According to Indigenous Knowledge Keepers, the history of the Two Row Wampum begins in 1613, when Mohawk people noticed newcomers entering their territory and clearing land. A delegation of Haudenosaunee was dispatched to meet with Dutch representatives to negotiate a relationship with the new peoples now occupying Haudenosaunee land.

As Onondaga Faithkeeper Oren Lyons recounts, the Two Row Wampum agreement was created to agree on how the nations would relate to one another.

When the Dutch suggested that the Mohawk call them “father,” the Mohawk suggested an alternative – “brother” – to indicate a more equitable and autonomous relationship. The Haudenosaunee marked this agreement through beads on a wampum belt. The wampum belt has been referenced as an artifact and as an object but, as with any other document, it is read by those who understand its language.

The wampum stands for equity and respect, depicting two boats each navigating the river of life without steering the other. Each boat contains the life, laws and people of each culture. The agreement is to last “as long as the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, as long as the rivers run downhill, and as long as the grass grows green.” In other words, this agreement is to last as long as the people do.

The agreement was expanded and affirmed nearly 150 years later in 1764 at the Treaty of Niagara, where more than 2,000 chiefs renewed and extended the Covenant Chain of Friendship, a multi‐nation alliance between Indigenous nations and the British Crown. The proceedings included a reading of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which places a duty upon the Crown to engage in treaty‐making with Indigenous peoples.

Officials also read wampum belts, including the Two Row Wampum, to all those assembled, in order to affirm the spirit and intent of the relationship. Indigenous nations that were present believed the agreements affirmed their powers of self‐determination for as long as the people live on the land.

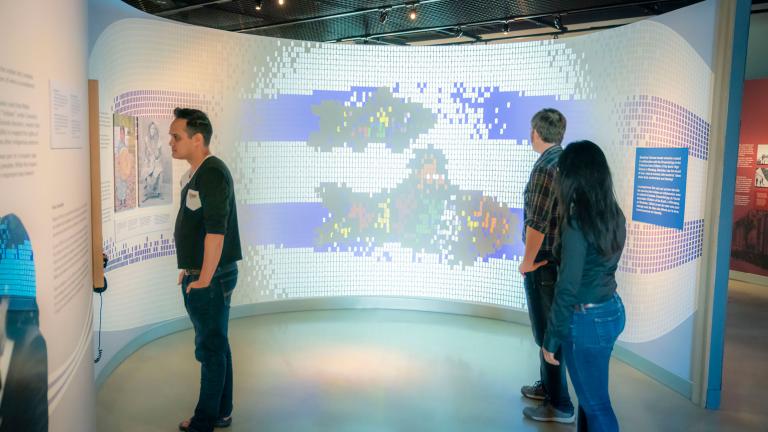

Four hundred years after its inception, the principles of the Two Row Wampum are foundational elements in the Museum exhibition Rights of Passage: Canada at 150. The exhibition contains a zone devoted to historical and contemporary Indigenous perspectives on rights, entitled “Defending Sovereignty.” This zone is about peace, friendship and respect, as illustrated by a graphic rendition of the Two Row Wampum that runs throughout the entire zone.

The graphic leads into a digital wampum bead projection that reacts to the sound, pitch and volume of visitors’ voices. Entitled “Speaking Volumes,” this interactive feature was developed in collaboration with the talented students from Omazinibii'gig Artist Collective at Children of the Earth high school in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Over the course of a half‐day workshop, students thought about what Indigenous rights meant to them. Their artistic expressions were then digitally recreated so that they could be projected onto the Two Row Wampum when visitors speak.

Some of these student artists visited the exhibition on its opening weekend. Speaking to media about the project, one student talked about being proud of his work and excited about its representation in the space. Another commented that the space itself felt like a welcoming one for Indigenous people.

The meanings of the Two Row Wampum – peace, friendship and respect – seem as relevant today as they were in 1613. In my life, I show peace by living with an open mind and being ready to hear new perspectives; I show friendship by supporting people in their endeavors and by lending a hand when I can; and I show respect by honouring all people, equally, as human beings. Institutions, like people, can also honour these principles, and in doing so, begin to engage in meaningful reconciliation.

Author

Karine Duhamel Dr. (she/her) is an Anishinaabe historian and a member of Opwaaganasiniing (Red Rock Indian Band) in northwestern Ontario. She holds a Bachelor of Arts and a Bachelor of Education, as well as a master’s degree and PhD in history. She served as Director of Research for the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (NIMMIWG) from 2018 to the end of its mandate in 2019. In 2021, she was awarded the Bruce and Lis Welch Community Dialogue Award through the Simon J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue at Simon Fraser University for her work with the Inquiry. In 2021, she chaired the data working group for the MMIWG2S+ National Action Plan. In 2022, she joined the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada as Director of Indigenous Strategy, working to implement the Tri-Agency strategic plan to better support Indigenous research and research training in Canada.

In addition to her role as a public servant, she is an official Speaker for the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba, an Indigenous fellow at Simon Fraser University, and a Research Affiliate of the Centre for Human Rights Research at the University of Manitoba.