One must wonder how, after 50 years, can hip‐hop still be a vibrant youth culture with global reach? Those who say they “don’t like rap,” yet enjoy Shad’s cerebral rhymes or the Dream Warriors’ jazz‐infused chart‐topping tracks, remind us of the enduring appeal of hip‐hop music and culture beyond its negative press.

Beyond the Beats and Rhymes Is Life

Hip hop’s four elements speak truth to power around the world

By Mark V. Campbell (DJ Grumps)

Published: January 23, 2024 Updated: February 23, 2024

Tags:

Photo: Colin Lloyd, Unsplash

Story text

The brash and bold rhymes found in the art of rhyming, one of hip-hop’s four foundational elements [1], hold massive appeal for youth, equipping them with a voice and the ability to craft their identities through their multi‐elemental stylistic interpretations. In hip‐hop culture, the way that you “rock” defines your status. And rocking a microphone, rocking a crowd, or rocking a backwards cap are all activities any young person can attempt, regardless of ethnicity, nationality or neighbourhood, to garner some love from their peers and local community.

When one’s peers and community show love, this often mitigates (too often temporarily) the punishing class‐based and race‐based stigmas that maintain social inequalities. This is why hip‐hop culture “can’t stop and won’t stop” – the culture helps young people develop a value system that does not reproduce the vicious social inequalities that form the basis of Western cultures. The repetitive boom bap of hip-hop’s kicks and snares, alongside the rhythmic use of the voice, have been replicated around the globe, making hip‐hop culture a worldwide phenomenon five decades after its inception.

There is no doubt that issues of social justice are embedded in the rhymes that document, critique and disseminate what life is like on the margins of mainstream society. One could turn to hip‐hop music born in Paris’s banlieues or Rio de Janeiro’s favelas or Canada’s reserves – the results will be similar because protest and resistance are embedded into hip‐hop culture.

To explore the lineages of protest and critique in hip‐hop music, lyrics are a good starting point, but not the only entry point. Hip‐hop lyrics consistently perform verbal gymnastics, stretching metaphors, uncovering similes, while making good use of repetition, double and triple entendres. All this, while witnessing, documenting and celebrating human life in nuanced ways.

When I’m cruising in my Volvo, cops harass me. They never ride past me, they hound me like Lassie.

Lyrically, it is easy to identify and feel the way hip‐hop has spoken truth to power. While hip-hop’s beats keep us moving, it is the lyrics that poignantly illuminate the social realities of those involved in the street culture that begat hip‐hop. Grandmaster Flash and the Furious 5 vividly captured the realities of neoliberal NYC after its 1975 fiscal crisis, with “The Message”:

Broken glass everywhere. People pissing on the stairs, you know they just don’t care.

Globally, the message was audible and legible, and it seeped into the consciousness of future fans thousands of miles away from New York City.

Lyrical words of protest and the empowerment of those on the margins can be gleaned and experienced via a cassette, vinyl, radio program or stream. The items included in this vast exhibition are but a glimpse into how we might understand aspects of hip‐hop music as contributing to legacies of protest music from across a wide range of musical genres. These artifacts are not meant to elaborate all of hip-hop’s histories of protest. Rather, they are designed to convince us that there is something more than entertainment value embedded within popular music cultures.

You would rather have a Lexus or justice? A dream or some substance? A Bimmer, a necklace or freedom?

Digging deeper, beyond hip-hop’s elaborate, sophisticated lyrical acrobatics are the other foundational elements of hip‐hop culture. Practitioners of hip-hop’s elements know that resistance to form is deeply foundational to the many artistic innovations birthed by the culture. From graffiti to breaking, turntablism to beatboxing, the vastness of artistic innovation embedded within hip‐hop culture is also home to signs of protest, displeasure, critique and dissonance. While lyrics can be experienced via any streaming platform, the energy of a cipher or battle necessitates an in‐the‐flesh experience.

