It was the summer of 1969, and all over the world, people were taking to the streets, singing songs of resistance. “We Shall Overcome” we sang in my west coast Canadian town, marching to the courthouse downtown, bracing antiwar banners against a buffeting wind.

The Amchitka Campaign

How music boosted the beginning of Greenpeace and saved the day

By Barbara Stowe

Published: January 5, 2024 Updated: February 23, 2024

Tags:

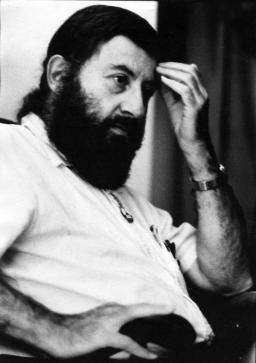

Credit: Greenpeace, photograph by Robert Keziere

Story text

Music was the thing.

To tell it like it was, we needed music.

Only the U.S. president and his men couldn’t hear the music, the beating heart of the times. They were deaf to cries for peace, stuck in old, ruinous ways. On Amchitka Island, so far off the coast of Alaska it was almost in Russia, their hired hands dug deep into colonized Indigenous soil, making nests for hydrogen bombs. Seismologists said underground blasts in this tectonically volatile region could potentially initiate earthquakes and send tidal waves around the whole Pacific Rim.

President Nixon and his men blocked their ears.

Nor did they care that Amchitka was a dedicated wildlife sanctuary. When my lawyer/activist father, Irving Stowe, heard that sea otters were washing up dead on the beaches of Amchitka Island, their eardrums split by pre‐trial blasts, he was incensed. He stormed off to the U.S. Consulate in downtown Vancouver with a handwritten petition and stood outside, soliciting signatures. Then he called his friend Jim Bohlen.

“Jim,” he said, “we have to do something!”

The next morning, Jim and his wife Marie came over for a breakfast meeting with my father and mother (Dorothy). They started a small group to agitate against the blasts — the “Don’t Make a Wave Committee.” Jim was a visionary engineer; Marie, a respected nature illustrator; Mum, a psychiatric social worker. They were all Quakers, and as more people joined, the burgeoning group was guided by Quaker principles of pacifism, speaking truth to power, and bearing witness.

Meanwhile, environmental columnist Bob Hunter was writing in the Vancouver Sun that the U.S. was playing “a game of Russian roulette with a nuclear pistol pressed against the head of the world.” He started coming to meetings. So did Ben and Dorothy Metcalfe, another two powerful journalistic allies. More people joined, all bringing unique passions and skills to the cause.

But one question kept frustrating them: How could anyone bear witness to atomic tests on such a far‐flung island?

In February 1970, Marie came up with the answer. “Why not sail a boat up there?”

This idea sang to an idealistic group of change‐artists. Only, what would it cost?

“If the cause is right, the money will come,” said Marie.

One night, as a meeting came to an end, Dad flashed a peace sign at a young community organizer, Bill Darnell, who was headed out the door. “Hey, Bill!” he called, “Peace!”

In his deep bass voice, Bill came back with: “Let’s make it a green peace.”

Dad phoned Bill up the next morning, very excited. “The peace movement and the environmental movement,” he said, “this puts it all together!”

“That’s what we should call the boat, when we get one,” Jim declared at the next meeting. “The Green Peace.”

Paul Noonan, Marie Bohlen’s son from a previous marriage, designed a button that came back from the printer with no space between the two words, and we all tramped out to stand on street corners, hawking Greenpeace pins for 25 cents apiece.

But button sales wouldn’t raise the thousands of dollars we needed to charter a boat.

Meanwhile, the U.S. announced it would explode the biggest underground nuclear test in history on Amchitka Island, in the fall of 1971.

