In 1916, Frederick Lea Hardy, a 17‐year‐old from Brandon, Manitoba, was court‐martialed and sentenced to 18 months of hard prison labour for being gay. Eight months later, in April 1917, when the Canadian Forces needed more troops on the frontlines of the First World War, he was released. He died at Vimy Ridge, where his name was engraved in a monument commemorating those lost. A century later, in his hometown, a battle raged about whether books that address gender identity or sexual orientation should be banned. Put simply, there are those who believe a teenager is old enough to fight and die for their country, but too young to learn about sexuality.

Persecution of queer Canadian soldiers in wartime

Modern anti-2SLGBTQI+ hate echoes the myths and prejudices of the past, threatening to erase queer soldiers’ stories again

By Sarah Worthman

Published: November 8, 2024

Tags:

Photo: Imperial War Museum, Q103094

Story text

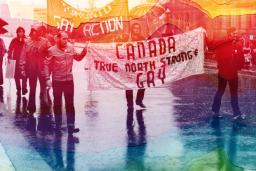

Although there is nothing new about public homophobia, the summer of 2022 saw the beginning of widespread, coordinated protests against the queer[1] community in Canada. Protests began in opposition to all‐ages drag shows in Southern Ontario and spread countrywide. Anti‐queer rhetoric — especially against the trans community and the drag community — has shaped political campaigns from British Columbia to New Brunswick. There has also been an increase in threats and physical violence directed at the 2SLGBTQI+ community and allies, including several bomb threats at schools and libraries, simply because they offered 2SLGBTQI+ programming. The hatred motivating these threats and crimes has a long history in Canada.

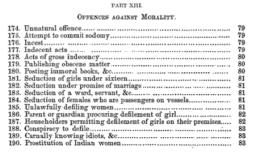

The cultural history of queer criminalization

When European settlers arrived on the shores of Turtle Island, they brought along homophobic cultural and legal traditions that treated queer people as sexual criminals. New France and the English colonies imposed distinct legal traditions and the colonies developed a patchwork of their own criminal laws. All, however, imposed a binary, heteronormative, Christian perspective on sex and gender. By the early twentieth century, Canada’s laws regulating queer sexual behaviour appeared in the Criminal Code under “offenses against morality.” This placed consenting adult queer relationships alongside crimes such as incest, bestiality and some forms of sexual assault and pedophilia[2]. Thus, 2SLGBTQI+ people became associated in law and in popular culture with heinous moral and criminal violations. These biases were still apparent in the early 2000s, when opponents of same‐sex marriage claimed that marriage equality would lead to legalized inter‐species marriage and encourage pedophilia.

This fearmongering, of course, proved false. In Canada, marriage remains a contract between two consenting adults and statistically, according to the National Institutes of Health as well as other US and Canadian studies, the majority of perpetrators of sexual assaults and abuse, broadly considered, are cisgender married heterosexual men.

PART XIII

Offences Against Morality

- Unnatural offence 79

- Attempt to commit sodomy 79

- Incest 79

- Indecent acts 49

- Acts of gross indecency 80

- Publishing obscene matter 80

- Posting immoral books, &c 80

- Seduction of girls under sixteen 81

- Seduction under promise of marriage 81

- Seduction of a ward, servant, &c 81

- Seduction of females who are passengers on vessels, 81

- Unlawfully defiling women 81

- Parent or guardian procuring defilement of girl 82

- Householders permitting defilement of girls on their premises 82

- Conspiracy to defile 83

- Carnally knowing idiots, etc 83

- Prostitution of Indian women 83

From the late 1800s through the 1980s, “gross indecency” legislation played an important role in criminalizing queerness in Canada. Gross indecency was a vague offence that was used to target men at first, but eventually anyone who dared to defy traditional Christian gender norms and relationship conventions. It did not have a formal legal definition, so it could be used arbitrarily to prosecute people for a wide range of behaviour. Men were arrested for anything from holding hands to kissing in public. From the 1940s to the 1970s, people who were convicted of this vague offence could be declared “dangerous sex offenders” and imprisoned for life[3]. Although these punishments were rarely enforced to the fullest extent, laws against gross indecency remained in force until 1987.

