Canada takes pride in the history of the Underground Railroad. We celebrate being a destination for freedom‐seeking enslaved Americans fleeing to the north. But Canada also has its own long history of slavery, and the legacy of slavery lives on in anti‐Black racism in Canada today.

The story of Black slavery in Canadian history

Slavery was part of Canada’s colonial nation-building for over 200 years

By Steve McCullough and Matthew McRae

Published: August 22, 2018 Updated: February 16, 2023

Tags:

Photo: Aaron Cohen, artifact from Amherstburg Freedom Museum

Story text

Practices of enslavement in what is now Canada predate the arrival of Europeans. Some Indigenous peoples enslaved prisoners taken in war.1 Europeans brought a different kind of slavery to North America, however.

Many Europeans saw enslaved people merely as property to be bought and sold.2 This “chattel slavery” was a dehumanizing and violent system of abuse and subjugation. Importantly, Europeans viewed slavery in racist terms. Indigenous and African peoples were seen as less than human. This white supremacy justified the violence of slavery for hundreds of years.

The slave trade inflicted unimaginable suffering on millions of people. It also created racist stereotypes and biases that live on in Canadian society even now, almost 200 years after the abolition of slavery.

What was the transatlantic slave trade?

In the 15th century, European colonial powers began the large‐scale practice of transporting enslaved people from Africa. Slave traders shipped them under horrifying conditions across the Atlantic. Colonial authorities and landowners forced them to serve as slave labour in the Caribbean and in North and South America.

A pattern emerged called "triangular trade." European merchants brought trade goods from Europe to Africa. In Africa, they exchanged their goods for enslaved people. In the Americas, the surviving enslaved people were sold, and goods produced by slave labour were carried back to Europe for sale.

More than 12 million African people were taken into slavery. At least two million more died en route across the Atlantic. The widespread violence of slave raids and kidnappings killed and displaced millions more.

European colonizers held a racist double standard about slavery. Slavery had been illegal in France and England for hundreds of years. And yet both England and France freely enslaved millions of Black people in their faraway colonies. The transatlantic slave trade was thus a distinctively colonial and white supremacist form of violence and exploitation. It was a key aspect of European imperialism and exploitation across half the world.

Slavery in New France

The colony of New France was founded in the early 1600s. It was the first major European colonial settlement in what is now Canada. Slavery was a common practice in the territory. When New France was conquered by the British in 1758–1760, records revealed that approximately 3,600 enslaved people had lived there since its beginnings.3 The majority of them were Indigenous (often called “Panis”4). Black enslaved people were also present because of the transatlantic slave trade.

King Louis XIV authorized the importing of enslaved Black people to New France in 1689, at the request of the colonial government. In 1709, New France passed laws that explicitly legalized slavery and defined slaves as property – and thus as having no rights.

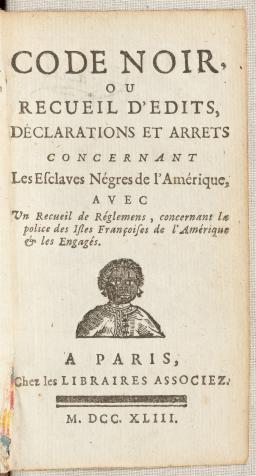

A set of regulations called the Code Noir governed slavery in most French colonies. It’s unclear if the Code Noir formally applied in New France, but it strongly influenced the customs and practice of slavery there.5

Colonial slave laws such as the Code Noir provided a few minimal protections to enslaved people. The Code required owners to provide slaves with food, shelter, and clothing. But it also empowered slave owners to inflict violent punishments on slaves, including branding, mutilating and even killing them.

Free Black people in New France were at constant risk of being enslaved. In 1732, Governor Jonquierre enslaved a Black freedom seeker who had arrived from New England on the basis that “a black is a slave, wherever he may be found.”6

The runaway slave…shall have his ears cut off, and shall be branded with the fleur de lis on the shoulder…. On the third offence, he shall suffer death.

Slavery in British North America

Slavery continued after the British formally took control of New France in 1763. The formal agreements that ended the war affirmed the continued enslavement of Black and Indigenous people.

The era of British rule saw an increase in the number of Black enslaved people in Canada. In the late 1770s and early 1780s, Loyalists fleeing from the newly independent United States brought hundreds of enslaved Black people with them. John Simcoe, the first governor of Upper Canada (now Ontario), was surprised at how many colonists owned slaves when he arrived in 1792.7

Early Canada is sometimes described as a “society with slaves” rather than a “slave society." At the time, much of the Caribbean and the southern United States were slave societies. There, large‐scale slave labour on plantations was a dominant force in economics, politics and culture.8

Enslaved people made up a smaller proportion of the population in early Canada than in plantation economies. This meant they toiled in relative isolation, which inhibited the creation of shared community. It possibly enabled even more intense surveillance by white society.9

