Dick Patrick was awarded the Military Medal for bravery in the Second World War, but back home in British Columbia he was refused restaurant service because he was Indigenous. He became a local legend for repeatedly demanding to be served and then getting arrested, in a year‐long act of civil disobedience that saw him thrown in jail 11 times.

Dick Patrick: An Indigenous veteran’s fight for inclusion

By Steve McCullough and Jason Permanand

Published: January 13, 2020 Updated: October 31, 2023

Tags:

Photo: Robert Ciavarro, CC BY-NC-ND 2.01

Story text

Dominic "Dick" Patrick was born in 1920 in Saik’uz First Nation (also known as Stoney Creek), a Dakelh (Carrier) community located near the geographical centre of British Columbia. He enlisted in the Canadian army in early 1942 and fought in Europe until the end of the war. Patrick died in 1980 and is remembered by his family and community as a brave soldier and a local champion who stood up for Indigenous rights.

Heroism and commendation

On October 23, 1945, Patrick found himself at Buckingham Palace, face to face with King George VI, who awarded him the Military Medal for gallant and distinguished conduct.

Patrick earned his Military Medal thanks to a feat of bravery that helped Canadian forces dislodge key German defences as the Allies advanced east into Belgium after the Normandy landings. In the village of Moerbrugge, just south of Brugge, Patrick and his crew helped to secure and hold an important river crossing. For two days they endured heavy artillery fire and were starting to run dangerously low on supplies. The Allied troops eventually advanced across a temporary bridge, but fog and incoming fire made the German positions hard to determine. Patrick offered to go ahead on foot to find out where the enemy was.

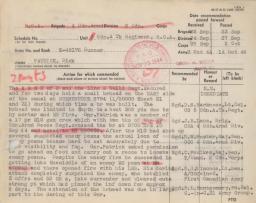

The commendation for his medal describes what happened next: “Despite the enemy fire, he succeeded in getting into the middle of an enemy machine gun position and there opened fire with his light machine gun. His daring attack completely surprised the enemy, who totalled three officers and 52 other ranks, into surrender and cleared out a strong point which had pinned the infantry down for approximately two days. The extension of the bridgehead was due in large part to the daring of this gunner.”

It is worth repeating: Dick Patrick ventured behind enemy lines under very difficult conditions and captured more than 50 soldiers and officers, single‐handedly.

The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada and the Lincoln and Welland Regiment secured and for two days held a small bridgehead on the east side of the canal at Moerbrugge during which time a bridge was built. The bridgehead was limited in depth to about 300 yards due to heavy mortar and machine gun fire. Gunner Patrick was a member of a 17‐pounder M‑10 machine gun crew which with two tanks of the 29th Canadian Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment crossed the bridge at 0700 hours, 10 September 1944. After the M‑10 had shot several suspected enemy positions, the actual location of the enemy positions became hard to estimate accurately due to poor visibility and fog. Gunner Patrick asked permission to go ahead on foot and carry out reconnaissance to locate enemy positions. Despite the enemy fire he succeeded in getting into the middle of an enemy machine gun position and there opened fire with his light machine gun. His daring attack completely surprised the enemy, who totalled three officers and 52 other ranks into surrender and cleared out a strong point which had pinned the infantry down for approximately two days. The extension of the bridgehead was due in large part to the daring of this gunner.

When he was being honoured for this feat at Buckingham Palace, Patrick had the ear of King George VI and did not waste the opportunity. He spoke at length about the discrimination First Nations people faced back in Canada.

I told [King George VI] when my people went into Vanderhoof, they were not allowed to go into restaurants, use public toilets, and had to come in the back door of a grocery store to buy groceries. We spoke for a long time about the injustice to my people. He told me he would endeavour to help my people.

Patrick was perhaps inspired to speak out like this because he had been exposed early in life to the colonial institutions, genocidal policies and racist attitudes that demeaned and restricted his people.

Childhood and residential school

Patrick was the oldest child in his family, so he was the first to be sent to nearby Lejac Indian Residential School. Like many residential schools, it was a place where many students suffered from physical, sexual and psychological abuse.

Lejac school made headlines not long after Patrick left, when four young boys ran away from the facility on New Year’s Day 1937, only to be found dead from the cold. The boys had made it almost all the way back to their home community some 11 kilometres away. The British Columbia government’s report into the deaths took the school to task for failing to organize a search party, having poor relationships with students’ families, and practicing “excessive corporal punishment.”2, 3

Patrick is remembered by his family as a sporty, outdoorsy and fun child. “He was always happy and laughing and loved to tell jokes,” his sister Arlene John said in a 2019 interview. “He loved sports too – especially the rodeo, which he rode in later on.”

In his youth, he helped take care of cattle and horses on the family farm, and after he left Lejac he continued to work on the farm and in the bush, where he trapped and occasionally worked in mining and forestry.

Military life

At the age of 22, Patrick volunteered to serve in the Second World War. He was one of at least 3,000 First Nations members—including 72 women—who enlisted for duty in the Canadian Armed Forces. Patrick was one of 15 Saik'uz soldiers who volunteered for service, according to the First Nation.

For much of his time in Europe, Patrick served with the 5th Canadian Anti‐Tank Regiment in the 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division. His rank was Gunner and he was a crew member on an M10 self‐propelled anti‐tank gun.

