Every person deserves a home, but one’s home should not come at the expense of someone else being forcibly removed from theirs. It gets harder every year for me to accept the reality that as settlers[1] become more settled and comfortable in my land, part of my home and my connection to it becomes erased. Part of me becomes erased.

“My future children will never get to experience the home I knew”

The intergenerational effects of displacement

By Damhat Zagros

Published: June 19, 2024

Tags:

Story text

What makes home, home?

Do you call a place home because you were born there? Because of your connection to the land, history, culture? Do you call it home because you see yourself in the faces of those around you? Or is home, “home” because of how you feel when you are there? We all have our reasons to call a place “home,” but once you are forcibly displaced from your land, your connection, your identity – all of those reasons for calling a place home get mixed, blurred and washed with fear and confusion.

If home was your identity, it’s lost. If home was your connection, you’re alone. If home was your comfort, you are in pain.

What is displacement?

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) report released June 12, 2024,[2] at the end of 2023, there were 117,3 million displaced people due to violence, persecution and other human rights abuses. The rate of displaced people has tripled since 2012 with 1.5% of the world’s population forcibly removed from their home. This is one out of every 69 people on the planet.

The majority of these people are internally displaced persons (IDPs), people who have been forced to leave their home but remain within the borders of their country. IDPs seek refuge wherever they can find it – nearby towns, neighbourhoods, displacement camps and even the wilderness – and are most often spurred to flee as a result of internal conflict or environmental crises. IDPs, as opposed to refugees, are not covered by international law and therefore lack many avenues of assistance (UNHCR, n.d.).

According to the 1951 Refugee Convention,[3] a refugee is defined as anyone forced to flee their home country due to “…a well‐founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a political social group or political opinion.” The number of refugees has steadily increased over the last decade.

While the United Nations, the International Organization for Migration, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre and the international non‐government organization Save the Children all note that the amount of displaced people around the world is dramatically increasing,[4] scholars and those working on the ground are quick to point out that the conditions in which people are living is steadily deteriorating[5] and consequentially – and perhaps most importantly – the intergenerational effects of displacement are breeding grounds for despair, dependency and at times, radicalism.

Forced displacement

War and violence are prime catalysts for forced displacement.

Traditionally, wars were fought between two or more states – a reality which informed the basis for contemporary refugee law. But as wars are increasingly being fought between states and non‐governmental entities – often ununiformed and without clear distinctions between combatants and noncombatants[6] – civilians pay the heaviest price. Borne out of this, too, is the practice of what Greenhill refers to as “coercive engineered migration,”[7] whereby the forced migration of certain populations becomes a deliberate military, diplomatic and financial goal.[8]

Forced displacement is not new. It is both a tool and a consequence of war and colonialism. Since antiquity, the strategic relocation of ethnic groups by peoples in power has been a strategy to conquer lands and dispossess populations. This can be seen here in Turtle Island with the forced relocation of the Cherokee from modern‐day North Carolina and the Inuit in Resolute Bay, as well as current and ongoing examples, including Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank, the ethnic Tibetans and Uyghurs in China, and Kurds throughout Northern Syria, South‐Eastern Turkey and Western Iran, just to name a few situations around the world.

If home was your identity, it’s lost. If home was your connection, you’re alone. If home was your comfort, you are in pain.

Trauma and displacement

People who experience displacement are vulnerable and likely to experience the phenomenon as a form of trauma – the feelings of loss, shame, social and cultural dislocation, and violence. Left unchecked, this trauma can mutate into intergenerational trauma, trauma that continues to be transmitted across generations.

The widespread consequences of intergenerational trauma are myriad, affecting individuals, especially children who are uniquely vulnerable, as well as entire families, communities and even nations.

Losing one’s sense of belonging, cultural assimilation and/or cultural self‐hatred, including the loss of language, history, norms and spirituality, physical, sexual and emotional abuse, severed connections to family members, loss of self‐determination, lack of social integration into new societies, facing prejudices and feeling like an outsider, and so forth, are all consequences of intergenerational trauma.[9]

Who am I and where is home?

Being displaced becomes harder every year. I am Kurdish from Afrin, a Kurdish city in Western Kurdistan located in what is known today as North‐Eastern Syria.

The Kurds are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Mesopotamian plains and mountains of what is now South‐Eastern Turkey, North‐Eastern Syria, Northern Iraq, North‐Western Iran and South‐Western Armenia.[10]

In the early 20th century, many Kurds began to advocate for the establishment of their own country known as “Kurdistan.” Following World War I and the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Western powers promised a Kurdish state through the 1920 Treaty of Sevres.[11] However, the colonial powers reneged on this agreement and to this day, Kurds remain subjugated in their own land and viewed as a threat to, and by, the state governments. Kurdistan continues to remain internationally unrecognized. This is particularly pronounced in Syria where I was born and raised until I fled when I was 17 years old.