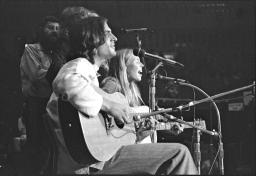

Dad decided to organize a benefit concert. He’d never organized a concert before, and most of us were skeptical — until activist singer/songwriter Phil Ochs signed on. And Canadian folk/rock band Chilliwack agreed to play. And when 28‐year‐old superstar Joni Mitchell joined the bill, we were all psyched! As we plastered the town with posters, Dad booked one of Vancouver’s biggest concert arenas, the Pacific Coliseum, for October 16, 1970.

It didn’t hurt that Joni Mitchell offered to bring James Taylor.

The concert sold out.

But as October began, a dark and dire note intruded. A militant wing of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) — a Québec separatist group — kidnapped two dignitaries, and at 4 a.m. on the day of the concert, Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act. Tanks rolled through the streets of Montréal, civil liberties were suspended nationwide, and we were sure the powers‐that‐be would cancel the concert.

We were wrong. Some greater good vibe was operating, and Phil Ochs stood under the hot stage lights muttering “not every day you get to play in a police state” before launching into “Rhythms of Revolution.”

Chilliwack got us dancing. “If there’s no audience,” they sang, “there just ain’t no show.” I turned around to see the whole Coliseum singing and swaying in unison. And then Dad came on to draw the door prize, pulling a ticket out of a hat. The prize? A free ride on the Greenpeace boat to Amchitka!

This was a dubious prize. Dubious because the voyage of the Greenpeace looked like a suicide mission: freak fall storms in the Bering Sea; radiation venting from the bomb shaft; an underwater quake generating a tsunami with the boat right in its path — the risks were terrifying. And still, people who’d never protested anything in their lives were sending the Committee letters, begging to crew. As if a protest voyage could bring enough public pressure to bear on stone‐deaf politicians to make a difference.

We were betting on it.

And music was the key. James Taylor soothed our souls with his Southern drawl, Joni’s singular soprano voice soared into “Chelsea Morning,” and we clapped madly when she called James back to croon “Mr. Tambourine Man” with her. They were in love and playing for free.

At 1 a.m. the house lights came back up and we all trooped out of the Coliseum. Together, we’d raised almost $18,000 — just enough to charter the fishing boat of one Captain John Cormack: the only man brave enough—crazy enough—and (rumour had it) financially desperate enough to take on this mad mission.

On September 15, 1971, the Greenpeace set sail from Vancouver’s False Creek.

It never made it to Amchitka.

The U.S. Coast Guard turned Cormack back on a technicality. All hope seemed lost. But the world jeered at deaf authority and took to the streets. In Tokyo, Japanese hoisted signs that said, “Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Amchitka.” Here at home, my brother Bob helped lead a 10,000-strong high school student walk‐out to the U.S. Consulate. The public was so enraged Dad was able to raise enough money in just a few weeks to charter a second ship, a former Canadian minesweeper the group dubbed the Greenpeace Too.

It was steaming towards Amchitka on November 6 when Nixon gave the go‐ahead, and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission exploded the massive blast.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game guesstimated as many as 2,000 sea otters were killed.

The world mourned Nixon’s hubris.

Several months later, however, the U.S. quietly cancelled the test series. Eight bomb cavities had been drilled but only three were ever used. The people had spoken, and their voices had been heard.

No one disputed that the two Greenpeace boats had played a pivotal role in this victory.

Or that music had saved the day.

Sources

The author would like to acknowledge two books as helpful sources for this piece of writing: Dean W. Kohlhoff’s Amchitka and the Bomb and Rex Weyler’s Greenpeace: The Inside Story.

See more at the Museum

Dive Deeper

Stories that move us Beyond the Beat

Historical and contemporary stories of how music, musicians and audiences move society towards greater justice.

Beyond the Beat: Music of Resistance and Change

Music can be a powerful force for social and political change. Explore stories of artists who have used their voices and platforms to advance causes and advocate for change.

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Barbara Stowe. “The Amchitka Campaign.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published January 5, 2024. Updated: February 23, 2024. https://humanrights.ca/story/amchitka-campaign