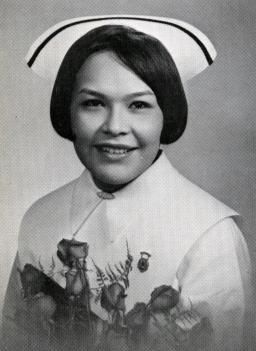

Photo: Madeleine Dion Stout

Story text

Sarah Youngchief Dion was a careful observer of the wellness of her family and community, learning from experience, nature and Elders. And she had seen her brother‐in‐law die of acute appendicitis.

“My parents hitched the horses to the wagon and we headed off to the town,” says Madeleine, now 74 years old. “The ride was only 10 miles, but by horse and wagon it took a long time. It was a very bumpy and painful ride.”

When they finally arrived at Elk Point Hospital, Madeleine saw what she thought was an angel – a freckle‐faced, bespectacled angel, dressed all in white, with a white‐winged cap adorned with a black‐velvet ribbon.

“I’d never seen anyone who looked like that nurse. And she was very, very kind to me. I have never forgotten her face or gentleness. From that point on, I wanted to be like her.”

That memory and omâmâwa’s influence led Madeleine to enter a career in nursing in 1965. A few years later, she became one of the first Indigenous women in Canada to graduate from a university‐level nursing program. Among many remarkable achievements as a trailblazer on issues related to First Nations health care, she became a founding member of the Canadian Indigenous Nurses’ Association (CINA).

Labour organization created to remove barriers

CINA was created in 1975 to help improve health outcomes for Indigenous peoples (a term that includes First Nations, Inuit and Métis) and to support Indigenous nurses (there are now about 9,000 in Canada). Indigenous communities in Canada have long faced obstacles to accessing health care in a system that has had little understanding of their history, cultures, languages and rights.

The organization was profiled in an exhibit at the Museum in 2020 called Rights on the Job, about the achievements of organized labour. Madeleine’s original white uniform and cap, along with her nursing graduation pin, were on display in the exhibit. Her mother’s black shawl and a piece of rat root commonly used as traditional medicine were included, unlabelled, in the display alongside Madeleine’s things to silently honour her mother and the healing tradition that inspired and influenced her.

Access to quality health care is not just a matter of where people live, says Dr. Annette Browne, a nursing professor at the University of British Columbia (UBC) who has collaborated with Madeleine on research projects for more than 25 years.

It’s also a matter of nahi miýw‐āyāwin, which in Cree describes fairness, wellness, a focus on values and recognition of inequities that result from offences against human dignity such as poverty, racism, sexism and violence.

“We need to push the thinking beyond physical or geographic access,” says Annette, whose research has generated a body of evidence aimed at improving health and health care, and at challenging social inequities for Indigenous and non‐Indigenous people.

“We need to more actively work against the ongoing negative assumptions about Indigenous peoples that are so commonplace in Canadian society – assumptions that affect the kind of care people receive, and their experiences when seeking care.”

Preconceptions and bias influence health care

Unfortunately, these barriers to fair and effective health care are not going away. In fact, Annette says there is growing research showing that inequities continue to deepen. For example, First Nations, Inuit and Métis people are less likely to be referred to specialists for diagnostic procedures, which impairs access to services such as cancer care or kidney dialysis. “If you have preconceptions about certain people being more deserving than others of referrals to specialists or for diagnostic tests, that is going to create inequities in access,” she says.

As a result, says Madeleine, many Indigenous people don’t feel welcomed by the health‐care system. “It can be really alienating to us.”

Madeleine is a survivor of Indian day school and residential school (which she attended for three years), where she experienced health‐care inequities first‐hand. Her first cousin died of tuberculosis in residential school.

“There are many kinds of poverties, including the poverty of affection, understanding, participation and marginalization that continue to exacerbate health inequities,” Madeleine says.

Reconciliation through respectful relationships

The path forward, these nurse‐researchers believe, is rooted in reconciliation, with a focus on building mutually respectful relationships between Indigenous and non‐Indigenous people. Their own long‐standing partnership is a prime example.

Annette is not Indigenous, but of Jewish heritage. Her grandmother survived the pogroms in Russia. Originally from Winnipeg, she graduated with a nursing degree from the University of Manitoba and immediately began working as a nurse in northern, remote Inuit and First Nations communities.

