In the beginning, Turtle Island was queer. Put another way, gender and sexuality were not understood in binary, “either/or” terms before the arrival of Europeans.

What Is Two-Spirit? Part One: Origins

Recognizing Indigenous gender and sexual diversity, resisting colonial norms

By Scott de Groot

Published: March 26, 2024

Tags:

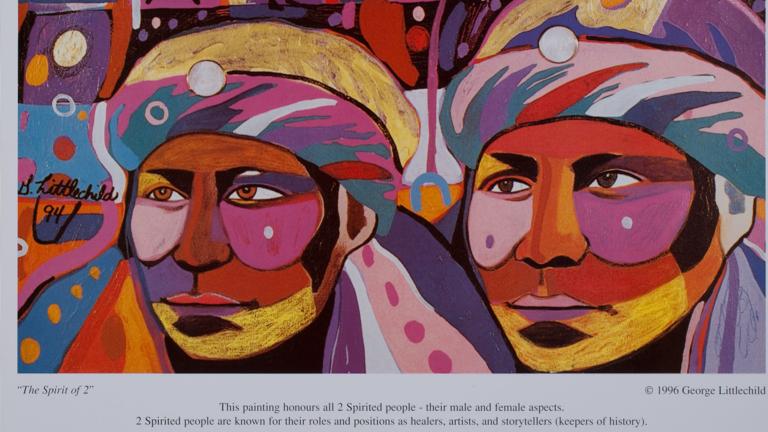

Credit: Oakland Museum of California, painting by George Littlechild.

Story text

Across Indigenous North America, some people lived their lives as neither men nor women. Some were seen as combining – even transcending – masculine and feminine characteristics. They performed important social roles, held knowledge, led ceremonies, reared children, married and lived in same‐sex relationships.[1]

Of course, Turtle Island was not simply a queer nirvana. Various customs and taboos governed gender and sexuality. Social norms varied greatly between First Nations. But a common thread throughout these nations was the lack of strict division of people into two opposing camps of men and women based on biology. No single system of morality forbade and condemned same‐sex and same‐gender relationships. These things only appeared later with Christianity and colonialism.

Indigenous languages have many words and expressions for people we would now call Two‐Spirit. Cree contains at least six. In Anishinaabemowin, there are at least four.

Selected Cree expressions[2]

| Cree | English |

|---|---|

| Napêw iskwêwisêhot | A man who dresses as a woman. |

| Iskwêw ka napêwayat | A woman who dresses as a man. |

| Ayahkwêw | A man who dresses, lives or is accepted as a woman. |

| Înahpîkasoht | A woman who dresses, lives or is accepted as a man. |

| Iskwêhkân | One who acts or lives as a woman. |

| Napêhkân | One who acts or lives as a man. |

Ma-Nee Chacaby

Born in 1950, Ma‐Nee Chacaby was raised in Ombabika – a remote Oji‐Cree community in Northwestern Ontario. She disliked wearing girls’ clothes and loved spending time in the woods. She fished and hunted, and helped Elders collect plant medicines.

Her community had been strongly impacted by residential schools. Forced conversions to Christianity had instilled strict, binary ideas about gender and sexuality in many people. Ma‐Nee was bullied for being too masculine. She was called “devil child” and mocked by neighbours. But her grandmother, who was over 90 years old, pushed back against this abuse.

She had been born before the creation of Canada in 1867. She recalled a time when people like Chacaby were respected and celebrated. She asserted that Ma‐Nee should be given space to develop her own preferences, talents and gifts.

Here, Ma‐Nee describes the profound impact her grandmother had on her upbringing.

Video: Ma-Nee

Ma-Nee’s path to become a celebrated Two‐Spirit Elder was difficult and winding. As an adult, she experienced homelessness, addiction and homophobic attacks. But her grandmother’s influence helped her in her difficult journey. She found strength in knowing that Two‐Spiritedness is a gift that is bound up with Indigenous worldviews and traditions.[3]

‘There’s two great spirits living inside of you. One is a female, one is a male,’ she said.

Albert McLeod

When Ma‐Nee Chacaby and her grandmother resisted attempts to impose a narrow version of femininity, they were resisting colonialism. Elder Albert McLeod, describes colonialism as not only claiming territory and extracting resources but also imposing strict, Christian gender roles. He notes that the imposition of European forms of gender and sexuality were central to the overall project of colonialization in Canada.

As Canada extended its borders and territorial claims after 1867, Indigenous sovereignty was attacked and eroded. Colonial power was not only exerted in areas such as politics and economics, but also in deeply personal domains of everyday life. New Canadian laws enforced Christian forms of marriage and co‐habitation. Polygamy and same‐sex relationships were criminalized.[4] The government attempted to destroy Indigenous cultures by removing children from their families and “re‐educating” them in Indian residential and day schools.

