During the Second World War, Japanese Canadians were labelled enemy aliens, forced to leave the West Coast for internment camps or farms, and dispossessed of their homes and businesses. This story documents the experiences of the Yamadas and Nishiharas during that tumultuous time.

Shikata Ga Nai / It Can’t Be Helped

The Second World War Experiences of Two Japanese Canadian Families

By Travis Tomchuk

Published: November 14, 2025

Tags:

Photo supplied by Patrice Yamada

Story text

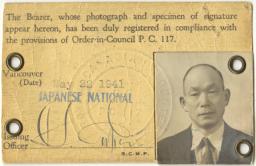

Japan’s December 1941 attack on the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii had a devastating impact on Japanese Canadians living on Canada’s West Coast. Decades of racial animosity towards all Asians living in British Columbia were combined with fears that Japanese Canadians who lived in Canada could act as a fifth column for Imperial Japan’s military ambitions. The Canadian response to the attack was immediate: war was declared on Japan and Japanese Canadians were labelled as “enemy aliens,” [1] which meant their legal and civil rights were suspended. In early 1942, the Canadian government invoked the War Measures Act to force Japanese Canadians to leave the West Coast and gave them two options for relocation: a remote internment camp in the British Columbia interior or moving farther east to farm on the Prairies. Regardless, each person was limited to one suitcase with a maximum weight of 150 lbs for adults or 75 lbs for children. Following this forced relocation, Japanese Canadians left their businesses, homes, vehicles and personal items in the care of the Custodian of Enemy Property, an office created under the War Measures Act [2] to administer the assets of “enemy” populations within Canada. There were assurances that everything would be kept safe for the duration of the war. However, vacated homes could be looted by neighbours and what wasn’t stolen was eventually sold or auctioned by the Custodian well below market value, with Japanese Canadians receiving little in the way of compensation.

The Yamada Family

Patrice Yamada’s family lived through this turmoil. Though she was born in Winnipeg after the war, Patrice’s conversations with family members and research through the Landscapes of Injustice database have allowed her to better understand her family’s history during this period.

Patrice’s parents, Nobuo Yamada and Kiyo Nishihara, came from very different backgrounds. Nobuo lived and worked on a farm in Pitt Meadows, BC, with his family. Kiyo, who planned on attending nursing school, lived with her family in the Powell Street area of Vancouver, a largely Japanese Canadian neighbourhood. The young couple were set up by a community matchmaker and met for the first time on December 7, 1941 – the same day that Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. This event would lead to drastic changes in the lives of the Yamada and Nishihara families. Both experienced the same state oppression of forced relocation and dispossession, but their paths differed after leaving the West Coast.

Once the order was given to leave the West Coast, families had to decide whether to be interned in the BC interior or head farther east to farm. The Yamadas opted to farm. Prior to the war, Patrice’s paternal grandfather Keizo Yamada had purchased 96 acres of land in Pitt Meadows, BC, from a white settler. There he grew strawberries, tomatoes, rhubarb and other crops such as oats. He also raised chickens and sold eggs as part of the Haney Nokai Farmers’ Association – an all‐Japanese Canadian cooperative. Keizo’s wife Shigeno had passed away in 1933, but he had help working the land from his Canadian‐born adult children Toshiko, Fumio and Patrice’s father Nobuo.

With the Yamadas’ agricultural experience, resettlement on a farm seemed like the best option. It also meant that the men and women wouldn’t be separated and could stay together as a family. This was not the case in the internment camps where men between 18 and 45 were forced into hard labour at separate road camps. [3]

In light of events, Patrice’s parents Nobuo and Kiyo decided to get married in a civil ceremony on March 29, 1942. As the newest Yamada, Kiyo was able to travel east with her in‐laws. The Yamadas prepared for their train trip to Manitoba and arrived nearly three weeks later. One of the few items that Kiyo brought to Manitoba was a wedding gift she received from a close friend. For Patrice, the significance of this gift was not evident until much later.

Video: The Wedding Gift

Patrice Yamada recalls the significance of a household item. Video: Annie Kierans, CMHR

Life in Manitoba

When the Yamadas and other Japanese Canadian families arrived in Winnipeg, they were met by farmers who had officially registered [4] to take them on as cheap labour. The Yamadas – all fit adults with a great deal of agricultural experience – were selected by the Erbs who had a sugar beet farm in Oak Bluff, Manitoba.

