The freedom to express ourselves through language is a fundamental human right. Whether with friends or family, communicating our thoughts, ideas, wishes and needs with those around us is key to basic survival. Language is also a vehicle for participation in community and cultural life.

Language rights are human rights

Exploring Canada’s official languages framework

By Rémi Courcelles

Published: September 6, 2019

Tags:

Photo: Canadian Press, Francis Vachon

Story text

Take a moment and ask yourself: what would your life be like if you were prevented from expressing yourself in your own language? How would you get by? How long would it take before you felt frustrated, or lonely? In Canada, we all have the right to express ourselves in our own language in our private life, whether at home, online or in a public setting. However, when it comes to communication with government and public institutions, the state has the right to designate official languages. In this article, we explore Canada’s complex linguistic rights framework.

Canada’s multilingual heritage

Language has always played a crucial role in shaping diverse identities in Canada. The legacy of European settlement and colonial expansion has made English and French both the dominant and minority languages in various parts of the country. More than 60 Indigenous languages are still spoken all over the continent1, although many of them are endangered due to a decline in the number of fluent or first‐language speakers. In addition, numerous waves of immigration from around the world have increased the presence of many other global languages in Canada.

Designating official languages

In 1969, Parliament passed a law making French and English Canada’s official languages. Through the Official Languages Act, the Canadian government committed itself to deliver its services in both official languages. Anglophones and Francophones, most of whom are unilingual, could now communicate with federal departments and agencies in the official language of their choice.

- The Province of New Brunswick declared itself an officially bilingual province in 1969, when it passed its own Official Languages Act. This made New Brunswick the only officially bilingual province in the country, which it remains to this day.

- In the North, French and English are official languages in all three territories. The Northwest Territories made nine Indigenous languages co‐official in 1988, while Nunavut made the Inuit language co‐official in 2008.

- Manitoba and Quebec are officially unilingual provinces. However, they both offer important constitutional protections for their official‐language minority populations.

Forest and Blaikie: Pivotal minority-language cases in Manitoba and Quebec

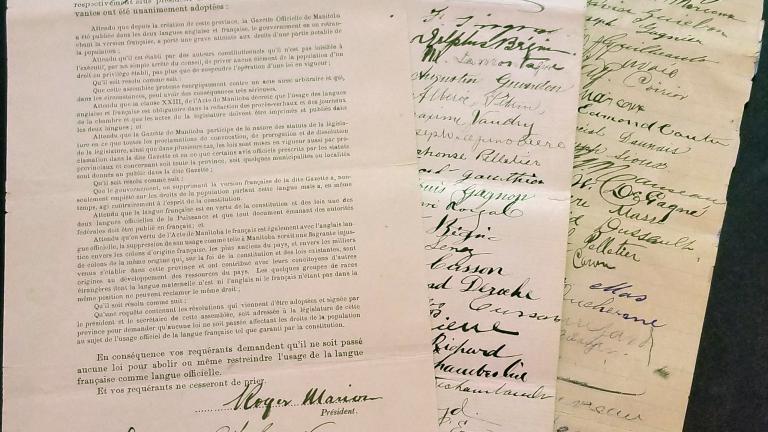

Georges Forest was a child when he learned from his grandmother about the linguistic rights that were taken away from Manitoba’s French‐speaking population in 1890. In 1870, Métis leader Louis Riel had successfully negotiated Manitoba’s entry into Canadian Confederation as a bilingual province where linguistic and religious rights were guaranteed. Section 23 of the Manitoba Act of 1870 states:

Either the English or the French language may be used by any person in the debates of the Houses of the Legislature, and both those languages shall be used in the respective Records and Journals of those Houses: and either of those languages may be used by any person, or in any Pleading or Process, in or issuing from any Court of Canada established under the British North America Act, 1867, or in or from all or any of the Courts of the Province. The acts of the Legislature shall be printed and published in both those languages.

Despite these guarantees, when the number of newcomers coming mostly from Ontario swelled from a few hundred to some tens of thousands, the new Manitoban government moved to swiftly adopt An Act to Provide that the English Language shall be the Official Language of the Province of Manitoba. French‐speakers who had resisted joining Confederation on Canada’s terms only 20 years before sent petitions to the provincial government demanding that their language remain an official one. But this was to no avail. Manitoba became officially unilingual in 1890.