Staff at the residential schools divided children strictly according to binary male/female genders. Boys and girls had separate dorms and classrooms and were often forbidden from speaking to one another. They were dressed, styled and taught lessons deemed appropriate to their gender. Girls learned sewing and domestic chores. Boys were taught woodworking and other trades. Indigenous youth who displayed non‐binary forms of gender expression or queer desire were severely punished.[5]

Albert talks about the imposition of European social norms as connected to broader colonial processes of forced assimilation, land dispossession and genocide:

Video: Albert Colonialism

By the mid‐20th century, colonial laws and practices had repressed Indigenous worldviews and cultural practices across Canada. The Indian Act, the reserve system and the power of the church conspired to punish and suppress Indigenous gender and sexual diversity. Many people we would now call Two‐Spirit went underground. They even went into hiding within their own communities, which were now dotted with church spires and administered by Indian agents. However, in the late 1960s and 1970s, organized resistance to both colonialism and homophobia within Indigenous communities began to emerge.

In this period, the Red Power movement arose to demand sovereignty and self‐determination for Indigenous peoples throughout Turtle Island (what is now Canada and the United States). Simultaneously, the Gay Liberation movement challenged homophobia, asserted gay pride and encouraged queer people to come out of the closet. Queer Indigenous activists were influenced by these two movements, but also experienced marginalization within both of them. Gay liberationists tended to denounce colonialism abroad – such as in Vietnam – while ignoring settler colonialism at home.[6] They sometimes expressed racist attitudes and colonial standards of beauty. Red Power circles tended to be homophobic and emphasized macho gender roles, while ignoring Indigenous forms of sexual and gender diversity.

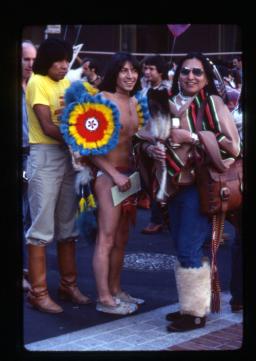

Drawing on some aspects of these movements while abandoning others, queer Indigenous activists opted to create independent organizations that would better address their needs. The first of these groups, Gay American Indians was founded in San Francisco in 1975. Others included American Indian Gays and Lesbians in Minneapolis, Gays and Lesbians of the First Nations in Toronto, WeWah and BarCheeAmpe in New York City, and Nichiwakan in Winnipeg.[7]

The Birth of Two-Spirit

Queer Indigenous activists on both sides of the Canada/United States border saw the need for greater communication, relationship‐building and coordination. They established an annual international gathering. In 1988, the first was hosted by American Indian Gays and Lesbians in Minneapolis. A second was held at a wilderness site in Wisconsin in 1989.

These events brought queer Indigenous people together to socialize, share their experiences and ideas, engage in cultural and spiritual practices, and learn from one another. A third gathering was held in Manitoba in the summer of 1990. It took place at a wilderness site outside Winnipeg, near Beausejour, Manitoba, along the banks of the Brokenhead River.

The summer of 1990 was a period of intense Indigenous activism and resistance in Canada. The Oka Crisis, also called the Kanesatake Resistance, began in July 1990. It became a 78‐day armed standoff between Mohawk (Kanyen'kehà:ka) protesters and the Canadian military and the Royal Canadian Mounted Policy (RCMP) in Quebec. That June, Manitoba Legislative Assembly member Elijah Harper voiced the concerns of Indigenous peoples across the country when he rejected the Meech Lake Accord. This was a proposed revision to Canada’s Constitution. Harper asserted that First Nations had not been appropriately consulted or recognized. He held up the Accord’s ratification in the Manitoba legislature, effectively killing it.

Against this backdrop, Myra Laramee had a consequential dream on the grounds of the Manitoba legislature. She is a Cree woman who was active in local queer community organizations. She was there to protest Manitoba’s colonial politics of child welfare and custody. In the tepee of an Indigenous mother on a hunger strike, Myra dreamt of seven spirits. Shifting between male and female forms, two of these spirits declared that Laramee was niizh manidoowag. This Anishinaabemowin term translates into English as “Two‐Spirited” or “Two‐Spirit.” Myra shared her dream at the third, transnational gathering of Indigenous queer activists held in 1990.[8]

Here, Albert explains the process of selecting a site for the gathering that gave birth to Two‐Spirit as an identity and the importance of the event.

Video: Albert McLeod

At this gathering, participants discussed and debated Two‐Spirit as a term. It seemed to link contemporary LGBTQ+ experiences with Indigenous traditions, histories and worldviews. And it arrived at the perfect time. Many community members were already searching for alternatives to offensive, colonial terms such as berdache, which had been used by missionaries and anthropologists. Ultimately, attendees at the 1990 gathering embraced Two‐Spirit as a new and positive expression of who they were. They did not seek to define Two‐Spirit in a narrow way.