The Erbs had constructed a small uninsulated wooden shack with a wood stove for the Yamadas – Keizo, Nobuo and Kiyo, Toshiko and husband Matsuji Shinyei, and Fumio. The prairie landscape was quite different to what the Yamadas were used to while living in BC. But the difference for Kiyo was most profound; she went from living with her affluent family in Vancouver to a crowded wooden shack with in‐laws she barely knew. At the same time, Kiyo was dealing with the sadness and loneliness of being separated from her own family in BC.

It took some time for the Yamadas and the Erbs to trust one another. According to Patrice, her family didn’t know what to expect from the Erbs. And the Erbs believed the anti‐Japanese propaganda spread in Canada during the war. However, the Erbs had signed an agreement and they needed the labour to help harvest sugar beets.

Sugar beet farming was hard work and Patrice said her mother Kiyo found it particularly difficult.

“My mom, being a city slicker, was pulling out sugar beets and leaving the dandelions behind. So, she was ill‐prepared to do that hard labour. And she really never did any hard work in her life. So it was up to my aunt. My aunt was a very different personality, and I think she was pretty hard on my mom, by the sounds of it, because she had the skills and my mother wasn’t skillful at all. My grandfather though, he was very kind to her, always had a special place in his heart for my mom. He took her aside and said, ‘Kiyo, this to pull, that to leave in,’ and off she went. But it was a combined effort – everybody had to hit the pavement running, get in the fields. And sugar beets are not easy to nurture and to farm. So, it was a very hands‐on, on your knees tending to that crop, to make sure it got to harvest.”

When asked about freedom of movement, Patrice said that her family was not allowed to leave the Erb farm for their first year in Manitoba due to the conditions of their “enemy alien” designation and forced relocation. During that time, a mutual respect developed between both families. The Yamadas’ reliability and work ethic endeared them to the Erbs. Nobuo, in particular, had proved himself to his host family and, due to his truck driving experience working for the Yamada family farm in BC, was granted special permission by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to leave the Erb farm to drive a transport truck. Nobuo would travel to and from Winnipeg, making deliveries of sugar beets, eggs, lumber and any other items produced on the farm. Kiyo became close with the Erb women who did not work in the fields but ran the homestead and did the cooking. This is how Kiyo learned canning, which she continued to do well after the war. She was also a bit of a seamstress, so she worked with the Erb women to make and mend clothing. During holidays such as Christmas and Easter, the Yamadas and the Erbs would have dinner together.

Patrice describes the Erbs as “wonderful people” who shared what they had with the Yamadas. Both families became close and maintained their friendship far beyond the Second World War. Her older sister and brother, who played with the Erb children, maintained those relationships throughout their lives. Patrice is thankful that the Erbs were kind to and supportive of her family at a time of great trauma, as this wasn’t always the case for Japanese Canadians who farmed on the Prairies. Mickey Nakashima, who was relocated to an Alberta sugar beet farm with her family, told how children were expected to work the crops.

“The hardest part [of the harvest] was the beet topping in the fall with knives that were too large for our small hands. My mother wrapped rags around the little wrists of my younger siblings to help lift the heavy beets and knock off the clumps of soil before the heads were topped and tossed onto the truck.” [5]

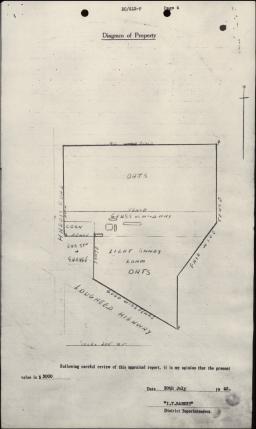

The Yamadas spent three years at the Erb farm. During that time, Patrice’s grandfather Keizo leased the 96 acres he owned in Pitt Meadows, BC, to the town’s reeve, who promised to oversee the land, the house and the farming implements until Keizo returned. Believing this elected official could be trusted, Keizo didn’t bother registering the land and its contents with the Office of the Custodian of Enemy Property. Within a year, the land he had bought for $14,976.00 had been sold and Keizo received nothing in compensation. After the war, he testified at the Bird Commission. As part of this process, and because he had not registered his farm and included assets with the Custodian, Keizo provided a list of everything he left behind along with their monetary value. In the end, however, he was awarded a meagre $336.94 for the assets that had been sold out from under him. The property along the Lougheed Highway in Pitt Meadows has since become valuable commercial real estate.

