The distortion of facts doesn’t just blur the truth — it shapes how the world sees a conflict, downplaying real suffering and making it easier to see others as “the enemy.” Disinformation is a direct threat to human rights. We see examples of this weapon of war taking a toll in conflicts today.

Information Disorder in Times of Conflict

The role of disinformation and misinformation in shaping conflict

By Saranaz Barforoush, Ph. D. and Shayna Plaut, Ph. D.

Published: January 15, 2025

Tags:

Photo: Mstyslav Chernov, The Canadian Press

Story text

In 2023, Israeli forces besieged Al‐Shifa Hospital, the largest medical complex and central hospital in the Gaza Strip. Israel cited intelligence that Hamas — the group in Palestine who claimed responsibility for the brutal and deadly October 7 attacks in Israel — was using the hospital as a covert base: a place to plot, store weapons and prepare for more violence. Hamas vehemently denied this. After 14 days of fighting, a multi‐agency mission led by the World Health Organization (WHO) accessed Al‐Shifa and said it was “now an empty shell.”[1] WHO and many news outlets reported[2] that at least 20 patients had died, according to the Hamas‐run Gaza Ministry of Health.

The Israel Defense Forces’ destruction of Al‐Shifa Hospital continues to raise questions about responsibilities under the laws of war, the uses and misuses of medical facilities and the role that media plays in creating, and perpetuating, different narratives.

In the midst of the fighting, radically different stories about the siege spread on social media, the viral shock amplified by images, videos and first‐hand testimonies of combatants, doctors and patients (including critically ill adults and children), as well as Israeli and Hamas government officials. As fighting raged through Al-Shifa’s wards and hallways, the world outside witnessed and passed judgement on the competing narratives. Facts, already complex, became suspect. Soon, disinformation campaigns became one more weapon creating only two opposing sides of a story.

The Times of Israel[3], among other Israeli media outlets, reported the Israeli government’s claim that there was “concrete proof” of a Hamas‐run command centre in Al‐Shifa, which could be accessed by hospital staff, therefore justifying the attack on a civilian hospital. Outlets such as The Washington Post[4] confirmed that, although there were tunnels underneath the hospital and that United States and Israeli intelligence believed that Hamas used the area as a command centre, it was not clear as to when the tunnels were in use. In addition, it is doubtful hospital staff had any access to these tunnels. Hotly contested narratives about the legitimacy of the attack on Al‐Shifa Hospital continue to swirl. As such, both sides are accused of violating the laws of armed conflict and international humanitarian law.

Similarly, during the earlier days of the conflict, a viral video supposedly showed Hamas militants throwing individuals off a rooftop. Investigations by news outlets such[5] as AFP revealed the footage was fake — it was a 2015 clip from Iraq, not Palestine.

Both sides are using media in their arsenal. Hamas‐backed media consistently deny the murder of Israeli civilians on October 7, falsely claiming that all those killed or kidnapped were Israeli military and thus “legitimate” targets. And in March 2024, Al Jazeera had to retract a video where a woman accused Israeli soldiers of sexual assault — a claim that both Hamas investigators and the network itself discredited. Such misrepresentations contribute to a growing crisis of credibility in the media and have resulted in record‐high levels of distrust in journalism worldwide.

The media toolbox – what’s said and what is absent tells a story

Our news and explorer feeds do not reflect what is actually happening in the world, but rather what is deemed important to those producing, sharing, liking and commenting on the content. Social media, for all its democratic promise, has exposed how easily misinformation and disinformation can be amplified to mislead us.

The “platformization” of news[6] and our dependency on algorithms that curate news feeds have pushed us into “echo chambers,” where we rarely hear alternative (and often truer) narratives.

What’s not covered in the news can tell a story as important as what is. According to the Geneva Academy, there are hundreds of conflicts raging in the world right now that are sporadically covered, if at all, because they are not deemed “important.” Currently, in Canada, the wars getting the most airtime and political attention are those in Ukraine/Russia and Gaza/Israel.

Conflicting narratives and the casualty of truth

These two conflicts are both reaching grim milestones. By the end of 2024, over one million Russians and Ukrainians were killed or injured, 4 million Ukrainians[7] were forced to move to other parts of the country, and 6.8 million Ukrainians[8] have fled Ukraine. Russian citizens have also faced catastrophic consequences — nearly 800,000 Russian civilians[9] have fled, either to other parts of Russia or to other countries. In the Middle East, over 43,000 Palestinians[10] and more than 1,600 Israelis[11] (both combatants and civilians in both cases) have been reported killed, including academics and humanitarian workers[12].