The camaraderie of military life meant that Indigenous personnel generally experienced respect and acceptance while serving in the forces. Arlene John said, "My brother was treated with respect when he was overseas and could do what all the other soldiers did.” Historian Scott Sheffield notes that military service offered many Indigenous people a "powerful egalitarian experience" and that unlike many of their experiences with racism in civilian life, they were by and large “respected and honoured for their character and capacity."4

John recalls that, according to her brother, "When he was in the war, they all treated each other with love, respect and kindness, the same as everyone else, and they loved each other."

The return home

This experience of respect and acceptance must have been a striking contrast to the racism Patrick was familiar with from his upbringing, the discrimination that motivated his conversation with King George VI, and the prejudice that was waiting for him on his return home.

Six months after the King awarded him the Military Medal, Patrick was back in British Columbia, facing a judge who sentenced him to prison for daring to demand fair and equal treatment.

In Vanderhoof, the closest town to Patrick’s home community, many businesses refused to serve First Nations people. Those restaurants and stores that would accept Indigenous customers typically segregated them in back rooms or forced them to use separate entrances. Arlene John recalls that her parents “used to drive a sleigh in the winter to get groceries, tie up their horses in the back, and they had to go in the back door.”

Patrick was discharged from duty in March of 1946. On his first visit to Vanderhoof, Patrick walked into the Silver Grill Café, a restaurant that was widely known to refuse to serve Indigenous people. He sat down and ordered a meal. When he was denied service, he refused to leave. The proprietor called the police, who arrested Patrick and charged him with disturbing the peace. He was sentenced to six months in Oakalla Prison, which was infamous for its brutality and terrible living conditions.

From prison he called someone he hoped could help: activist Maisie Hurley, who advocated for First Nations people and founded the country’s first and only First Nations newspaper at the time, The Native Voice. With her help, Patrick was shortly released.

But Patrick wasn’t done. Released from prison, he was sent back the nearly 900 kilometers to Vanderhoof by bus. And when he got off the bus after this very long journey, he went straight to the Silver Grill Café, sat down, and ordered a meal. Again, he refused to leave, and again, he was arrested and sent to prison. Over and over, Patrick would insist on being served, be refused and be imprisoned.

His stubborn protest led him to be thrown in Oakalla Prison 11 times over the course of about a year. Each time Patrick landed in jail, he would call Hurley and she would once again advocate for his release.

In one year I spent 11 months in prison. I would just get off the bus and walk into a restaurant and they would send me back…. I was bound and determined to show them they could not treat my people like animals.

Dick Patrick remembered

Patrick didn’t get his meal at the Silver Grill Café, but his actions spoke volumes to the people around him. His brother‐in‐law, Johnny John, recalls that Patrick’s struggle drew attention to the reality and the injustice of discrimination in the local community: “After he had done all that, everybody knew what was going on.” Arlene John also recalls that her brother’s protest “woke everyone around him up to the realities of the world we were living in.”

When he died in 1980, Patrick was buried in his home community of Saik’uz First Nation with full military honours. Although he received a well‐earned medal for his bravery as a soldier overseas, he received scant public recognition for his brave effort to fight for human rights back home in Canada.5

Arlene John recalls, “My mom told us growing up the importance of truth. Dick stood up for truth and the rights of our people. He fought in the war, but he never bragged about it. He wanted everyone to be treated the way he was on the front line.”

John also describes her brother responding to the challenges and adversity he faced with affection and humour. She said in an interview, “He always treated people with respect and would always be laughing and joking even when things were not good.” She fondly remembers how he would joke with his friends and family, saying “Don’t worry, I still love you second‐class citizens.”

Ask Yourself:

Is there anyone in my community who is excluded because of who they are?

How can I promote acceptance and inclusion in my family, school and workplace?

Where can I learn more about people who’ve made a difference in my community?

Explore stories of courage and hope

Claiming our rights as a transgender family

By Rowan Jetté Knox

Names and pronouns may change but love stays constant.

The story of Nelson Mandela

By Matthew McRae

Mandela spent 27 years in prison for opposing South Africa’s apartheid system. He refused to give up his efforts to achieve equality for all people.

The Wilcox County integrated prom

By Matthew McRae

In 2013, graduating students at a high school in Georgia, held their school’s first‐ever integrated prom, where Black and white students could attend together.

References

References

1 "Winter, near Vanderhoof, BC,” Robert Ciavarro, Flickr, Creative Commons Attribution‐NonCommercial‐NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license (CC BY‐NC‐ND 2.0). https://www.flickr.com/photos/bishopsgreen/2479650412/in/album-72157604…

2 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. They came for the children: Canada, Aboriginal peoples, and residential schools. 2012. http://www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/resources_2039_T&R_eng_web[1].pdf

3 Government of British Columbia. Inquisition. Indian Affairs Record Group 10, vol. 6446, file 881–23, part 1.

4 Canada. Parliament. House of Commons. Standing Senate Committee on Veterans Affairs. Indigenous Veterans: From Memories of Injustice to Lasting Recognition. 42nd Parliament, 1st session (February 2019).

5 The story of his struggle was described in an article in The Indian Voice when he died in 1980. More recently, articles about Patrick and other local First Nations veterans appeared in the Omineca Express (2006) and the Prince George Citizen (2015). These articles and Eric Jameson’s 2016 book The Native Voice were important sources for this story.

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Steve McCullough and Jason Permanand. “Dick Patrick: An Indigenous veteran’s fight for inclusion.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published January 13, 2020. Updated: October 31, 2023. https://humanrights.ca/story/dick-patrick-indigenous-veterans-fight-inclusion