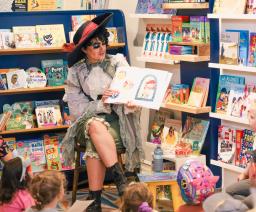

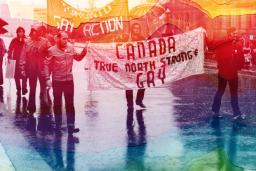

Performing in drag is an old art form that is experiencing a new mainstream popularity. But in recent years, drag has also become a lightning rod for those who oppose 2SLGBTQI+ rights and expression. Drag storytime for children, in particular, has drawn ire from protestors.

She said | He said

Drag performers talk about their experiences in today's climate

By

Leslie Vryenhoek, editor

Published: February 5, 2025

Tags:

Photo: CMHR, Douglas Little

Story text

We asked two performers – a drag queen and a drag king – to weigh in on their experiences, why they think drag matters, and how the current climate has affected them:

- Cyril Cinder has been performing as a drag king for ten years. He is based in Ottawa.

- Kymera crested two years as a drag queen in 2024. She’s based in Winnipeg.

On why they perform drag

Kymera: Like many people, I was introduced to drag as an art form[1] by Ru Paul’s Drag Race, but I’m also a fashion designer, and there were a few people in the Winnipeg community I constructed outfits for. Then my eventual “drag mom,” Ruby Chopsticks, was putting on a show focused on BIPOC performers and asked if I’d be willing to try drag. I said ok. It’s been a wild two years since.

Being able to experience the totality of myself is really what draws me to drag. I get to be as masculine or feminine or androgynous as I want, and that feeling can change from day to day in how I want to present myself and behave. A big part of it is that I can get in touch with that side of my femininity that, as a young kid, I wasn’t allowed to lean into.

Also, I grew up a big lover of pop music and that’s what I like to perform. Whether you’re performing for a crowd or just five people who are really enjoying what you do, you get that energy amplified and reflected back at you.

It’s a wonderful feeling.

Cyril Cinder: After I saw my first drag show, I went to social media and posted something like, “If I’d been born a man, I would totally be a drag queen!” Thankfully, I had friends who were more enlightened than I was at the time and who said, “Hey, women can be drag queens – but you’ve been dressing up and playing the boy roles in theatre since you were 14, so you might really enjoy being a drag king.”

About two months later I performed on stage for the first time.

It’s been a source of genuine self‐discovery. When I starting as a drag king, I performed predominantly in burlesque spaces because drag spaces haven’t always been the most integrated. I spent time with queer performers and queer women, and I recognized that this was my lived experience. After doing drag for about six months, I realized I wasn’t straight – that I was actually bisexual and non‐binary. Through this artistic medium, it was safe to try on a different identity and see how it felt, and how other people responded to it. For me, it continues to be that safe avenue for self‐expression, for exploration and to create performance art.

I’m also a registered psychotherapist. I specialize in working with the 2SLGBTQIA+ community as well as survivors of childhood trauma, and I find drag is a great outlet to help me process some of what comes up in my work. I can be in this vibrant, diverse, resilient community – it contributes so much to my own resilience and well‐being.

On equity and inclusion in the drag realm

Kymera: There are a lot of BIPOC performers, but there’s still work to be done if we talk about not just equality but equity. The queer community is not a monolith, so not everyone has the same issues or the same viewpoint.

But there is an ongoing conversation, when people are putting together drag shows, around, “What does your cast look like?

Who are the people that you’re booking?

And who are the people in charge who are making those decisions about who gets cast?” And especially in Winnipeg, there’s a focus on specifically how we make things more equitable for Indigenous performers. The easy part of that conversation is, “How many people do you book in a show that identify as BIPOC? How many people do you book that identify as trans?”

The harder part of the conversation is: “Are we doing this in a holistic way or are we doing it to check a box?” Smarter people than me are still attempting to figure out the right way to tackle this, but it is an ongoing conversation where people are trying to figure out how to do it thoughtfully and not just contribute to tokenism. It’s not easy to find a way forward that everyone can agree on.

Cyril Cinder: There is this idea that it’s just not as exciting or dangerous [when a woman dresses as a man]. I think there’s a very misogynistic tone that can exist in that – and genuine gatekeeping. A big part of why drag kings are not as known publicly is because we’ve been kept out of opportunities.