But even the truth of death is not settled fact. Mark Twain (quoting Disraeli) said it best: “There are lies, damned lies and statistics.” The number of casualties in both wars is filtered through a political lens. For instance, both the Hamas‐run Ministry of Health and the Israel Defense Forces report on the number of dead and injured in Gaza — with each side discrediting the other’s numbers.

The strategy is simple and effective: pick up on something small and partially true and generalize it out of context to undermine an entire people and thus erase the sovereignty of an entire country.

Disinformation

The use of disinformation and propaganda in conflict puts civilian rights and safety at risk. A troubling example of the “real world” human rights impact of exaggerated and out‐of‐context falsehoods unfolded in 2022, just days before the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Russian President Vladimir Putin leaned into his country’s deep historical trauma from the Second World War and Nazi aggression, which killed 24 million Soviets (not counting Ukrainians), according to World Population Review[13]. In his speech[14], Putin invoked narratives of “protection” and “security” — speaking of a supposed “genocide” against Russians.

Putin’s messaging focused on a small yet controversial arm of the Ukrainian military known as the Azov Battalion. Azov is reported to have neo‐Nazi ties and far‐right tendencies. He framed the invasion as a mission to “demilitarize and de‐Nazify” Ukraine. The sweeping nature of Russia’s accusations seemed ironic to the international community since Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the Ukrainian president, is from a Jewish family and a descendant of Holocaust survivors. Intense rebuttals were issued by world leaders, journalists and peace activists. The narrative, however, had already entered the public discourse through social media and pro‐Russian news outlets, and “de‐Nazification” was used over and over again to justify the aggression against Ukraine.

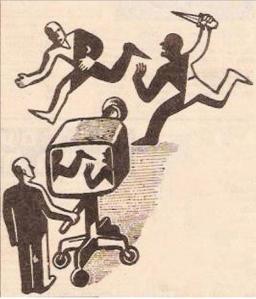

Online space as a deadly weapon of war

Conflicts today aren’t confined to physical borders — they also unfold on our screens, flooding our social media feeds and capturing global attention. Experts call this “information warfare” or “social media warfare.” Platforms including TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Discord, Telegram and X have become battlegrounds where each side seeks to control the narrative using images, videos and posts as weapons. Here, every “like,” “share” and “comment” contributes to shaping public opinion and amplifying the voices of both supporters and critics worldwide. Put simply: disinformation has been weaponized globally.

In the Israel‐Hamas conflict, for instance, disinformation has significantly impacted human rights by silencing legitimate voices, undermining the credibility of victims, endangering humanitarian workers and journalists, justifying indiscriminate attacks, and even influencing policy decisions. As the Bulletin for Atomic Scientists rightly explained, “one of the riskiest aspects of disinformation is that it can make individuals cynical because it plays right into the ill‐intentioned actor’s hands. Such actors can convince people to believe their narrative, and even if they can’t convince, they can … eventually demoralize them. Finally, they will make people feel that even trying to solve a problem is a useless attempt, making individuals apathetic.”

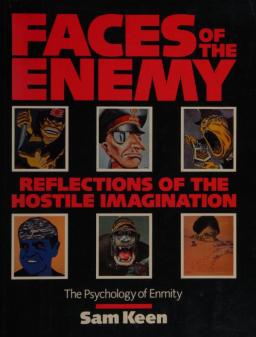

By the time a false narrative is exposed as a lie, the damage is already done. Fear and anxiety — often rooted in history—take hold, and in their wake comes something darker: the creation of an enemy, the ultimate “other.”[15] The hysteria is intensified and “the other” — the threat — needs to be stopped.

“Information disorder” doesn’t just muddy the facts — it primes the emotional powder keg.

In times of conflict, people become scared and feel they must choose sides. History is littered with examples where media and messaging played pivotal roles in atrocities. Court rulings from Nuremberg to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda recognized this, exposing how media are a tool of war transforming groups into “the other,” thus paving the way for dehumanization, oppressive policies and mass violence. In the age of digital megaphones, the stakes are even higher. We are no longer passive audiences — we are part of the media machine. Demagogues, internet trolls and shadowy provocateurs exploit our collective fears, weaponizing misinformation to normalize human rights abuses.

When despair is discredited

In war, even the truth can be branded a lie in the chaos of conflict. One side often works to undermine the pain and suffering of the other, planting seeds of doubt that poison the credibility of future accounts.

In this era of artificial intelligence and deepfakes, even the most harrowing images can be dismissed as fabrications, staged for effect. This weaponizes skepticism, allowing uncomfortable truths to be discredited, ignored or buried.

