Presenting the "Four Freedoms" exhibit in our Turning Points for Humanity gallery.

Four fundamental freedoms

Freedom of speech, freedom of belief, freedom from fear and freedom from want

By Jeremy Maron

Published: June 21, 2017

Tags:

Photo: CMHR, Stephanie Chipilski

Story text

In his January 1941 State of the Union address, American President Franklin D. Roosevelt articulated four fundamental freedoms that everyone in the world ought to be able to enjoy – freedom of speech, freedom of belief, freedom from fear and freedom from want. While the United States had yet to enter the Second World War at the time (and would not until the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941), Roosevelt’s appeal to these freedoms as universal was aimed at encouraging the country to support the Allied war efforts against Nazi Germany, whose totalitarian campaigns of aggression and genocidal annihilation were the antithesis of these ideals of universal freedoms.

In 1948, in the aftermath of the unimaginable human cost of the Second World War, these four freedoms were again articulated, this time in the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The highest aspiration of “the common people” was declared to be a world where everyone could enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want.

But of course, the decades since have shown that the implementation of these ideals into reality is challenging, as violations around the world – including in Canada – continue to strip or prevent the universal enjoyment of the four freedoms, as well as the other human rights articulated in the UDHR.

The “Four Freedoms” exhibit uses objects to tell four distinct stories from different parts of the world, which convey the importance of the four freedoms, and the effects on people’s lives when they are denied. These stories also convey how rights and freedoms are fragile, and that even where they may exist in some capacity, vigilance is required to ensure their continued protection.

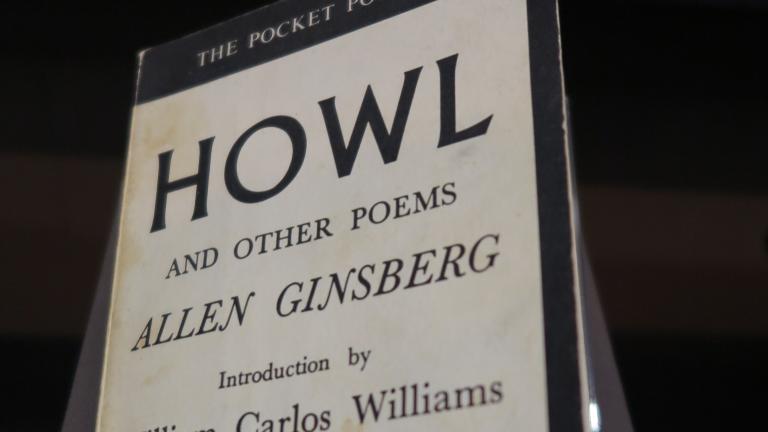

The element on Freedom of Speech is represented through a signed edition of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems. In 1957, Ginsberg’s poem “Howl” was the subject of an “obscenity trial” in San Francisco, on the basis that its descriptions of sex and drugs were obscene. The case raised important questions about the extent to which expression could (or should) be limited by powers of the state. In the end, the judge ruled the poem did not constitute obscenity, and stated that free speech must be protected “if we are to remain free, both individually and as a nation.” The Howl trial was a landmark case regarding free speech and expression.

The importance of Freedom of Belief is illustrated through pages and fragments from a burned Urdu‐language Bible damaged in a 2013 suicide bombing at the All Saints’ Church in Peshawar, Pakistan – a state where religious minorities such as Christians, Hindus and Ahmadi Muslims face routine discrimination, despite a constitution that aims to guarantee religious freedom. The Bible pages on are loan to the Museum from One Free World International, an organization that advocates on behalf of persecuted religious minorities in many parts of the world.

The Freedom from Fear component is conveyed through a home radiation detection kit from the Cold War – a period of political and military tensions, primarily between the United States and the Soviet Union, from the late 1940s to 1991. During this time, the two superpowers competed with each other to amass nuclear weapons in an “arms race.” The threat of nuclear war contributed to a culture of fear on both sides of the conflict. The radiation kit – designed to detect fallout radiation levels in one’s home in the aftermath of a nuclear attack – is on loan from the Diefenbunker: Canada’s Cold War Museum.

.jpg?itok=7Aj9CQPf)

The element on Freedom from Want is illustrated with a prop bag of flour – a seemingly mundane object that is used as an entry point to tell the critically important story about food insecurity in northern Canada. Food prices in the North are far higher than in the rest of Canada due to factors including higher costs for transporting goods and operating stores in remote locations. For example, in 2016, a bag of flour similar to the one displayed cost on average $5 in the rest of Canada, while in Nunavut the average price was $13.70. The difference is even more striking when one considers that the “rest of Canada” price had dropped from the 2015 average of $5.03, while in Nunavut the average had increased from $13.60. High costs like this in the North mean that residents often lack access to sufficient affordable and healthy food, which has led to medical problems in many northern communities and families.

These objects, and stories they convey, offer profound visual reminders of the challenges of translating ideals of universal human rights into reality. But these challenges do not mean the work is not worth doing, or that the situation is hopeless. Immediately adjacent to this display in Turning Points for Humanity are interactive digital books that carry stories of people and groups working at grassroots levels to try to ensure that the ideals of the four freedoms and the UDHR are enjoyed by all people in their lived experiences, despite the challenges.

We hope that the compelling yet sobering content in the “Four Freedoms” exhibit will inspire our visitors to consider human rights as both valuable and vulnerable, and to reflect on steps they can take – large or small – to be vigilant in the protection, promotion and enhancement of human rights in their own spheres of influence.

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Jeremy Maron. “Four fundamental freedoms.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published June 21, 2017. https://humanrights.ca/story/four-fundamental-freedoms