Hip-hop’s lush lyrical maneuvers are seductive, yet they also remind us that this culture is an open signifier. When bad means good, and when an old song is sampled anew, this says that the culture is home to multiple significations. Songs will tell us:

“You must learn” - KRS‐One, 1989

or

“when we struggle day to day let us not forget our power” — Progress, 2011

or

“Fuck the police.” — Jay Dee, 2001

In this culture, as emcees spit conscious and enlightening rhymes, and as breakdancers remove their crutches or overcome arthrogryposis, a neuromuscular disorder (peace to Bboy Lazylegz and Bboy Haiper) to devour a funky breakdown, there is no one singularity – norms are constantly disrupted and destroyed by this open signifier called hip‐hop. Turntablists take two vinyl records and transform them into musical notes, while a visually impaired DJ enters the battle and blows some minds (mine included – peace to Cosmic Kev). The culture knows that, irrespective of race, creed, location or physical ability, you gotta have style.

Style rules supreme

As a culture, hip‐hop has shown itself not only to be the genius of African American and Latino youth, but also a global template for voicing protest and denouncing political corruption (ask Morocco’s monarchy). Hip‐hop culture has proven to be a template of human value and worth, far beyond the limited and limiting constructs of race and class – as well as the hierarchically arranged labour market. The way that one exudes their own style, whether it be physically through dance, visually through graffiti or sonically through DJing, allows one to live a life of value, even when their host society refuses to imbue value upon the underemployed, the unhoused or the accented speech of a newly migrated individual.

As some artifacts in Beyond the Beat demonstrate, there is life attached to hip‐hop culture. It is not simply improvised rhymes or bold fashion statements. This life is not easily discernible beyond the hype, the streams, the outrage and the conspicuous consumption. Beyond the beats and the rhymes, the daily life of living hip‐hop culture comes into sharper focus when we dig into the social context and, at times, damning realities. There, we find innovative artists challenging not just bias, racism, sexism and classist social structures, but the forms of human lives deemed worthy of social inclusion. For example, for multilingual newcomers in a Francophone province such as Quebec, this challenge manifests itself in living a life that exalts the multiplicities of linguistic inheritances, innovatively weaving them into one another in unpredictably exciting ways.

Nomadic Massive’s context on the front lines of Canada’s linguistic battleground in Quebec critically stimulates their music and art. Consisting of, at times, up to ten members, and traversing the globe, this multilingual hip‐hop supergroup easily rises above Canada’s “multiculturalism within a bilingual framework.” Theirs is a hip‐hop that operates as an open signifier. Their art doesn’t simply resist – it persists in its resignification of how our sociality ought to be. The multiplicities of language ooze out of every stanza and rhyming couplet, making their form of resistance an active way of being, a praxis of living a multilingual and multihyphenated reality. Their uniqueness has yet to be replicated in the Canadian hip‐hop scene, where most multilingual rhymes are bilingual, or at most English, French and an Indigenous language, not splashed out with layers and layers of Spanish, Arabic and Patwa finishing various couplets and stanzas. Check the lyrics by Meryem Saci, as she flips a verse on Nomadic Massive’s track “Any Sound”:

A3tini l’beat/a3tini l’rythme/Ou khalini n'tayeb un hit/Ki n'khalatte toutes les épices/Fills ya unlike any food you eat/J’assaisonne les amnésiques/Avec la mémoire de l’Afrique/Give you something you can feel/Peu importe ton taux de mélanine/See my philosophy/Can’t pull the roots out of me/And it’s spreading out of space/No counterfeit/Armini anywhere fi had dounya/Ma tat9ala9ch a3liya/I’m like a chameleon, camouflée /Majestic without a crown/With this message I’m steady bound/Not a diplomat, still welcome on each and every ground/Ways of the nomad/I wave no flag/Humano universal/Ripping any sound

The artists in Nomadic Massive live a specific relationship to justice, many of their members being deeply enmeshed in community and public education in their hometown of Montréal. They explode our frameworks to make language a welcoming and inclusive endeavour, moving beyond preservation to the deeply entangled and intersecting realities of language. Nomadic Massive doesn’t just lyrically represent; the artists live in relation to their rhymes, their cultures and their linguistic heritage. Member Tali astutely sums up this supergroup’s impact when she says, “[Nomadic Massive] serves as a big up to everyone that has been othered in this province.”