The crisis in Gaza offers a clear example. As BBC reported[16], Israeli children who witnessed the murder of their parents in front of their eyes were dismissed as “crisis actors” — people pretending to be suffering — and a Palestinian mother who buried her infant son was falsely accused of staging the burial with a doll. Narratives like this significantly intensified when a video purportedly showing a Palestinian man get up from a stretcher and run off was uploaded online and went viral. This created a firestorm of online chatter that spilled into mainstream news outlets, promoting the idea that the devastating scenes in the Al‐Shifa Hospital and in Gaza are staged. Meta (Facebook’s parent company) flagged the video as fake and further investigation by fact‐checking sites showed it was actually filmed in March 2020 and did not take place in Gaza[17]. However, “information disorder” had taken hold and footage coming out of Gaza was deemed suspicious by all sides.

Identifying and countering misinformation

Conflict reporting comes with no shortage of obstacles: restricted access, constant safety risks, unreliable sources, and the relentless pressure of social media narratives. Which can, and does, lead to mistakes. This is misinformation.

The role of news organizations in managing misinformation during conflicts is pivotal and fraught with complexity. Narratives can be heavily politicized and biases — whether originating from the journalist, news organization, government or other sources — deeply entrenched. Another challenge is that journalists who parachute in from abroad often lack linguistic and cultural understanding, at times producing flawed or superficial coverage. Sometimes, errors stem from genuine misunderstanding; other times, journalists are manipulated by local actors eager to promote “their side” of the story.[18]

Yet the best journalists and outlets prioritize rigorous fact‐checking and demonstrate integrity by correcting mistakes when they occur. While errors are sometimes unavoidable, they starkly contrast with the deliberate distortion of facts — a far more insidious threat to the truth.

But not all journalists and news outlets uphold these standards. Russia Today (RT), for example, has a track record of amplifying messages that mirror the Kremlin’s. In 2024, the U.S. State Department accused RT and its parent company, Rossiya Segodnya, of acting as a “de‐facto arm” of Russian intelligence. Former employees of the network reported that RT collaborated with Russian intelligence units to further Moscow’s interests. The investigation also revealed that Canadian influencers[19] promoted pro‐Putin narratives concerning the war in Ukraine.

U.S. President Donald Trump is perhaps the most famous leader to talk about “fake news,” but he didn’t invent the term. Nor is he the first politician to brand the press as the enemy — that long list is growing worldwide. With this kind of rhetoric winning hearts and minds globally, it’s worth reflecting on the consequences of attacking and delegitimizing a free and responsible press. A robust, independent media is vital to ensuring we navigate the world through verified facts — not rumours driven by fear and untrustworthy information.

Journalists remain on the front lines, risking their lives to report from conflict zones. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, by December 2024, over 150 members of the media have been killed since the start of the most recent Israel–Hamas conflict — some of the highest rates of journalistic deaths in any armed conflict over the past 100 years.

Media literacy: our collective responsibility

But here’s the catch: Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights guarantees the right to opinion, expression and information. However, with that freedom comes an equally critical responsibility: to be accountable for the narratives we amplify.

The answer isn’t to restrict free speech in the name of truth, but to recognize that manipulating information — spreading lies to sway opinions and distract from real issues — is a violation of those same rights. Protecting access to accurate information is as essential as protecting the right to share it.

Ask yourself

Which media sources do you trust and why?

How do you check the accuracy of information before sharing?

How do you see the relationship between human rights and information disorder?

Dive Deeper

Misinformation, Disinformation and Malinformation

By Priscila Alves Werton and Stephen Carney

We invite you to explore this guide as a starting point to learning more about misinformation, disinformation and malinformation – the inadvertent or purposeful spread of false information – and their impact on human rights causes.

References

- WHO. “Six months of war leave Al‐Shifa hospital in ruins, WHO mission reports.” World Health Organization, 6 Apr. 2024, https://www.who.int/news/item/06–04-2024-six-months-of-war-leave-al-shifa-hospital-in-ruins–who-mission-reports. Back to citation 1

- Jobain, Najib, Bassem Mroue, and Samy Magdy. “32 babies in critical condition are among the patients left at Gaza’s main hospital, UN team says.” Associated Press, 18 Nov. 2023, https://apnews.com/article/israel-hamas-war-news-11–18-2023–5ffcdeeca3eb3dbcd8af8d207a8e4a4a. Back to citation 2

- Fabian, Emanuel, and TOI Staff. “Hamas’s main operations base is under Shifa Hospital in Gaza City, says IDF.” The Times of Israel, 27 Oct. 2023, https://www.timesofisrael.com/hamass-main-operations-base-is-under-shifa-hospital-in-gaza-city-says-idf/. Back to citation 3