Ru Paul’s Drag Race is the biggest stage for drag performers in the world, and it has helped launch the careers of the most famous drag queens in the world. And drag kings are not allowed on the show – they audition every year and are not cast. So for the casual enjoyer of drag, who maybe follows Ru Paul’s Drag Race and who maybe follows a few drag performers on social media, it’s possible for them to not even know drag kings exist.

Which is too bad because I think we all have something really wonderful to contribute to the conversation about what it means to be human and drag is an art form where we get to explore an entire side of that. That conversation is best advanced when everybody gets to contribute to it and share their lived experiences of it.

On protests, threats and “saving the children”

Cyril Cinder: When I started in 2014, I had this impression that it was only going up from here – that things would just get easier for us.

I was wrong about the slow march of progress. I’ve done many drag storytimes over the years. Back in maybe 2018, we might have one person come and hold up a sign – and they would be swiftly escorted out. It was like ok, those people exist on the fringe. For our first event back after COVID, we planned a drag storytime in partnership with Capital Pride and the National Arts Centre here in Ottawa. Beforehand, people were posting things like, “Everybody needs to come to the NAC to save the children…. They’re grooming our children and we can’t allow this to happen.” It was clear this was a big attempt to mobilize. And they showed up, yelling things and carrying signs that were homophobic and transphobic and full of disinformation.

I’m extremely grateful that community supporters came out who vastly outnumbered the protestors.

Unfortunately, it’s happened several times since. And it’s been really frightening. I’ve gotten numerous death threats and people trying to find my home. I had to talk with the psychotherapy clinic where I work to let them know they might get a phone call about me being “a predator,” and I wanted them to have the context for why it was happening. I’ve had people at these events grab me and try to pull me to them. I’ve seen people punched in the face and thrown on the ground. There’s been heavy police presence. It’s been a bit of a collective trauma to see that wow, these people hate us so much – and on the basis of lies. It’s especially that: they lie so much, and the lies are so overt.

I got a large dog, just to try to feel a little safer at home.

During COVID, I did drag shows in my driveway just to give people a little joy and something positive. When all this rhetoric started up, I realized I can’t do that anymore, someone’s going to show up at my house. It just takes one person who truly believes that by harming me they’re going to save children for that harm to be justified in their minds.

So it’s difficult to see so much of the conversation in these protests be about drag queens but not include some of my lived experience. The people who are showing up to protests – they also don’t know what a drag king is. They leave comments on social media like “You’ll never be a real woman!” – I’m like “Hey, thanks!” – even though I have a moustache on, they don’t get it. But I want my allies to get it. And when [the protestors] do get it, the thing they threaten me with is sexual assault. Threats of “corrective rape” are a thing that I have experienced as a drag king.

I find the “grooming” allegation especially incensing, because I work with people who survived being groomed, and I know what that behaviour really looks like and the harm it does. Grooming is a conditioning that is enacted on a child over time so that when the abuser does cross the line into abuse, they won’t be reported. And it has to have intent. I don’t understand how me dressing up and reading a book about love and self‐acceptance could ever be justifiably compared to that. I want kids to be safer in their communities, actually.

Kymera: I’ve been in shows that have gotten some pushback. Recently, this past New Year’s Day, I was part of a family‐friendly drag show taking place at The Forks [in Winnipeg] and there was a push on social media… People were saying it was not child‐friendly, that we were “predators” trying to take advantage of kids. It gets quite frustrating as a performer, as a drag artist, when you take great care in making sure that everything is appropriate for a specific audience, but it gets wilfully misinterpreted.

All we want to do is share our art with people. Of course some of that art is not child‐friendly, but like every establishment that produces art, we tailor our stage presence and our performances. I liken it to taking a kid to the movie theatre – there are [age] restrictions based on the material that’s being presented. Drag is no different.

There are so many different identities and definitions of gender out there. I think for some people, that can be scary, to have something that doesn’t exactly reflect what you were taught growing up. To try to synthesize your world knowledge with something that comes from outside and challenges your world can be a source of great conflict for people, and I think that’s what we’re seeing.

On the relationship between drag bans and transphobia

Kymera: Bans around drag are really, at their core, focused on trans individuals. When you look at the legal definitions of drag and the legal definition of what a trans person is in a lot of states in the US and some places here, there’s quite a bit of overlap. We may look the same to some, but these are separate and distinct things. Even though drag is a performance of gender and trans people are not performing for an audience – it’s who they know themselves to be – things get muddier legally. So drag bans can have quite a large effect on the trans community.