“People’s sense of family, community, laughter and wellbeing were central to community life,” she says. “I saw how these elements sustained and nurtured everyone.”

In 1995, Annette’s colleague, Dr. Jo‐Anne Fiske, suggested she contact Madeleine, who at the time was Director of the Centre for Aboriginal Education, Research and Culture at Carleton University. They have been working together on research projects ever since. In Yiddish, their meeting might be called bashert (באַשערט), meaning it was destined or meant to be.

When they met, Madeleine was already known as one of Canada’s Indigenous nurse leaders. She had spent years providing nursing services to First Nations people at their bedsides and in their communities before she moved into the policy arena. She has since been awarded honorary doctorates from three universities, the Centennial Award from the Canadian Nurses Association, and an Indspire Award. She was appointed to the Order of Canada in 2015.

Among their collaborations, Annette and Madeleine have explored the effects of inequities in health care, drawing from the Cree concept of nahi, or fairness. In particular, they have embraced Call to Action 22 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, which calls for the Canadian health care system to value Indigenous healing practices and use them in the treatment of First Nations, Inuit and Métis patients, in collaboration with Elders and healers.

One of their research projects showed how a drop of good intentions creates ripples of opportunities for First Nations, Inuit and Métis to shape health policies in the best interests of their communities. Together, and with other colleagues, they have also studied the impact of strategies such as Elder‐led circles to support the health of Indigenous women experiencing violence. “It’s necessary to understand how important cultural practices and ceremony are to Indigenous peoples,” says Madeleine, who is a fluent Cree speaker and incorporates Cree concepts and phrases into most of her health research papers.

Alycia J. Fridkin, Annette and Madeleine published this diagram in 2019 to show the interconnected concepts and actions required to support meaningful involvement of Indigenous peoples in health policy decision‐making. Decolonizing and transforming the power dynamics inherent in our health systems is necessary to create equity in health care. CMHR, Jeffrey Taniguchi. Adapted from Fridkin, A., Browne, A. J., & Dion Stout, M.2

And then, there’s omâmâwawak. Their mothers.

It’s a thread in their relationship that has brought them together more deeply.

“Madeleine and I recognize in one another the deep connections and influences of our mothers in our lives and how profoundly they have shaped our work,” says Annette.

Annette’s mother was the renowned choreographer, teacher and dancer Rachel Browne, who founded Canada’s longest‐running modern dance company, Winnipeg’s Contemporary Dancers. “My mother, grandmother and father instilled in me the values of social justice, and the work we can do to be helpful to others,” she says.

One of Rachel Browne’s well‐known pieces, called “Mouvement,” draws on imagery related to Mexican artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Wounded Deer.” When Annette saw a picture of Madeleine adorned with a deer‐antler crown during an awards ceremony, she was immediately reminded of that dance.

For Madeleine, learning about the dance brought back childhood memories of the deer hunt. Her father would bring home the bounty to skin and butcher, giving the children broken leg bones they could probe for raw marrow with sticks whittled by her grandfather. It was a joyful and healthy time.

Annette and Madeleine now call one another Nicâkos, meaning my fellow‐star, my soulmate, my kindred spirit, my sister‐in‐law, in Cree. When they part company, they wish one another Zei gezunt, a Yiddish word for “Be well.”

Through recognizing aspects of themselves in each other, the two women have forged a bond that reaches across their profoundly different backgrounds to a place of mutual trust, friendship and support.

And this is the place where reconciliation begins.

Ask yourself:

How can I make personal connections with people from different backgrounds and traditions in my community?

What does reconciliation mean to me? What does reconciliation look like in my family, community, nation and society?

Who are my role models for good physical, mental and spiritual health? What have they taught me about health, fairness and social justice?

Footnote and reference

- 1 Kétéskwēw is a Cree word that means “ancient woman” or “child with an ancient spirit.”

- 2 “The RIPPLES of Meaningful Involvement: A Framework for Meaningfully Involving Indigenous Peoples in Health Policy Decision‐Making.” The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 10.3 (2019). DOI

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Maureen Fitzhenry. “Nursing and Indigenous peoples’ health: reconciliation in practice.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published March 2, 2021. https://humanrights.ca/story/nursing-and-indigenous-peoples-health-reconciliation-practice