- Loveluck, Louisa, Evan Hill, Jonathan Baran, Jarrett Levy, and Ellen Nakashima. “The case of al‐Shifa: Investigating the assault on Gaza’s largest hospital.” The Washington Post, 21 Dec. 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/12/21/al-shifa-hospital-gaza-hamas-israel/. Back to citation 4

- Roley, Gwen. “Video does not show Hamas throwing people off a roof.” Agence France‐Presse Fact Check, 12 Dec. 2023, https://factcheck.afp.com/doc.afp.com.347B339. Back to citation 5

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis, and Richard Fletcher. “Comparing the Platformization of News Media Systems: A Cross‐Country Analysis.” European Journal of Communication (London), vol. 38, no. 5, 2023, pp. 484–99, https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231231189043. Back to citation 6

- UNHCR. “Ukraine Emergency.” https://www.unrefugees.org/emergencies/ukraine/#:~:text=Emergencies&text=There%20are%20nearly%204%20million,(as%20of%20November%202024).&text=6.8%20million%20refugees%20from%20Ukraine,(as%20of%20November%202024).&text=Approximately%2014.6%20million%20people%20are%20in%20need%20of%20humanitarian%20assistance%20in%202024. Back to citation 7

- UNHCR. “Ukraine Emergency.” https://www.unrefugees.org/emergencies/ukraine/#:~:text=About%20the%20War%20in%20Ukraine&text=As%20a%20result%20of%20heavy,Moldova%20or%20other%20countries%20globally. Back to citation 8

- Matusevich, Yan. “Uncertain Horizons: Russians in Exile.” Mixed Migration Centre, 12 Feb. 2024, https://mixedmigration.org/uncertain-horizons-russians-in-exile/#:~:text=It%20is%20estimated%20that%20over,%2C%20Serbia%2C%20Turkey%20and%20Germany. Back to citation 9

- OCHA. “Reported impact snapshots – Gaza Strip (10 December 2024).” 10 Dec. 2024, https://www.ochaopt.org/content/reported-impact-snapshot-gaza-strip-10-december-2024. Back to citation 10

- U.S. Department of Defense. “Statements by Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III Marking One Year Since Hamas’s October 7th Terrorist Assault on the State of Israel.” 7 Oct. 2024, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/article/3927710/statement-by-secretary-of-defense-lloyd-j-austin-iii-marking-one-year-since-ham/#:~:text=A%20year%20ago%20today%2C%20on,people%20hostage%2C%20including%2012%20Americans. Back to citation 11

- Desai, Chandni. “The war in Gaza is wiping out Palestine’s education and knowledge systems.” The Conversation, 8 Feb. 2024, https://theconversation.com/the-war-in-gaza-is-wiping-out-palestines-education-and-knowledge-systems-222055. Back to citation 12

- World Population Review. “World War II Casualties by Country 2024.” https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/world-war-two-casualties-by-country. Back to citation 13

- Al Jazeera. “‘No other option’: Excerpts of Putin’s speech declaring war.” Al Jazeera, 24 Feb. 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/24/putins-speech-declaring-war-on-ukraine-translated-excerpts. Back to citation 14

- Curle, Clint. “Us vs. Them: The process of othering.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights, 24 Jan. 2020, https://humanrights.ca/story/us-vs-them-process-othering. Back to citation 15

- Robinson, Olga, and Shayan Sardarizadeh. “False claims of staged deaths surge in Israel‐Gaza war.” BBC, 21 Dec. 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-67760523. Back to citation 16

- Reuters. “Fact Check: Video showing body rising from stretcher is not linked to current situation in Gaza.” Reuters, 13 May 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/fact-check/video-showing-body-rising-from-stretcher-is-not-linked-to-current-situation-in-g-idUSL1N2N00RT/. Back to citation 17

- Klein, Peter W., and Shayna Plaut. “‘Fixing’ the Journalist‐Fixer Relationship.” Nieman Report, 15 Nov. 2017, https://niemanreports.org/fixing-the-journalist-fixer-relationship/#:~:text=Our%20research%20study%2C%20“Fixing”,this%20critical%20relationship%20views%20their. Back to citation 18

- RCI. “Meet the right‐wing Canadian influencers accused of collaborating with an alleged Russian propaganda scheme.” RCI, 6 Sep. 2024, https://ici.radio-canada.ca/rci/en/news/2102493/meet-the-right-wing-canadian-influencers-accused-of-collaborating-with-an-alleged-russian-propaganda-scheme. Back to citation 19

Suggested citation

Suggested citation : Saranaz Barforoush, Ph. D. and Shayna Plaut, Ph. D.. “Information Disorder in Times of Conflict.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Published January 15, 2025. https://humanrights.ca/story/information-disorder-times-conflict