The non‐Arab Kurds were perceived as a threat to Syria. To remedy the threat, non‐Arab Kurds were subjected to forcible relocation across the Turkish border, with the government then transferring Syrian Arabs into Kurdish areas. For decades, the Syrian government practiced strategic subjugation of the Kurdish people and identity including, but not limited to: denying formal education, limiting work opportunities, banning cultural gatherings, replacing Kurdish names of public places with Arabic names and building new settlements and villages in Kurdish areas for non‐Kurds. This process is called “Arabization” and was also practiced in Iraq under Saddam Hussein’s regime.[12]

My home, Afrin

My mom tells me I was born during the olive harvesting season. My family had an olive farm in Afrin. My four brothers and one sister would help our family with picking the olives. The whole village would work together like a bee colony. Even though we woke up before dawn every morning to work on the farm, we never felt tired as we worked together. We had one another, we were a community. It is still home.

Our house was built by my father and my grandmother. There was a large living room where our family spent a lot of our time. I was two years old when my father passed away and I never had a chance to meet my grandmother. To me, that house was a piece of them. It holds their smell, spirit and memories. As a child, my mother would walk through each corner of the house telling stories of my father and my grandmother. My grandmother’s handprint was above the front entrance with the date the house was built. That house holds my family’s history. It is a part of us. It is home.

With the start of Syrian Civil War, my mother, two brothers, sister and myself left for Lebanon as refugees. I was 17. I spent the next six years unable to go to school and living precariously due to my refugee status. In 2017, we resettled in Winnipeg as Government Assisted Refugees.

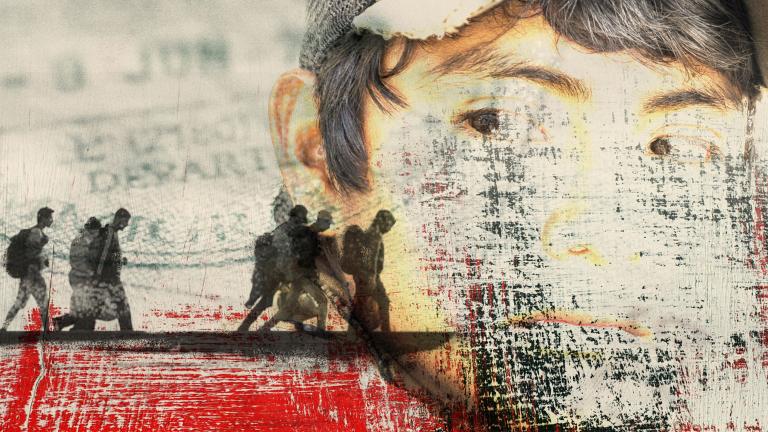

In the winter of 2018, Turkey led what was called Operation Olive Branch with the radical Syrian opposition militia in Afrin to get rid of the Kurdish forces that Turkey viewed as a threat to its security. The eight‐week operation resulted in 690 civilian deaths and the forced displacement of over 300,000 people, the majority of which were Kurds, from their homes.

When we first left Syria, our extended family moved into our family home in Afrin and lived there until Operation Olive Branch. The Syrian opposition group took control of Afrin and forcibly removed my relatives from my family home. Many of my extended family members lost their lives during the operation.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) report released June 12, 2024, at the end of 2023, there were 117,3 million displaced people due to violence, persecution and other human rights abuses.

I was already in Canada when Operation Olive Branch took place. I gathered with other Kurdish community members in the basement of a friend’s house in Winnipeg. We sat in silence and disbelief as we received messages from our loved ones that the city had fallen to the opposition. Being thousands of kilometres away made us feel useless. We were broken. Our homes would never be the same.

After my extended family was removed from my family home, Syrian opposition soldiers and their families moved into our home and changed it completely. The walls with my family’s stories embedded in them have been knocked down. My grandmother's handprint is gone. My childhood castle is now used as a storage shed by strangers. My future children will never get to experience the home I knew.

Things are changing so fast. I feel like I am running out of time. The people are gone, and when the people are gone, there is a risk that the stories will go too.

I am considered one of the “lucky ones.” In 2017, after living as a refugee in Lebanon, I was resettled to a safe third country. I am now a Canadian citizen, studying human rights at a Canadian university. While I am a homeowner, I am not sure if I am home. I am impacted daily by the forced displacement of my own community. Strangers have taken my home from myself, my parents, my siblings and my future children.