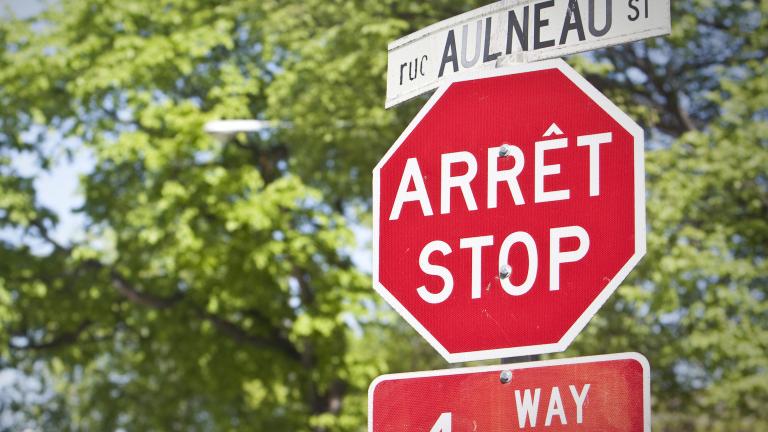

In 1976, Georges Forest received a parking ticket written in English only in the Francophone community of St. Boniface. This, despite a 1971 provision in the City of Winnipeg Act granting that all communication in the community was to remain bilingual. Forest decided to dispute the charges in court. When it was ruled that Manitoba’s 86‐year‐old unilingual language law took precedence over the City’s bilingual guarantees, Forest knew this was his chance to challenge the legality of what he found to be an unjust law.

Manitoba can now be the birthplace of a new Canadian identity.

Manitoba’s language law had already been declared unconstitutional on two occasions. In 1892 and again in 1909, the courts ruled that the Manitoba Act formed part of the Canadian Constitution and therefore could not be disregarded by the provincial government. However, on both occasions, the Province simply ignored the ruling. Manitoba remained a unilingual province, violating the constitutional rights of Francophones for decades more and instilling a sense in the Franco‐Manitoban community that mobilizing to defend their constitutional rights could anger the Anglophone majority and lead to a further loss of rights.

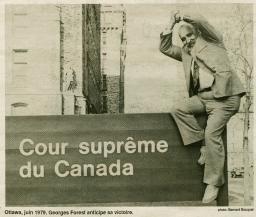

Undeterred, Forest took the cause to court, filing his appeal and other court documents in French as the Manitoba Act allowed him to do. The matter went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Forest’s case was not the only one making its way through the court system. Around the same time, in Montréal, Peter Blaikie and two other lawyers were challenging the Province of Quebec’s new Charter of the French Language, which made French the only official language of the legislature and the courts. In fact, section 23 of the Manitoba Act was a virtual copy of section 133 of Canada’s constitution, which gave Quebec Anglophones the same linguistic rights as Franco‐Manitobans. Much like Forest, the lawyers argued that the Province of Quebec didn’t have the right to override the constitution unilaterally.

Given the similarity between the cases, the Supreme Court delivered both judgements on the same day. On December 13, 1979, in unanimous decisions, the court ruled that the provinces could not infringe on the constitutional rights of the linguistic‐minority populations without first changing the Constitution itself. This proved a high threshold, given the growing consensus around the bilingual and bicultural character of Canadian identity at the time.

For many, many years, we got along without anyone complaining about it, and I think that a lot of people probably thought that Georges Forest was being a bit fussy in complaining about it, but it appears it led to a very important constitutional decision.

After the rulings, Quebec Premier René Lévesque immediately called a legislative all‐nighter to make sure that all laws passed in the two years since the adoption of Quebec’s Charter of the French Language were translated into English. The Manitoban government, on the other hand, made clear that it would only go so far as required by law. It would take another five years before Roger Bilodeau, a Franco‐Manitoban lawyer who received an English‐only parking ticket six months after the Supreme Court’s 1979 ruling, would push government to ask the highest court whether all the unilingual laws passed since 1890 were valid.