Wartime persecution

The Canadian government didn’t just pass laws to criminalize queer people and non‐heterosexual behaviour. They actively sought out and repressed 2SLGBTQI+ Canadians. The military and the public service have a long history of homophobic and transphobic practice. Canada’s persecution of queer public servants from the 1950s through the 1990s (now known as the “Purge”) is becoming better known. But queer soldiers were also arrested, imprisoned and abused throughout every war in the twentieth century, and this is often overlooked.

During the First World War, 19 queer men serving in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) were arrested under gross indecency laws. Their stories reveal the homophobic use of law to repress the 2SLGBTQI+ community. In the court transcripts, witnesses often describe the defendants as “filthy.” As per military policy, the result of each court martial was read out in front of the defendant’s battalion. Queer men would thus be publicly outed to their peers as a form of humiliation. This perpetuated the culture of shame around queerness and also exposed them to homophobic violence from their fellow soldiers.

Many queer people were forced to live secret and fearful lives because of pervasive homophobic surveillance and the risk of betrayal. One example of how those suspected of queerness were treated with contempt and cruelty was revealed in the court trial of Reginald Fuller. Reginald was set up by a former sexual partner, who lured him into an intimate situation and then arranged for several witnesses to be around so he could be arrested.

Frederick Lea Hardy

This history of persecution also involves the only known queer man on the Canadian National Vimy Memorial. Frederick Lea Hardy was raised in Brandon, Manitoba. In 1915, he enlisted to serve in the CEF. He was arrested while stationed with the 8th Battalion near Abele in Belgium for “gross indecency with another male person.” Frederick was immediately detained and tried the very next morning in a court martial. Despite being only 17 at the time, Frederick was sentenced to 18 months imprisonment with hard labour and served roughly eight months in the notorious Winchester prison in England. He was subjected to forced silence, isolation, grueling manual labour and inadequate food.

But by April 1917, the CEF was in dire need of reinforcements. Their desperation for troops outweighed their homophobia. Fredrick’s sentence was suspended and he was released and sent into battle. Given the choice of facing the risks of battle or continued imprisonment, Frederick returned to the frontlines to fight at the Hill 70 offensive in France. On August 15, 1917, Frederick was killed in action. Because his body was never recovered, his name was carved in commemoration on the Vimy Memorial. Frederick Hardy lost his life fighting for a country that had cruelly imprisoned him simply because of his sexual orientation.

For more than 100 years, the story of Frederick was hidden away, along with the history of 18 other Canadian men arrested during the First World War for the crime of being queer (PDF).

There is a lot left to do to raise awareness of their treatment by the Canadian government. But the recent upsurge of anti‐inclusive‐education protests puts our ability to share this history in jeopardy. In 2023, residents of Brandon, Manitoba called on the school board to ban books that contained references to the 2SLGBTQI+ community. The School Board recognized this was a violation of the right to education and the motion was defeated in a six‐to‐one vote. If this group had succeeded, it would have meant that students in Frederick’s own home community wouldn’t be allowed to read about his life.

Look but don’t touch: The limits of queer entertainment

Drag performances — often called “female impersonation” at the time — were a crucial component of the Canadian military in the early twentieth century. By the end of the First World War, almost all CEF divisions had their own concert and performance troupes, most of which would have included “female impersonators.”[4] Drag shows were held to entertain the troops and improve morale. While not all the performers were queer, many were. Performing in drag was one of the only ways to receive attention from members of the same sex in public. Many performers indulged this by playing up their queerness during shows. For example, Canadian drag performer Kitty O’Hara kissed her commanding sergeant in front of an entire audience during a performance in North Macedonia. Unlike Frederick, Kitty was not arrested — because she was performing.