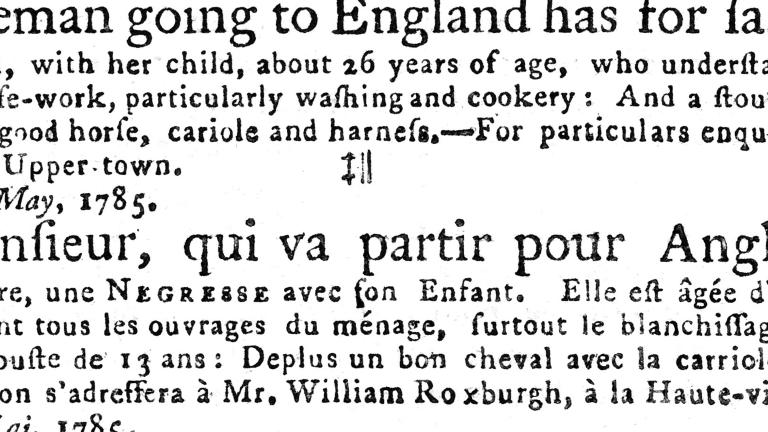

White colonists of many walks of life owned slaves. Merchants owned the largest number, but farmers, the political elite, and the Church were also slave owners. Enslaved people acted as servants, as farm labour and as skilled artisans. Their forced labour contributed to the success and prosperity of the British colonies that became modern Canada.

The nature of slavery meant that its victims were stripped of their basic human rights, exploited for labour, and subjected to arbitrary violence and suffering. Most wills from the time treated enslaved people as nothing more than property, passing on ownership of human beings exactly as they would furniture, cattle or land.10

Slave owners subjected enslaved people to terrible working and living conditions. Physical and sexual abuse was a constant threat. Enslaved people lived tremendously difficult, very short lives. Enslaved Black people in New France, for instance, died at an average age of only 25.11

This is what needs to be acknowledged in Canada…. We’re talking about, within these Canadian colonies, enslaved Africans…who had all kinds of violence committed upon their bodies.

Resistance, escape and activism

Enslaved people often resisted the institution of slavery. They fought back in many ways: by asserting their humanity in the face of a system that wished to deny it to them, by running away from slave holders or by assisting other freedom seekers. In fact, in 1777, a number of enslaved people fled from British North America into the state of Vermont, which had abolished slavery in that same year.12

Public campaigns against slavery took hold in England in the late 1700s. Formerly enslaved Black authors and activists, such as Ignatius Sancho and Olaudah Equiano, were influential in the abolitionist fight. From the 1770s on, popular memoirs of slavery and widely publicized court cases that freed enslaved people inspired a growing resistance to slavery in England.

Abolitionist sentiments took longer to reach Canada. But by the turn of the 1800s, attitudes to slavery among the free population of British North America were beginning to change. Accounts of dehumanizing violence and moral arguments against slavery began appearing in newspapers.

Despite the influx of enslaved people in the early 1780s, few people remained enslaved in Canada by the late 1790s.13 Slavery remained legal, however, and pro‐slavery merchants and politicians attempted to keep it that way.

The abolition of slavery in British North America

In 1793, a Black man named Peter Martin petitioned Governor Simcoe to act against a slave owner who had violently transported an enslaved Black woman, Chloe Cooley, from Upper Canada to the United States to be sold. This slave owner’s actions were entirely legal at the time, and this case seems to have inspired Simcoe to introduce the first anti‐slavery law in British North America.

Upper Canada passed an Act in 1793 intended to gradually end the practice of slavery. The law made it illegal to bring enslaved people into Upper Canada and declared that children born to enslaved people would be freed once they reached 25 years of age. It did not free any enslaved people directly, but any enslaved person who arrived in Upper Canada would be considered free.14

A similar act failed to pass in Lower Canada (now Quebec) thanks to pressure from influential slave owners – including elected representatives – who blocked it. But even in the absence of outright prohibition, the legal status of slavery was weakening. Throughout the early 1800s, courts in various colonial jurisdictions (notably Lower Canada and Nova Scotia) ruled against slave owners and freed formerly enslaved people.15

On March 25, 1807, the slave trade was abolished throughout the British Empire, including British North America. This made it illegal to buy or sell human beings and so ended British participation in the transatlantic slave trade. But it didn’t outlaw holding and exploiting enslaved people. The overall practice of slavery was abolished everywhere in the British Empire in 1834. Notably, Prince Edward Island had already pronounced the complete abolition of slavery in 1825.16

How can slaves be happy when they have the halter round their neck and the whip upon their back? And are disgraced and thought no more of than beasts?

After the slave trade

The abolition of slavery allowed the British colonies in North America to become a destination for escaped enslaved people in the United States who made their way North via the famous Underground Railroad. This was an informal network of people, organizations, hiding places, homes, routes, transportation networks and tactics that supported freedom seekers in their clandestine escape from slavery.

