On March 21, 1960, police officers in a Black township in South Africa opened fire on a group of people peacefully protesting oppressive laws. Sixty‐nine protestors were killed. The anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre is remembered around the world on March 21, the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

The Sharpeville Massacre

A violent turning point in the history of South African apartheid

By Matthew McRae

Published: March 19, 2019 Updated: August 8, 2023

Tags:

Photo: Peter Magubane

Story text

Apartheid and the pass system

The Sharpeville Massacre occurred in South Africa during the era of “apartheid,” a racist legal system that denied rights and freedoms to anyone who was not considered white.

White people were a minority in South Africa, making up only 15 percent of the population. But they stood at the top of politics and society, wielding power and wealth. Black South Africans made up 80 percent of the population but were marginalized, repressed and relegated to the very bottom. White colonial authorities had used racist laws and violence to repress the Black population long before the formal creation of apartheid. But the imposition of apartheid formalized and intensified white supremacist discrimination and inequality.

Apartheid means "apartness" in the Afrikaans language. It was formally endorsed, legalized and promoted by the National Party (NP). The NP was narrowly elected in South Africa in 1948 by an almost exclusively white electorate.

Apartheid laws placed all South Africans into one of four racial categories: "white/European," "native/black," "coloured" (people of "mixed race"), or "Indian/Asian." These laws restricted almost every aspect of Black South Africans’ lives.

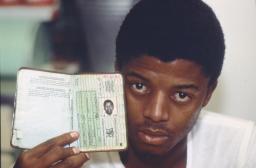

Some of the most restrictive laws were "pass laws." These laws forced Black South Africans to carry special identification that police and other authorities could check at any time. The government used passes to restrict where Black South Africans could work, live and travel.

Similar laws had existed before apartheid, but under apartheid, they became much worse. Pass laws were used to confine the Black population to specific Black‐only settlement areas. They were also used to control and exploit Black workers, who could be forced to live far away from their homes and families. Millions of Black South Africans were arrested, jailed, and brutalized under the authority of these repressive laws.

The origins of apartheid

Apartheid was firmly rooted in South Africa’s colonial history. As in Canada and other colonized regions, European powers violently displaced Indigenous communities and took control of their lands. By the time the NP formally imposed apartheid, the white minority controlled almost all – 92 percent – of the land.

The NP emerged from centuries of conflict among Dutch and British colonizers and Indigenous communities. The Party was formed mainly of Afrikaners – descendants of Dutch colonizers – who believed they had a God‐given mission to establish white rule in Africa. After the NP was elected in 1948, it quickly passed laws to further entrench longstanding practices of segregation, racial oppression and white supremacy.

Resistance and Sharpeville

For years, many South Africans peacefully protested against apartheid laws, including the pass system. In March 1960, a group called the Pan African Congress (PAC) decided to organize a protest in the Black township of Sharpeville. The plan was for protestors to march to the local police station without their passes and ask to be arrested, in an act of civil disobedience.

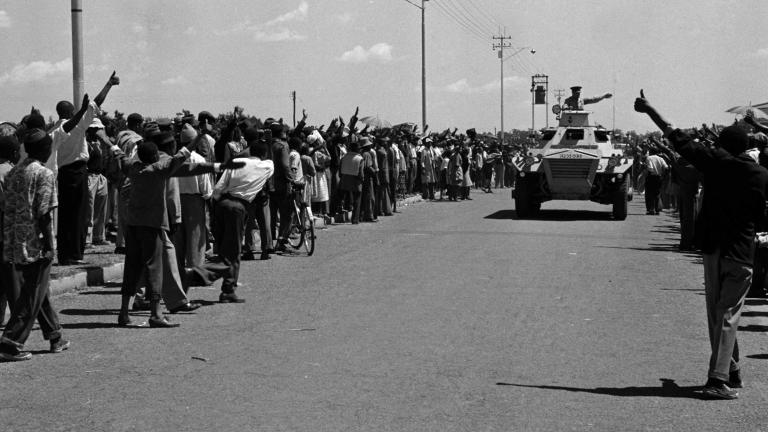

On March 21, thousands of South Africans marched to the Sharpeville police station. They gathered in peaceful defiance, refusing to carry their pass books. They chanted freedom songs and shouted, "Down with passes!" Simon Mkutau, who participated in the protest, would later recall: "The atmosphere was cheerful; people were happy, singing and dancing."1 However, as time went by, more and more police began to appear, along with increasing numbers of armoured vehicles. Military jets began to fly overhead.

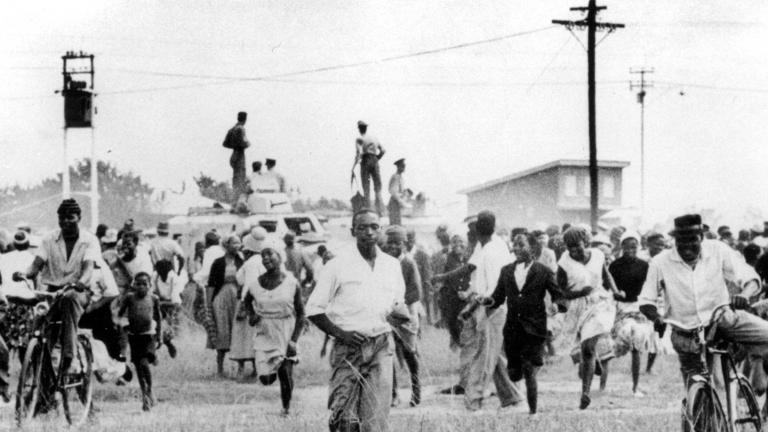

Then, without warning, the police opened fire on the unarmed crowd. Lydia Mahabuke was there when it happened. Mahabuke tried to run but felt something hit her in the back. "After having felt this, I tried to look back. People were falling, scattered. There was blood streaming down my leg. I tried to hobble. I struggled to get home."2