Put it in perspective, the world is divided in two. Those who will fight and those who will silently give up hope. (Translation)

Still Tho

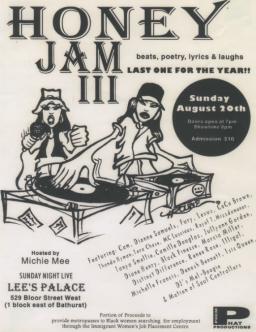

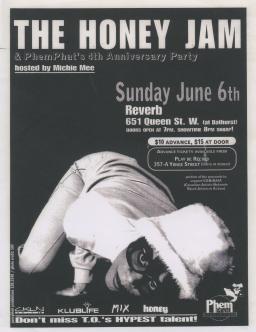

Offstage, in a different province (Ontario) and wildly different context, justice, equity and inclusion are still in a showdown with patriarchy. Over more than a quarter century of putting on an all‐female showcase, PhemPhat Productions, the team behind the Honey Jam, never lost sight of the importance of creating stages for women. In these annual affirming events, Ebonnie Rowe programs a live showcase of female performers from a variety of musical genres.

While Ebonnie Rowe may not be a practicing hip‐hop artist, her life has been focused on building stages where the rights of women in the music industry can be in the foreground, as our society still aims for gender parity in film and in music festival programming.

After decades of performing and promoting, the Honey Jam boasts an impressive array of alumni, from Jully Black to Nelly Furtado, to Haviah Mighty to Melanie Fiona and more. Rowe has clearly dedicated her life to supporting women on stage, making Honey Jam one vital component in the fight for gender parity from 1995 to the present. PhemPhat Productions, quite literally, has been setting the stage for women in all music genres to take their place in the music industry and actively pursue their rights as artists to live a creative life.

The life that exists beyond the beats and the rhymes is often neither on stage nor in the media spotlight. When the flashing lights are absent, this doesn’t mean the journey towards justice isn’t happening. In this 50th year of hip‐hop culture, while we select artifacts to uncover and stimulate new stories and forgotten his/herstories, there remains, beyond material items, a continued relationship between justice, equity and harm‐reducing modalities of living in this world.

So what the new Black activists do for our freedom. Is just being them.

Beyond the Noise

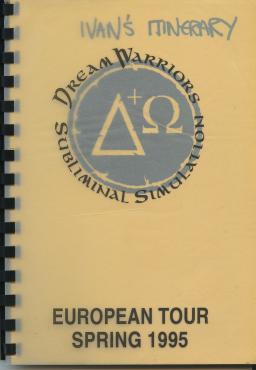

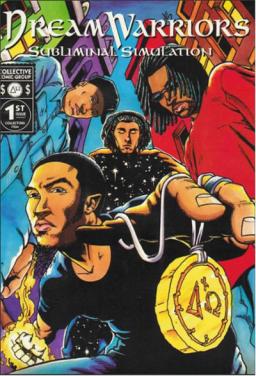

For some artists, significant work happens beyond the limelight. The Dream Warriors, one of Canada’s first global successes in the rap music industry, made music that was known for its jazzy and experiential vibes, not necessarily a “fight the power” vibe. According to one journalist, their first two singles, “Wash Your Face in My Sink” and “My Definition of a Boombastic Jazz Style,” “swept through the British Top 20 with real style and panache.”[2]

The Dream Warriors, global stars in 1995, took Europe by storm, selling out a 27‐date tour including cities such as Paris, Copenhagen, Milan and Brussels. While American suburban tweens and teens were enthralled by NWA’s brand of gangsterism, the Dream Warriors presented a jazzier and more melodic Afrofuturistic sound that did not cater to the white racial imagination (see Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination). Their form of inclusion, by attempting to widen the terrain of what is hip‐hop music, can easily be understood as a form of protest – one that advocates for the celebration of Black life beyond the gaze of dominant society.