However, Black people in Canada still faced considerable racism in the colonies (later, a country) that had practiced slavery for over 200 years. Racist attitudes and practices sharply limited Black people’s opportunities.

Segregated education was legally enforced in Upper Canada in the 1850s.17 Informal segregation still marginalized Black people a hundred years later, when Viola Desmond faced anti‐Black racism in education and at the theatre. Many other Black Canadians resisted the practice of segregation in the first half of the 20th century.

Until the Second World War, the vast majority of working Black women were restricted to being domestic servants.18 Some trade unions were explicitly anti‐Black through the 1950s. Sleeping car porters were the first Black workers to organize their own union to fight for better pay and working conditions.

Formal protection from racist education, employment, and housing restrictions only began to appear in the 1950s and 1960s. Various provinces passed laws imposing fair employment practices and created bills of rights and the first human rights commissions.19 But as the Black Lives Matter movement shows, the struggle against anti‐Black racism continues in 21st century Canada.20

Slavery was legal and practiced in early Canada for longer than it has been abolished. And many racist ideas, stereotypes, and practices that live on today have their roots in the dehumanization of Black people that justified and sustained the slave trade.21

Though formalized Black bondage was officially over, the meaning of Blackness had been consolidated under slavery.

This story was written using research conducted by Mallory Richard, a former researcher and project coordinator at the CMHR.

Ask Yourself

How do people talk about race and ethnicity in my community?

When and where did I learn about slavery?

How well known is the history of slavery in Canada?

Indentured servitude and slavery

For many years, the practice of indentured servitude existed alongside slavery in what is now Canada. Under the system of indentured servitude, individuals signed a contract committing perform unpaid labour for a set number of years in exchange for transport, shelter and food.

Indentured servitude was cruel and exploitative but very different to slavery. At the end of their contracts, indentured servants were free to go, and sometimes received a payment of land and goods. In contrast, slavery defined humans as property and involved lifelong forced labour. The children of enslaved people also became property, making slavery intergenerational.

Explore Black Canadian history

Black History and human rights

Discover Black stories, voices, struggles and triumphs. Learn about personal and collective acts of resistance and the ongoing fight for equality.

References

- Charles G. Roland, "Slavery" in the Oxford Companion to Canadian History, 585.

- James A. Rawley. The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History, revised edition. Dexter, MI: Thomson‐Shore Inc., 2005: 7.

- Robin Winks. The Blacks in Canada: A History, second edition. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997: 9.

- Refers to "Pawnee," an Indigenous nation which inhabited the basin of the Missouri River. “Slavery.” Virtual Museum of New France. Canadian Museum of History. https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/population/sl… 22 August 2018.

- Marcel Trudel. Canada’s Forgotten Slaves: Two Hundred Years of Bondage. Trans. George Tombs. Montreal: Vehicule Press, 2013: 119–122.

- Trudel, 57.

- Afua Cooper. "Acts of Resistance: Black men and women engage slavery in Upper Canada, 1793–1803." Ontario History 94.1 (Spring 2007): 5–17.

- Harvey Amani Whitfield. North to Bondage: Loyalist Slavery in the Maritimes. Vancouver: UBS Press, 2016, 49.

- Robyn Maynard. Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present. Halifax and Winnipeg: Fernwood, 2017, 23.

- Winks, 53.

- Trudel, 136.

- Ken Alexander and Avis Glaze. Towards Freedom: The African‐Canadian Experience. Toronto: Umbrella Press, 1996: 29.

- Trudel, 250ff.

- "Significant events in Black Canadian history." Black History Month. Canadian Heritage. https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/campaigns/black-history-mont…. Accessed 22 August 2018.

- Winks, 99; Trudel, 240ff.

- Harvey Amani Whitfield and Barry Cahill. "Slave Life and Slave Law in Colonial Prince Edward Island, 1769–1825." Acadiensis 38 (2009). PEI was also unique in the British colonies in having explicitly made slavery legal in 1781. In the rest of British North America, slavery was upheld by treaties, common law and social acceptance rather than legislated slave codes.

- Kristin McLaren, "'We had no desire to be set apart': Forced segregation of Black students in Canada West public schools and myths of British egalitarianism." The History of Immigration and Racism in Canada: Essential Readings. Barrington Walker, ed. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 2008.

- Dionne Brand, "'We weren’t allowed to go into factory work until Hitler started the war’: The 1920s to the 1940s." The History of Immigration and Racism in Canada: Essential Readings. Barrington Walker, ed. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 2008.

- Winks, 428ff.

- Rodney Diverlus, Sandy Hudson, and Syrus Marcus Ware, eds. Until we are free: Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada. Regina, U Regina Press, 2020.

- Maynard, passim.

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Steve McCullough and Matthew McRae. “The story of Black slavery in Canadian history.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published August 22, 2018. Updated: February 16, 2023. https://humanrights.ca/story/story-black-slavery-canadian-history