The exhibition Mandela: Struggle for Freedom is opening at the Museum in June 2018. It shares the story of Nelson Mandela and his struggle against apartheid, a system of white supremacy that existed in South Africa. Curator Isabelle Masson, along with many other staff members at the Museum, has been working hard to create Mandela and get it ready for opening. I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Isabelle and talk about the exhibition, her work, and her personal connection to Nelson Mandela’s struggle.

Making Mandela: Struggle for Freedom

How a trip to South Africa changed one Canadian’s life.

By Matthew McRae

Published: May 10, 2018

Tags:

Photo: CMHR, Aaron Cohen

Story text

Why is this exhibition personally important to you?

I travelled to South Africa in 1994, the year the country held its first democratic elections. That experience completely transformed my life. I was a young woman that enjoyed literature and cinema – I had an artistic side that I thought would be the focus of my life, but actually living that experience made me realize that I was really fascinated by politics. After living in South Africa for nearly a year, I came back to Canada and decided to take up studies in politics.

What are some of the human rights connections to Mandela’s story?

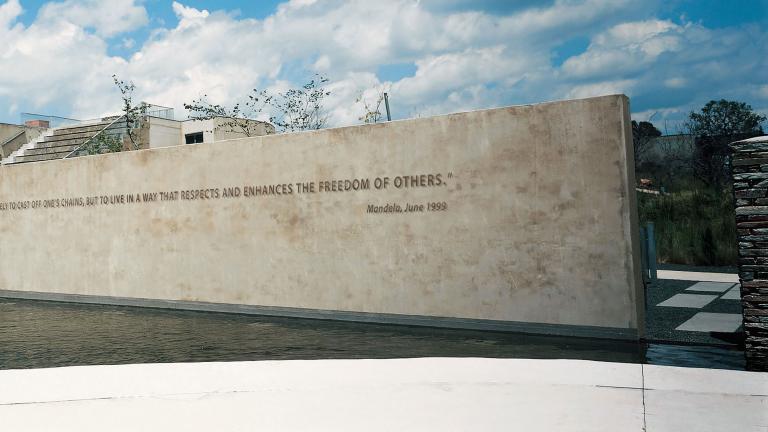

If we want to think about human rights and connections to Mandela, it’s important to explain apartheid. Apartheid was a system that extended and further entrenched racial oppression and segregation in South Africa. It’s really about the fact that most South Africans had their freedoms and rights denied for so long, They were dispossessed of their homes, their land. So, we start the story by helping people understand just how unjust and unequal South Africa was when Mandela was growing up and becoming politicized. Then we introduce Mandela – our main character – who stood up and defied those unjust laws. The story that unfolds from there is his story, but also the broader story of the struggle for freedom in South Africa.

The entrance to Robben Island Prison, where Nelson Mandela served 18 of the 27 years he spent in prison.

Photo: CMHR, Kathleen WiensWhat have you enjoyed most about working on this exhibition?

Well, it’s wonderful to have the chance to work on subject matter that has always been close to my heart. It’s also great to work with so many talented people. It’s never one person who creates an exhibition – it’s an entire team, and so that process of working with the team here, of working with curators in South Africa, has just been an amazing, creative experience that I’ve really enjoyed. I’ve also enjoyed the fact that it’s a bigger show, because that gives us the chance to explore more.

You mentioned working with some curators in South Africa. You also traveled to South Africa to conduct research and secure artifacts for the exhibition. Could you tell me a little about what that was like and how it influenced the exhibition?

It was wonderful to go back to South Africa. Colleagues and I had the chance to visit the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, with which we have partnered for this exhibition. We also visited the District Six Museum in Cape Town. We conducted research at the Mayibuye Archives, which are the archives of the Robben Island Museum. Seeing how they are telling this story was really enriching. I am convinced that Mandela will be completely different because we visited South Africa, did this research and met with South Africans.

A lot of this information is not readily accessible online. It’s detective work, in a way. You have to be there, making the connections, understanding the history and meeting the people. I also think it was important for South Africans to understand why we wanted to share their story, to understand that we wouldn’t just be taking things – requesting loans of artifacts that are crucial to their own history – without consideration for how they see their own history and their own experience.

The Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, South Africa. The Apartheid Museum is a partner for the Mandela: Struggle for Freedom exhibition.

Photo: Courtesy of the Apartheid Museum.What’s the most unexpected thing you learned while working on this exhibition?

I think the most unexpected story was discovering the ways in which Canadians were involved in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. I’ll give you an example: at the time of apartheid, there was an organization called the International Defence and Aid Fund. It had been banned in South Africa, but it continued to operate from London and had a chapter in Canada. As part of its activities, it paid for the legal defense of political prisoners, but it also had another secret component.

This secret program relied on regular citizens who would get the name of someone in South Africa, along with an address. They would start a correspondence with this person in South Africa. The person they were corresponding with would actually be a family member of a political prisoner. They always had to start the correspondence with a very non‐political conversation, because the organization and its activities had been made illegal by the South African apartheid government. The goal was to send funds in this way. They would send money to the families of political prisoners so that the children could continue to go to school, and so that the families would be taken care of to some extent. I actually spoke to Canadians who participated in that. I expected people to be going to rallies and being active on their university campus, but that was another part of the story I really enjoyed discovering.

Why is Mandela’s story relevant to Canadians today?

Mandela played a role in national reconciliation, and I think that for Canadians, there’s something quite worthwhile in exploring that. This exhibition will have resonance with Canadians’ own history: their experience with colonialism, their experience with human rights abuses, and their ongoing experience with reconciliation – which is also still ongoing in South Africa. They’re not the same histories, but very broadly, there are parallels and key points that have resonance and relevance in Canada.

There is also a message in Mandela about becoming involved, about taking a stand to do something about injustices, whether in Canada or internationally. When interviewing people in Canada for this exhibition, I always asked them: “How did you become aware of this situation, and actually decide to become involved in some way?” It could have stayed a distant struggle, but for many Canadians it became relevant in their daily life, as they became involved in this experience of international solidarity, calling for change in South Africa. I think that’s interesting because there are struggles today that people find relevant in the same way.

The exhibition Mandela: Struggle for Freedom will open in June 2018 in the Museum’s Level 1 Gallery.

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Matthew McRae. “Making Mandela: Struggle for Freedom.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published May 10, 2018. https://humanrights.ca/story/making-mandela-struggle-freedom