In total, 69 people were killed and more than 180 people were injured, mostly shot in the back as they fled the violence. A later report would state over 700 bullets had been fired, all by police.3

Afterwards, some witnesses claimed they saw police putting guns and knives in the hands of dead victims, to make it look like the protestors were armed and violent. Others said they saw police mocking people who they found alive. Some even claimed that the police killed injured people as they lay on the ground. In some cases, police followed the wounded to the hospital, arrested them and took them to prison. In other cases, the police waited until victims had healed somewhat, then arrested them.4

While we were standing there and singing we suddenly saw the police in a row pointing their guns at us. Whilst we were still singing, without any word, without any argument, we just heard the guns being fired.

The aftermath of the massacre

After the arrests, people in Sharpeville were afraid to talk about the tragedy. "In the days after the shootings, nothing happened," said Albert Mbongo, who participated in the protest and managed to escape without injury.5 "Nobody dared say anything," said Mbongo, "because if you did you were arrested. I couldn’t even attend the burial, because only women and children were allowed there."

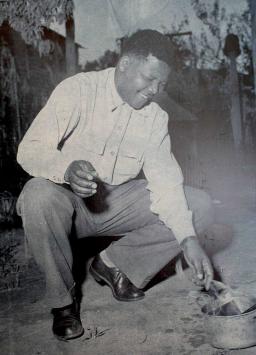

Away from Sharpeville, however, many people did express their outrage both inside and outside South Africa. To protest the massacre, Chief Albert Luthuli, the President‐General of the African National Congress (ANC) burned his own pass. Nelson Mandela and other ANC members also burned their passes in solidarity. Shortly afterwards, on March 30, approximately 30,000 protesters marched to Cape Town to protest the shootings.6

The international response to the massacre was swift and unanimous. Many countries around the world condemned the atrocity. On April 1, the United Nations (UN) Security Council passed a resolution condemning the killings and calling for the South African government to abandon its policy of apartheid. A month later, the UN General Assembly declared that apartheid was a violation of the UN Charter. This was the first time the UN had discussed apartheid.[7] Six years later, as a direct result of the Sharpeville Massacre, the UN declared March 21 to be the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

March 21 is the day on which we remember and sing praises to those who perished in the name of democracy and human dignity.

Sharpeville and the fight against apartheid

After Sharpeville, South Africa’s government had become increasingly isolated, but the government refused to abandon its policies of apartheid and racial discrimination. First, the government declared a state of emergency and detained around 2,000 people. Then, on April 8, 1960, both the ANC and PAC were banned – it became illegal to be a member of these organizations.

Many members of both organizations decided to go underground. Nelson Mandela was among those who chose to become outlaws. He would later say, "We believe in the words of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that ‘the will of the people shall be the basis of authority of the government,’ and for us to accept the banning was the equivalent of accepting the silencing of Africans for all time."8

Mandela and others no longer felt they could defeat apartheid peacefully. Both the PAC and the ANC formed armed wings and began a military struggle against the government. Many long years of struggle and suffering lay ahead – but Sharpeville was the beginning of the end for apartheid. Prakash Diar, a South African human rights lawyer, explains: "The whole world was outraged at what the police had done. On March 21, 1960, the isolation of South Africa started."

The eyes of the world would turn to Sharpeville again years later. During the 1980s, Diar would defend six people unjustly charged with murder by the apartheid government. The five men and one woman would become known as the Sharpeville Six – their case would attract international attention, once again putting Sharpeville on the world stage and exposing the inhumanity of the apartheid government.9

In December 1996, two years after the end of apartheid, South Africa enacted a new constitution whose Bill of Rights affirmed the values of dignity, equality and freedom for all South Africans. It was signed by President Nelson Mandela in the town of Sharpeville, very close to where the massacre had happened. In South Africa, March 21 is now known as Human Rights Day.

It took a long time, but the isolation and boycott of South Africa slowly started, because what they were practicing was inhumane and unjust.

Ask yourself

How are people resisting injustice in your community?

What kinds of human rights activism make a difference?

How can we ensure our governments respect human rights?

Dive deeper

The Story of Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela spent 27 years in prison for opposing South Africa’s apartheid system. He faced harsh conditions meant to break his resolve, but Mandela refused to give up his efforts to achieve equality for all people.

References

- 1 Lodge, Tom, Sharpeville: An Apartheid Massacre and its Consequences (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 4.

- 2 Ibid, 10.

- 3 Venter, Sahm, Exploring Our National Days: Human Rights Day 21 March(Auckland Park: Jacanda Media, 2007), 22.

- 4 Lodge, Tom, Sharpeville: An Apartheid Massacre and its Consequences, 13–14.

- 5 Ibid, 17.

- 6 The Road to Democracy in South Africa: Volume 1 [1960–1970] (Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2010), 239.

- 7 Dubow, Sam, Apartheid 1948–1994, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 83.

- 8 Asmal, Kader, David Chidester and Wilmot James, éd., Nelson Mandela in his Own Words: From Freedom to the Future, London, Abacus, 2013, p. 30.

- 9 You can read the story of the Sharpeville Six in Prakash Diar’s book, The Sharpeville Six (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Inc., 1990).

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Matthew McRae. “The Sharpeville Massacre.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published March 19, 2019. Updated: August 8, 2023. https://humanrights.ca/story/sharpeville-massacre