For the Dream Warriors, it was their clothing, video set, comic books, accessories and choice of samples that distinguished them as existing on another plane of consciousness. Journalists quickly noted the Quincy Jones sample on their lead single and the Count Basie sample on their second single. By naming their debut album And Now the Legacy Begins, the Dream Warriors sent a layered and deeply complex signal that they understood their artistic mission to exceed the boundaries of the contemporary music industry. The Dream Warriors widened the frame of hip‐hop, refusing to let negative imagery and lyrics dominate the landscape of hip‐hop music as its popularity exploded in the early 1990s.

As hip‐hop music was entering mainstream America in the middle of the 1990s, there was another emergence into the mainstream of music world in Canada. When War Party’s “Feeling Reserved” received national rotation on MuchMusic, it became vividly clear that hip‐hop culture can be and is more than just dope rhymes, ill beats and hot tracks.

Rex and Cynthia Smallboy, Karmen and Bryan Omeosoo, Ryan Small and Tom Crier were the group’s members and their music video toured us through life on a reserve in Canada. With stunning ethnographic detail and deftly executed puns, similes and metaphors, War Party’s version of reality rap was the furthest thing from NWA’s gangsterism. Yet, it was the realest perspective – and one that did not make suburban white American teens flock to the store. War Party illuminated for the majority of non‐reserve dwellers the realities of rez life for Indigenous people – a far cry from the highly commodifiable visuals of violence, apathy and crude stereotypes that plague much of the white racial imagination.

Speaking truth to power not only opened the doors to future generations of Indigenous emcees, it also held space for truth speakers and artists such as Eekwol, Samian and Drezus. Speaking truth has brought us the music that moves us beyond the beats and the rhymes. Hip‐hop artists, such as many of those mentioned and quoted here, encourage us not only to “fight the power” or resist, but also to cultivate lives which actively value justice, inclusion and social equity.

Life beyond the beats and the rhymes, even if obscured by questionable media representations, consistently involves the work of oppositional thinking and a resistance to the behaviours which only serve to reify the structures of oppression that circumscribe some human lives. Instead, our lives, as hip‐hop heads, are innovatively designed to create value, to garner love from our communities and to exist as open signifiers who challenge and rewrite the acceptable forms of what it means to be human, artistic and creative.

In an era when efforts to preserve popular music are focused on rock, country and punk, hip-hop’s 50th anniversary is an excellent time to examine the artifacts this dynamic youth counterculture produced. Sitting with these items brings us a bit closer to understanding the ways in which protest reverberates out of hip‐hop music and moves through all of the culture’s elements, including the praxis that defines our lives.

Discography

Big Daddy Kane, “Another Victory,” Cold Chillin Records, 1988.

Dead Prez, “It’s Bigger than Hip‐Hop,” Loud Records, 1999.

Dream Warriors, And Now the Legacy Begins, Island Records & 4th and Broadway, 1991.

Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, “The Message,” Sugarhill Records, 1983.

KRS‐One, “You Must Learn,” Jive Record, 1989.

Jay Dee, “Fuck the Police,” Up Above Records (Vinyl), 2001.

Nomadic Massive, “Any Sound,” Coop Les Faux‐Monnayeurs, 2016.

Nomadic Massive, “Quoi Te Dire?” 888 Records, 2019. Progress, “As I Reflect,” Independent, 2011.

Shad, “(Brother) Watching,” Black Box Recordings, 2007.

War Party, “Feeling Reserved,” Warparty Recordings Company, 2002.

See more at the Museum

Dive Deeper

Stories that move us Beyond the Beat

Historical and contemporary stories of how music, musicians and audiences move society towards greater justice.

Beyond the Beat: Music of Resistance and Change

Music can be a powerful force for social and political change. Explore stories of artists who have used their voices and platforms to advance causes and advocate for change.

References

- Rapping alongside graffiti, DJing and b‑boying (aka breakdancing) form the four foundational elements of hip‐hop culture. Back to citation 1

- Hewitt, Paolo. Dream Warriors: Don’t Dream It, Be It! Select: pp. 48–52 Back to citation 2

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Mark V. Campbell (DJ Grumps). “Beyond the Beats and Rhymes Is Life.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published January 23, 2024. Updated: February 23, 2024. https://humanrights.ca/story/beyond-beats-and-rhymes-life