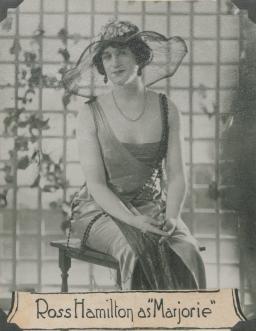

But once the makeup and dresses came off, queer men found themselves at risk of losing their jobs or even being arrested. Ross Douglas Hamilton from Pugwash, Nova Scotia, experienced this firsthand. During the First World War, Ross starred in a vaudeville‐style concert troupe called “The Dumbells” as his drag alter‐ego Marjorie. The troupe was incredibly popular, and Ross was paid by the CEF to travel across Europe with them throughout the war, entertaining Canada’s troops. Marjorie was so popular, in fact, that Ross often had to change out of costume to avoid being mobbed after performances.

After the war, Marjorie toured alongside the Dumbells across Europe and North America. They even did a brief stint on Broadway before the original members disbanded in the mid‐1920s. When the Second World War broke out, Ross enlisted again to perform as Marjorie. However, after a show in 1942, he was outed to his superior officers as queer. Shortly thereafter, Ross was forced into early retirement. After his death in 1965, aside from one newspaper article, his legacy was completely covered up by military officials.

Much like during the First World War, various forms of drag performance are deeply embedded in modern popular culture. Ross’s story shows the paradox of drag performance. It was welcomed as entertainment but also rejected and persecuted as an expression of queerness.

Recently, this phenomenon has started to crop up again, in anti‐drag protests. Drag is often seen and celebrated in casual entertainment. But once that art is directly connected to the 2SLGBTQI+ community or seen to challenge binary gender norms, it is suddenly considered inappropriate, overly sexual, even criminal.

“Queering” Canadian history

Why are these early stories of Canada’s queer soldiers and drag performers only coming to light now, a hundred years later? For decades, discriminatory laws, criminal prosecution and legalized repression silenced 2SLGBTQI+ people and prevented their experiences from being shared and recognized. Prior to a landmark court case in 1992, official “Purge” policies saw 2SLGBTQI+ members of the federal public service and armed forces investigated and legally fired for their sexual orientation or gender identity. This practice continued informally well into the 2000s. This was especially so in federal departments responsible for commemoration and military history, such as Veterans Affairs Canada. These policies cast a long shadow over Canada’s 2SLGBTQI+ community and the country’s capacity to recognize its queer history. Until recently, writing and talking about 2SLGBTQI+ stories and experiences was incredibly stigmatized, especially in the context of the military. Silence and erasure are both a symptom and a form of violence that legitimizes persecution.

There have always been queer people and many have chosen to serve in the military as well as the government of Canada. They endured widespread violent homophobic and transphobic repression and dared to be authentically themselves. As we face the current wave of anti‐2SLGBTQI+ hate in Canada, we can look to our past for inspiration and strength. Sharing these stories is a powerful act of resistance to homophobic myths and attempts to erase Canada’s queer history.

Explore further

Dick Patrick: An Indigenous veteran’s fight for inclusion

By Steve McCullough and Jason Permanand

Patrick was awarded the Military Medal for bravery in the Second World War, but back in British Columbia he was refused restaurant service because he was Indigenous. That didn't stop him.

What Is Two‐Spirit? Part One: Origins

By Scott de Groot

Discover the history and meaning of Two‐Spirit. The term speaks to community self‐determination, rejects colonial gender norms and celebrates Indigenous sexual and gender diversity.

Claiming our rights as a transgender family

By Rowan Jetté Knox

Names and pronouns may change but love stays constant.

Love in a Dangerous Time: Teacher Guide

Support your students as they learn about the historical significance of the LGBT Purge and the resilience of 2SLGBTQI+ communities in Canada.

References

- Queer is defined as a term that can include, but is not limited to, gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, Two‐Spirit, intersex and asexual people. Many who study 2SLGBTQI+ history use “queer” in historical analyses because it is a fluid category of identification that encompasses both gender and sexuality. Back to citation 1

- This section addresses “seduction” of girls between 14 and 16 and various kinds of “moral defilement.” Back to citation 2

- Tom Warner. Never Going Back: A History of Queer Activism in Canada. University of Toronto Press, 2002. Back to citation 3

- “Concerts and Theatre,” Canadian War Museum website Back to citation 4

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Sarah Worthman. “Persecution of queer Canadian soldiers in wartime.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published November 8, 2024. https://humanrights.ca/story/persecution-queer-canadian-soldiers-wartime