During my childhood, I witnessed decolonization efforts within my own community, but I did not have the words or concepts to recognize this as “decolonization.” Since being in Canada, I have learned a lot from Indigenous peoples, their histories, cultures and resistance. Their teachings have helped me to make sense of my own community’s experience of colonization and decolonization which, as a child in Syria, I was too young to understand.

I feel I now have a responsibility to act to decolonize the place I still call home. The best way I know how to do this is through the next generation – the children and youth who may only have fleeting memories of where they, or their parents, are from – to ensure they know their roots, and that no matter where they are, they are always connected to home. But, as Amin Maalouf so clearly points out in his book, In the Name of Identity, one can have multiple homes, and that does not mean one is betraying their roots.[13]

My experiences motivate me to share stories of my home to ensure my connection to home is never lost. I want to share and celebrate our ways of life, traditions, culture and history with future generations. I want to challenge this legacy of colonization. While my community has not been able to fully be themselves, we keep our language and refuse to go to Syrian‐run schools that try to assimilate us. We hold Newroz celebrations to demand our rights and celebrate our culture, and we continue to protest and to hope.

Empowering our children to know who they are and maintain or reclaim their culture is paramount. I contribute to this by writing children’s books that speak about our culture. Through passing on my family and community teachings, I continue to resist and to nurture my home for the next generation.

Video: Conversations about home at the deportation centre by Warsan Shire

This poem, “Conversations about home at the deportation centre,” was written and performed by Warsan Shire, a British‐Somali poet and artist in reaction to the growing worldwide anti‐refugee sentiment.

Ask yourself:

What do you call home? Do you have multiple homes?

What would happen to you if your home was taken from you by force?

Who do you become if your home was taken from you by force?

Explore further

Feature resource guide: Forced Displacement

In this guide, you will find resources about forced displacement worldwide.

Tags:

References

- I use both “settler” and “colonizer” interchangeably, with the recognition that some people willingly participated in the forced displacement of Kurds, while others were displaced themselves. Back to citation 1

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Global Trends, June 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends Back to citation 2

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). https://www.unhcr.org/about-unhcr/who-we-are/1951-refugee-convention Back to citation 3

- Simeon, J. C. (2023). “The Use and Abuse of Forced Migration and Displacement as a Weapon of War.” Frontiers in Human Dynamics, Vol. 5. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fhumd.2023.1172954/full; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2023). Mid‐year trends. https://www.unhcr.org/mid-year-trends#:~:text=At%20the%20end%20of%20June,events%20seriously%20disturbing%20public%20order; Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. 2023 Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID). Back to citation 4

- Phillips, Jason (2023). “Navigating the Ethical Challenges of Work with Detained Migrants and Asylum Seekers in Greece” in Shayna Plaut et al., Messy Ethics in Human Rights Work. UBC Press, Vancouver, Canada, pp 74–92. Back to citation 5

- Kaldor, M. (2005). “Old wars, cold wars, new wars, and the war on terror.” International Politics. Vol. 42, pp. 491–8. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/palgrave.ip.8800126 Back to citation 6

- Greenhill, K. M. (2010). “Weapons of Mass Migration: Forced Displacement as an Instrument of Coercion.” Strategic Insights, v. 9, issue 1 (Spring‐Summer 2010). Back to citation 7

- Simeon, J. C. (2023). “The Use and Abuse of Forced Migration and Displacement as a Weapon of War.” Frontiers in Human Dynamics, Vol. 5. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fhumd.2023.1172954/full Back to citation 8

- Hoosain, S. (2013). The transmission of intergenerational trauma in displaced families. University of the Western Cape. https://etd.uwc.ac.za/handle/11394/3572 Back to citation 9

- BBC. (2019, October 15). “Who are the Kurds?.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-29702440 Back to citation 10

- Radpey, Loqman. (2020) “The Sèvres Centennial: Self‐Determination and the Kurds. Insights, Vol. 24, issue 20, August 10, 2020. https://www.asil.org/insights/volume/24/issue/20/sevres-centennial-self-determination-and-kurds Back to citation 11

- A similar process takes place in Turkey where ethnic Turks are either forced, coerced, or enticed to move into Kurdish‐dominant areas. Back to citation 12

- Maalouf, A. (2001). In the name of identity: Violence and the need to belong. Arcade Publishing. Back to citation 13

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Damhat Zagros. ““My future children will never get to experience the home I knew”.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published June 19, 2024. https://humanrights.ca/story/my-future-children-will-never-get-experience-home-i-knew