Video: Roger Bilodeau – Defending language rights in Manitoba

In the end, the Supreme Court declared all laws adopted since 1890 in English‐only as invalid. However, to avoid a state of chaos and lawlessness, the court allowed the laws to remain in force until all the laws were translated, re‐enacted, printed and published in French and English. Manitoba and Quebec today offer the same constitutional protections for their official‐language minority populations.

Linguistic rights in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

In the midst of these pivotal Supreme Court cases, Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau was negotiating the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms which would become the cornerstone for human rights protections in Canada. The Charter forms part of Canada’s new Constitution, which means no law can go against it. It was proclaimed by Queen Elizabeth II on April 17, 1982.

The Charter includes six language rights, which are divided in two parts. Sections 16 to 22 relate to Canada’s official languages and reinforce their equal use, status, rights and privileges in both the federal jurisdiction as well as in New Brunswick. Section 23 offers a new set of educational rights for official‐language minorities throughout the country.

Official languages in Canada today

More than 50 years after the passing of the Official Languages Act, 1969, Canada’s official languages face new challenges. Despite a 50 percent increase in bilingualism since 1969 and a record number of youth who are studying French or English as a second language, the growth rate of Canada’s official‐language minority communities is slower than overall population growth. Two million Canadians make up these official‐language minority populations – 1 million Francophones outside of Quebec and 1 million Anglophones in Quebec. While these communities have never been bigger, each one faces its own realities and challenges.

The French language remains in a vulnerable position nationally. Despite Quebec’s strong Francophone majority and the successes of the Official Languages Act, calls for more support are still being heard from Francophone communities outside of Quebec. Inside la belle province, the Charter of the French Language (also known as Bill 101) has provided important supports for the vitality of the language. At the same time, English‐speakers in Quebec often feel that their identity isn’t understood or valued by the province’s Francophone majority.

The modernization of the Official Languages Act has been a hot topic of conversation throughout the country. In March 2019, the Government of Canada announced it would be reviewing the law, which was last updated in 1988. Consultations were held and a summary report was published in June 2019. It shows that Canadians want the Act to be modernized in a way that protects existing rights while supporting the vitality of Canada’s official languages.

Reconciliation in action: The case for Indigenous languages

Indigenous languages face an unmatched level of vulnerability in Canada. Indigenous peoples faced systematic discrimination and cultural repression for decades, including through the genocidal practices of Canada’s Indian residential school system. Indigenous leaders were also largely ignored during the consultations on Canadian unity that led to the passing of the Official Languages Act in the 1960s.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada made 94 Calls to Action to redress this legacy and to advance the process of Canadian reconciliation. These included a call for the federal government to pass a law supporting the preservation, revitalization and strengthening of Indigenous languages, as well as the creation of a commissioner for these languages. This piece of legislation became law in June 2019. Some have even called for Indigenous languages to also be designated as official languages, including in the Calls for Justice of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

2019 was also the International Year of Indigenous Languages, as declared by the United Nations. Its objective was to focus global attention to the issues facing Indigenous languages, which make up more than 4,000 of the estimated 6,700 languages spoken around the world. It also aimed to mobilize international cooperation in celebrating, supporting and revitalizing these languages, and to achieve the goals set out in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, a non‐binding declaration of principle grounded in human rights standards. In 2016, Canada announced its full support for this declaration.

Expressing ourselves in our own language is a fundamental right

Human rights are rights that each and every one of us possess by the simple fact that we are human beings. Given the close link between language, culture, identity and participation in community life, the right to express ourselves in our language is a fundamental right. Its fulfillment allows us to achieve our fullest potential, both as individuals and as a society.

Ask yourself:

What role does language play in the survival of my identity and culture?

What is government’s responsibility in ensuring language rights are respected?

How can we better protect Canada’s official languages?

1 For more information, see “Mapping Indigenous Languages in Canada”.

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Rémi Courcelles. “Language rights are human rights.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published September 6, 2019. https://humanrights.ca/story/language-rights-are-human-rights