The Nishihara Family

The Nishiharas lost their Vancouver home during the war. Prior to the forced relocation, Patrice’s mother Kiyo Nishihara lived with her father Yasushi, brother Nagayoshi and sister Sachi, Yasushi’s second wife Aiko Fujimagari, [6] and her two children Sakae and James. Yasushi worked for James Fyfe Smith, the owner of a hardwood lumber company, and was an important figure in Vancouver’s Japanese Canadian community. He acted as an intermediary between Japanese Canadians and the majority white population in the city. His opinion was also sought by fellow Japanese Canadians regarding issues within the community.

The Nishiharas, not having a background in agriculture, were forced to move to Tashme, the site of a former relief work camp during the Depression. This site, opened in September 1942, had very basic accommodations. Housing consisted of simple, uninsulated wooden shacks that lacked indoor plumbing and were heated by a single wood stove – a stark contrast to the modern homes that most of those forced to relocate had left behind. Patrice’s uncle Nagayoshi, however, did not reside in Tashme with his wife Fumiko and daughter Misae. Being a physically fit male between the ages of 18 and 45 meant Nagoyoshi was forced to work at the Blue River road camp, likely constructing the Hope‐Princeton Highway. [7] With husbands away at road camps, women were left to look after their children alone if they did not have an older parent in camp to help.

For those Japanese Canadians relocated to internment camps or road camps, the new realities of life and an uncertain future created great stress. Lives had been completely altered by government decree. Internees had been cut off from friends and families and lost homes and livelihoods. They did not know how long they would be in camps. Radios and newspapers were banned in internment camps, so Japanese Canadians were effectively cut off from the wider world. [8]

The Intergenerational Effects of Forced Relocation and Internment

After the war, as Japanese Canadians were released from farm labour and the internment camps closed, they had to start over from scratch as they often had no homes to return to. Keizo bought land in Vermette, Manitoba, and resumed farming. Nobuo and Fumio established Yamada Construction but were unable to make a long‐term career from the business. Nobuo, however, went on to work for a multinational construction firm that took him to work sites all over the world. Kiyo was unable to realize her dream of being a nurse, but she was still able to find work in healthcare, first as a healthcare aide and then as a medical receptionist. The wartime experiences of the Yamadas had a lasting influence. Though the family still met with other Japanese Canadian community members on occasion, they chose to live among Canadians from other backgrounds. The Yamadas kept their heads down, worked hard and assimilated as best they could.

Patrice felt that her parents didn’t want to be visible and only wished to fit into the broader Canadian society. They didn’t want to be ostracized or racialized or give any “reason” to be discriminated against. For the Yamadas, they wanted to just work hard, prosper, and “get on with life,” because everything else that had happened in the past was shikata ga nai. [9]

The family went so far as to consciously choose to attend a hakujin [10] church, which spoke volumes to Patrice, recognizing this as part of her family’s efforts to be included as much as possible, and not “stick out” as a visible minority.

On the Nishihara side, Patrice’s maternal grandfather Yasushi returned to the lumber trade in British Columbia. Her uncle Nagayoshi, much like her father and uncle Fumio, went into construction. Aunt Sachi moved to Winnipeg to be closer to Kiyo and got a job sewing gloves at Western Glove Works. Aunt Sakae married after the war and moved to Ontario. Uncle James stayed in BC, joined the Canadian Armed Forces and married.

According to Patrice, the majority of her family looked back at what happened as shigata ga nai and wanted to focus on moving forward with their lives and rebuilding what they had.

Video: Starting Over

Patrice Yamada explains that for her parents starting over after the war was the only alternative. Video: Annie Kierans, CMHR

Uncle Nagayoshi

But her uncle Nagayoshi was an outlier. The anger and resentment he felt over the injustice he experienced, particularly losing his social standing as a mover and shaker in Vancouver, never left him.