Two‐Spirit was not intended to supplant other LGBTQ+ identities. It can easily coexist with terms such as gay or trans in an individual’s self‐understanding. Similarly, it was not meant to replace specific terms for non‐binary sexuality and gender in Indigenous languages. Rather, it acts as a contemporary umbrella term that fosters pan‐Indigenous interconnections.[9]

Simply put, Two‐Spirit was (and is) about self‐determination, rejecting colonial labels, building community and reconnecting with long‐suppressed aspects of Indigenous histories and cultures, including spirituality.

We had sharing circles, sweat lodges. We’re learning about the medicines, we’re learning the traditional songs. That was something that we were curious about that we couldn’t get from the broader gay community.

Charlotte Nolin

Born in Winnipeg in 1950, Charlotte Nolin was taken from her family as part of the Sixties Scoop. Assigned male at birth, she was shuffled between foster homes in southern Manitoba and was abused both at home and at day school. Charlotte ultimately escaped the foster system in her late teens. Turning to sex work and dealing drugs to survive, she moved back and forth between Winnipeg and Vancouver and spent stints in jail in both cities. Understanding that she was trans from a young age, Charlotte lived as a woman for brief periods when it was not too dangerous. She first heard the term Two‐Spirit at a sweat lodge ceremony in British Columbia in 1990. And something truly clicked in her self‐understanding.

Charlotte describes identifying with the term and its spiritual impact on her:

Video: Charlotte 2S

Charlotte was far from alone in experiencing this term as powerfully resonant. After 1990, subsequent gatherings were renamed International Two‐Spirit Gatherings. Throughout the 1990s, many Indigenous LGBTQ+ groups changed their names to include the term Two‐Spirit and entirely new groups were formed. By the 21st century, Two‐Spirit organizations existed from California to Ontario, from British Columbia to Texas.

The term Two‐Spirit filled an important need. Its articulation in 1990 offered people a meaningful connection with Indigenous traditions and identities and a distinct role in struggles for both decolonization and 2SLGBTQI+ liberation.

The second part of “What is Two‐Spirit?” will explore what Two‐Spirit means to Elders and knowledge keepers now, amid ongoing struggles for equity and inclusion in community and ceremony.

For me that’s walking in balance. You have both that male and female spirit.

Ask yourself:

Where did I learn about sex and gender?

Are there aspects of gender and sexuality that make me uncomfortable?

How have gender norms changed over the history of my culture?

Dive Deeper

Indigenous history and human rights

Discover the stories of Indigenous people and communities. Learn about Canada's history of colonialism and genocide. Reflect on how we can collectively work towards reconciliation.

References

- Examples of major scholarly interventions in this area include: Gregory D. Smithers, Reclaiming Two‐Spirits: Sexuality, Spiritual Renewal, and Sovereignty in Native America (Boston: Beacon Press, 2022); Mark Rifkin, When Did Indians Become Straight?: Kinship, the History of Sexuality, and Native Sovereignty (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011); Sarah Carter, The Importance of Being Monogamous: Marriage and Nation Building in Western Canada to 1915 (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2008). Back to citation 1

- This table is drawn from Chelsea Vowel, Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis & Inuit Issues in Canada (Winnipeg: Highwater Press, 2016). Back to citation 2

- Ma-Nee’s powerful story is told by Ma‐Nee Chacaby with Mary Louisa Plummer, A Two‐Spirit Journey: The Autobiography of a Lesbian Ojibwa‐Cree Elder (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2016). Back to citation 3

- For a classic study, see: Martin Cannon, “The Regulation of First Nations Sexuality,” Canadian Journal of Native Studies, XVIII.1 (1998):1–18. Also see: Carter, The Importance of Being Monogamous. Back to citation 4

- For a comprehensive account of these and related issues, see: Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls: Volume 1a (Canada, 2019). Back to citation 5

- Many such contradictions appear in Emily K. Hobson, Lavender and Red: Liberation and Solidarity in the Gay and Lesbian Left (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2016). Back to citation 6

- A scholarly account of this period is provided in Scott Morgensen, Spaces Between Us: Queer Settler Colonialism and Indigenous Decolonization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). Back to citation 7

- Here Myra Laramee discusses this moment in her own words: “Two‐Spirit: A Movement Born in Winnipeg,” City of Winnipeg, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eu4xNUq2hGE. Back to citation 8

- This point is powerfully articulated in Qwo‐Li Driskill, “Doubleweaving Two‐Spirit Critiques: Building Alliances between Native and Queer Studies,” GLQ, 16.1–2 (2010). Back to citation 9

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Scott de Groot. “What Is Two-Spirit? Part One: Origins.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published March 26, 2024. https://humanrights.ca/story/what-two-spirit-part-one-origins