Cyril: A lot of people [who are protesting drag] really don’t understand the difference. They don’t get it and they don’t seek to – they’re not interested. But we can’t discuss the safety of drag as an art form without also including a conversation about trans people who are just trying to live their lives. Attacking us is the proxy attack.

And while I experience a lot of threat, I also get to take my drag off after a performance and walk around out of that costume – because it is a costume, a performance. I’m still quite visibly queer – I’m married to a woman and style myself in pretty queer ways – but I don’t get clocked in public as a trans person. So there’s a certain amount of privilege that comes from that.

On the value of drag storytime

Kymera: For kids, drag storytime is often the first time they might see or interact with someone who is queer. Growing up, I didn’t have a lot of people in my community who were queer, so it was really isolating. I think my experience might have been a lot easier had I known I wasn’t alone, that there were other people out there like me.

Especially growing up in the nineties after the peak of the AIDS crisis, there was a lot of doom and gloom… If you were queer, there was harm and disease that was going to come for you. Having queer people around who are happy and can live long lives and build relationships and build community – that would have been very comforting and healing for me as a kid.

Cyril: Storytime is important because it’s an anti‐bullying, pro‐literacy initiative. It’s an opportunity for kids to see somebody sparkly and interesting showing a strong enthusiasm for reading, and also to validate that people whose gender presentation is a little different than you might be used to, they can be cool too. It’s all good.

And it’s also an opportunity for queer families to gather, because queer people have kids, and they deserve a safe, all‐ages space to come together.

On why the world needs drag

Kymera: I think most people, to varying degrees, have some level of masculinity or femininity in them, and I think most people in a heteronormative culture are pushed into only identifying with the gender they were assigned at birth. For a lot of drag performers, the exploration of gender is something that has always been inside of them and drag is a safe avenue to explore gender.

I also want to say that queer people are not here to take anything from you – they’re not here to harm you. We’re all just trying to live our lives as authentically as every person.

Cyril: As drag performers, our job is to be the biggest representation of the community. We are here to be loud and sparkly and just the gayest thing in the room. We’re saying, “Don’t worry honey, nobody’s looking at you – I’ve got three‐inch eyelashes and a wig and all of these rhinestones to focus on. So you do you.” We make it a little safer for everyone else to be their authentic selves.

As much as I think there are many important conversations we’re having about defending drag and about criticisms of misogyny and exclusionary practices within the drag community, drag is fundamentally something that is wonderful, that is beautiful and that is so, so resilient as an art form. Even if you are just putting on a wig and some heels and lip syncing to Britney Spears in a dingy bar, you are still doing something radical and powerful and worth celebrating. It’s a carrying forward of the spirit that the queer community has had to embody throughout human history just to be able to exist.

It’s that statement that we’re here, we’re queer, and no society has or ever will exist without us.

Ask yourself

What are ways that you express your own uniqueness?

Have you ever been threatened because of how you look or act?

How does a fear of people who are different fuel discrimination?

Dive Deeper

An interview with Tegan and Sara

By CMHR Curatorial Team

Tegan and Sara, identical twin sisters hailing from Calgary, Alberta, have been performing together for more than 25 years. The sisters have openly identified as queer and as such, their music has motivated, encouraged and inspired a generation of LGBTQ+ and feminist fans at home and abroad.

Persecution of queer Canadian soldiers in wartime

By Sarah Worthman

Modern anti‐2SLGBTQI+ hate echoes the myths and prejudices of the past, threatening to erase queer soldiers’ stories again.

The Re‐emergence of 2Spirit People in the 21st Century

By Albert McLeod

Two‐Spirit individuals were cherished in Indigenous cultures, Albert McLeod writes, but European colonizers imposed rigid, binary definitions of gender and sexuality that activists are working to dismantle.

Love in a Dangerous Time: Teacher Guide

Support your students as they learn about the historical significance of the LGBT Purge and the resilience of 2SLGBTQI+ communities in Canada.

References

- In Western cultures, cisgender men have dressed as women to perform on stage since ancient times. There is also a centuries‐old tradition of cisgender women dressing as men, including in vaudeville acts, though the term “drag king” is a newer development. Other cultures have similar performing traditions. However, it should be noted that performers of any gender can be drag queens or kings. Back to citation 1

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Leslie Vryenhoek, editor. “She said | He said.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published February 5, 2025. https://humanrights.ca/story/she-said-he-said