Video: Uncle Nagayoshi

Patrice Yamada explains the anger and resentment her uncle Nagayoshi felt because of his treatment during the Second World War. Video: Annie Kierans, CMHR

Redress and Beyond

In 1988, after more than a decade of lobbying the federal government, Japanese Canadians were successful in receiving a formal apology in the House of Commons and financial compensation. Each Japanese Canadian who was affected by internment and forced relocation was paid $21,000 for their loss of property and personal anguish. Patrice’s family had mixed feelings about the compensation. Some were grateful while others felt guilty about accepting this money even after what they had been put through. Her mother Kiyo took issue with her stepbrother James for using his compensation to buy an expensive car. For Kiyo, this went against the spirit of redress.

The mass removal of Japanese Canadians from BC’s West Coast resulted in a great deal of fear, stress and hardship. Families who had spent decades building successful enterprises and establishing themselves had everything taken away within a matter of months following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and Canada’s declaration of war against that country. This dispossession has had lasting effects on successive generations of Japanese Canadians: neighbourhoods that existed before the war had changed, strangers now lived in family homes, property that became extremely valuable had been sold without owner input or recompense. Japanese Canadians also had to come to terms with their own government turning on them and taking away everything they had. But a successful redress campaign did not mean the story was closed. As those Japanese Canadians who were directly affected by internment and forced removal pass on, many projects have been created and continued to be planned to keep this important history alive and build upon it.

Such a project is Landscapes of Injustice, mentioned above. Researchers and community members spent seven years researching the lived experiences of affected Japanese Canadians, conducting oral histories and pouring over archival documents to understand both what was taken and what this meant for the Japanese Canadian community. This resulted in a large database of government records and personal correspondence that led to two publications: Landscapes of Injustice: A New Perspective on the Internment and Dispossession of Japanese Canadians and Witness to Loss: Race, Culpability, and Memory in the Dispossession of Japanese Canadians . Another project output was the Broken Promises exhibition now open at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights until late April 2026. These project outcomes have focused on the little‐known history of the dispossession of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War in order to share this history with Canadians.

For Patrice Yamada, sharing her family’s story is important for two reasons. As she explains,

“I come to this point in time as a Sansei, that is, a third‐generation Japanese Canadian. Recently, I was participating in a teaching given by a Cree Elder who talked a lot about generations. Because I am Sansei, I was born after the end of the Second World War, and I really wasn’t directly involved in all the tumultuous events that occurred during that time with Japanese Canadians. But what the Elder taught me was that I’m at sort of the middle point of seven generations: three before me and three that will follow me. So, I want to really honour the experience of my ancestors, my relatives. But also, to provide respect and peace for those that follow after. I’m at the middle of all of that conversation and I’m hoping I can represent what really happened in a Sansei kind of way.”

Ask yourself

Can you imagine your own government turning on you and forcing you from your home?

Why do you think the Canadian government has resorted to internment in times of war?

Who would have gained from the dispossession of Japanese Canadians?

References

- The enemy alien designation meant all Japanese Canadians were labelled enemy aliens regardless of whether they were Japanese nationals, naturalized Canadians, or Canadian born. The overwhelming majority were Canadian citizens. Back to citation 1

- The War Measures Act gave the Canadian government sweeping powers during times of war. It allowed for the internment of civilian populations, suppression of the press and arrest without charge. Back to citation 2

- “Employment,” Tashme Historical Project. Back to citation 3

- The Sugar Beet Program was created by the British Columbia Security Commission to help pair farmers with Japanese Canadians willing to relocated east of the Rockies. This program was announced in late March 1942. Shelley D Ketchell, “Re‐locating Japanese Canadian History: Sugar Beet Farms as Carceral Sites in Alberta and Manitoba, February 1942‐January 1943” MA Thesis, University of British Columbia, 2005, 6. Back to citation 4

- Pamela Hickman and Masako Fukawa, Japanese Canadian Internment during the Second World War (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 2011) 119. Back to citation 5

- Kiyo’s mother Shigeno had passed away prior to the war and her father married Aiko in 1939. Back to citation 6

- Nagayoshi’s father Yasushi was 49 at this time so was not required to work at a road camp. Back to citation 7

- “Life in a Japanese Canadian Internment Camp, 1942–1946,” Tashme Historical Project Back to citation 8

- Shikata ga nai means “it cannot be helped.” Back to citation 9

- Hakujin means “white person.” Back to citation 10

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Travis Tomchuk. “Shikata Ga Nai / It Can’t Be Helped.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published November 14, 2025. https://humanrights.ca/story/shikata-ga-nai-it-cant-be-helped